The Final ROFLCon and Mobile's Impact on Internet Culture

A little late on this, but wow, ROFLCon III was amazing. I was there to moderate a morning keynote panel on the supercut meme with Rich Juzwiak, Duncan Robson and Aaron Valdez, three of my favorite supercut creators. It was a privilege to share the stage with these guys, who are all amazing at what they do. It ended with a debut of Duncan’s Three Point Landing, which the audience adored. Here’s the whole thing.

Every talk I saw was amazing. All the sessions are making their way onto YouTube, and are all worth checking out. I posted some of my personal highlights on Twitter, but if you missed them, here are my favorites:

Jonathan Zittrain’s introductory keynote was thoughtful and inspiring. Jason Scott’s solo talk on the Mysterious Mr. Hokum is a crazy story of a pre-Internet scammer. Flourish Klink’s panel on fangirl culture was eye-opening, a glimpse into a massive subculture of the web I know far too little about.

The most entertaining, hands down, was Craig Allen’s behind-the-scenes story of the Old Spice campaign, with a surprise Skype cameo by Isiaiah Mustafa.

The most underseen and misunderstood session was Wonder-Tonic’s pitch for Localoffrly.biz, a douchebag startup turned into comedy performance art. (Bonus points for actually launching a site.) Hard to believe, but some people in the audience weren’t sure whether it was a joke, and started to get frustrated when they stopped the gamified talk between each “level.” Brave.

And, of course, Chris Poole’s solo talk, which ended up inspiring my Wired column that was published last Wednesday. I reprinted it below, hope you enjoy it.

Early this month, the Internet invaded the MIT campus for ROFLCon III, the biennial two-day conference that brings together the subjects of net memes with those who study and adore them.

Among the meme celebrities — Tron Guy, Paul “Double Rainbow” Vasquez, Antoine Dodson, Scumbag Steve and Chuck Testa all attended — were those who are deeply invested in the future of Internet culture, both emotionally and financially. Founders of community sites like Reddit and 4chan, academics studying memes, and the cottage industry that’s capitalized on them, most notably the Cheezburger Network’s Ben Huh. And, of course, the whole audience participated in their propogation.

From the moment I boarded the plane to Boston there was an undercurrent of change running through the conference. I sat next to Whitney Phillips, a University of Oregon doctoral student speaking on a panel about her research on troll culture. She’d attended every ROFLCon since 2008, and realized that she’d have to revise her thesis in the next month — the meme landscape is in a transitional period, but it’s not clear what it’s transitioning into. She echoed something I heard repeatedly over the weekend: “It just feels different.”

It felt apropos that this was the last ROFLCon, with the organizers “putting this trilogy to bed and riding out into the sunset.” Or, at least, until “we can figure out how to continue doing it great justice.”

The Internet is still spawning memes at an accelerated rate — and they’ll never go away. But there are some major shifts under way that may fundamentally change the way they’re created.

Every meme, like folklore, shares two common characteristics: It must show reproduction (the ability to be copied) and variation (the ability to mutate).

These days, memes spread faster and wider than ever, with social networks acting as the fuel for mass distribution. But it’s possible we may see less mutation and remixing in the near future. As Internet usage shifts from desktops and laptops to mobile devices and tablets, the ability to mutate memes in a meaningful way becomes harder.

From the Interest Web to the Social Web

Over the last few years, we’ve seen a fundamental shift away from discussion forums and other niche communities to social networks and aggregators. In a 20-minute talk at ROFLCon, 4chan and Canvas founder Chris Poole characterized this as a shift from the interest-based web to the friend-based web.

Poole is concerned that the web is losing its emotional depth, a richness that comes from lurking, failing and learning before finding your place in a community. The difficulty gave it more meaning, and the resulting communities added far more value to the web than they extracted.

Now, aggregators like 9GAG and Cheezburger are ridiculously popular, but memes rarely originate there. Unsourced images are posted and watermarked by their new hosts, muddling their origins and diluting the context of the original image. As Poole said, “It’s hard to feel emotionally invested in 9GAG.”

To me, this is part of the natural expansion of online community. Reddit users hate 9GAG for stealing their memes, but 9GAG is popular because it’s easier to use, making it more inclusive to Facebook users than Reddit’s sprawling subgenres and somewhat esoteric community norms. It’s the same reason that, for years, 4chan users hated Reddit for stealing their memes and bringing them to a community that was much easier to understand.

Unlike social networks, each successive community doesn’t seem to cannibalize its predecessor, but instead simply finds a larger, newer audience. The original community stays largely the same, which feels like stagnation relative to the “next big thing.” With each new site, the mainstream base and shared knowledge we call “Internet culture” converges into a mixed cultural heritage.

But there’s one potential risk that affects the cultural production of memes.

Meme Mutation

Ever tried using 4chan on a iPhone? It’s completely impossible to upload images from an iPhone or iPad, immediately limiting your contribution to the community to commenting alone. Sites like Reddit let you post a URL, but modifying and uploading images to a public URL from a mobile device is, for the moment, not easy.

Also for the moment, it’s extremely rare for mobile apps to allow community remix and sharing. In fact, I could only find two iOS apps that supported posting your own remixes to a public community space: Mixel and Make Pixel Art. (If you know more, leave them in the comments.) All others only support sharing to your contacts or your own social network, but not the public, unmediated space that memes thrive in.

It’s not surprising, then, that the only memes that seem to originate on smartphones are text-based — autocorrect fail, iPhone whale, and texts from last night.

It feels like we’re on the verge of a breakthrough to unleash the creative potential of these devices, but mobile developers are limiting our options to mild tweaking, at best. Instagram’s filters made the simplest cosmetic changes, and you weren’t able to modify anybody else’s work. Draw Something let you draw, but only with a single person and no shared history. Where’s the Canvas, Polyvore, deviantArt, and YTMND of the app world?

In the absence of good remix apps, image macro generators like Meme Generator and Quick Meme have filled the gap, making it possible to instantly generate a new meme from a mobile browser in seconds. No tools, or time investment, required.

This is incredibly empowering, but also limiting. Your imagination, and the scope of the meme’s breadth, is limited to the capabilities of the meme generator.

It’s reasonable to think the shift from desktops and laptops to mobile and tablets will continue, especially for the new generations of young Internet users that typically generate memes. If the app ecosystem doesn’t grow to accommodate it, we may see remix participation drop, largely substituted by the lightweight interaction of likes, favs and comments and lightweight prebuilt memes from generators.

In his talk on Saturday, Poole said, “Memes are the instruments with which we play music. The way things are going, we’re going to lose our song.”

Memes may not go away, but I’m worried we may lose the concert venues where the music is performed — the quirky, difficult communities that foster creative expression and make it meaningful.

Criminal Creativity: Untangling Cover Song Licensing on YouTube

We all break laws. Every day, millions of people jaywalk, download music, and drive above the speed limit. Some laws are obscure, others are inconvenient, and others are just fun to break.

There are millions of cover songs on YouTube, with around 12,000 new covers uploaded in the last 24 hours. Nearly 40,000 people covered “Rolling in the Deep,” 11,000 took on “Pumped Up Kicks,” 6,000 were inspired by “Somebody That I Used to Know.”

Until recently, all but a sliver were illegal, considered infringement under current copyright law. Nearly all were non-commercial, created out of love by fans of the source material, with no negative impact on the market value of the original.

This is creativity criminalized, quite possibly the most popular creative act that’s against the law.

I don’t think it’s an act of civil disobedience; nobody’s making a statement. Most people don’t know that cover songs need a synchronization license, and even if they did, trying to get one is a confusing and expensive proposition. Unlike the mechanical licenses used to release a cover song on an album, video sync licenses don’t have an affordable flat rate and require the publisher’s explicit permission.

Even as YouTube forges agreements with publishers to handle the synchronization rights for cover songs, it’s nearly impossible for musicians to tell whether their songs are covered or not.

This week, I set out to answer a seemingly simple question: when are YouTube cover songs legal, and how can we do this better?

Conflicting Information

Even trying to determine if a cover song is legal can be confusing for most musicians. There’s no shortage of answers online, but most of them are conflicting. Publishers, musicians, and lawyers all give different answers, none of which are totally accurate. Even YouTube’s own FAQs are incomplete, made inaccurate by recent settlement agreements.

Like any area of copyright law, there’s no shortage of armchair lawyering on blogs and discussion forums about cover songs. A common belief is that cover songs fall under the “fair use” provisions of the Copyright Act, but the question of whether a non-parody cover song could fall under fair use is untested in the courts. Despite this, over 60,000 cover songs on YouTube cite “fair use” in their title or description. (Whether uploaders actually believe that or are preemptively using it as a defense is anyone’s guess.)

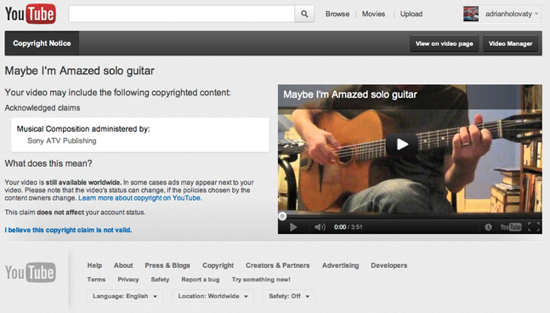

Content ID detects one of Adrian Holovaty’s cover song

While they happily encourage fans to upload covers, YouTube makes it clear that users must have the rights to all content they upload. “We tell users they must own the copyright or have the necessary rights for any content they upload,” said a YouTube representative. “It’s ultimately their responsibility to know whether they possess the rights for a particular piece of content.”

Their only specific guidance for cover songs is in their Copyright FAQ, which says, “Recording a cover version of your favorite song does not necessarily give you the right to upload that recording without permission from the owner of the underlying music.”

But this answer isn’t fully accurate. YouTube’s negotiated blanket synchronization licenses for its users from thousands of publishers, most notably the settlement with the National Music Publishers Association last August. This agreement allowed publishers to opt-in to a program that let them take a cut from a $4 million advance pool and up to 50 percent of the advertising revenue from any cover song they own the rights to.

Frustratingly, we have no idea which publishers have signed on. The NMPA doesn’t publish the list, making it impossible to figure out whether your song is covered by the agreement or not. (I contacted the NMPA, but a spokesperson confirmed that information appeared to be unavailable, but was looking into it.)

Begging for Forgiveness

In reality, the only way to tell whether a song is legal is to risk breaking the law and losing your YouTube account — by uploading the video and waiting for copyright notices.

In the last few months, YouTube has quietly expanded Content ID beyond original recordings to detect cover versions and live performances using the underlying melodies. A YouTube representative confirmed with me, “Content ID’s technology allows us to identify works in an original sound recording, or in a cover version (by identifying the underlying melody of a song), using information provided to us by the publishers.”

YouTube hasn’t talked much about its melody matching technology, but it was in the news recently after a drunk Edmonton man belted “Bohemian Rhapsody” in the back of a police car. After the Content ID identified the song, EMI initially decided to take the video down, but soon changed its mind and authorized it with advertising.

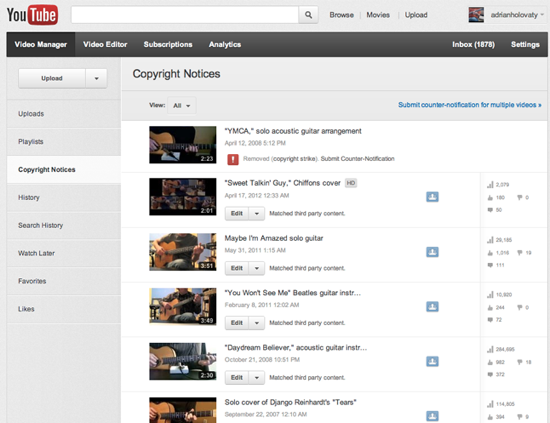

Adrian shared a screenshot of his copyright disputes page.

Everyblock founder Adrian Holovaty is well known on YouTube for his acoustic guitar covers, which have amassed millions of views. I asked him if Content ID identified the melodies in any of his videos. So far, seven of his videos were identified, with all but one rights holder choosing to leave the video online and collect the revenue. Only one video his cover of the Village People’s “YMCA,” was taken down by the songwriter, leaving Adrian with a “copyright strike” on his account. YouTube’s policy allows three strikes before the account is terminated and all videos removed.

The Flaws in the System

The system’s not perfect, though. Unscrupulous individuals are routinely using Content ID to claim content they don’t own to harvest ad dollars from unsuspecting users. For example, two of Adrian Holovaty’s disputed tracks are Django Reinhardt songs from the 1930s, claimed by an obscure company named “Social Media Holdings.”

Other copyright claims may be accidental, as material they don’t actually own finds its way into the Content ID database, like this poor guy who’s received eight consecutive claims from companies claiming to own George Romero’s public domain Night of the Living Dead.

And Content ID isn’t immune to false positives, like the bird calls misidentified as music. Worse, for all these case, disputed Content ID claims bypass the DMCA process for counter-claims entirely, as I wrote about in February.

How can a musician decide what’s legitimate or worth fighting?

Still, YouTube’s Content ID is pushing publishers and rights holders into the modern age. It’s an ingenious approach for an otherwise dysfunctional copyright system that’s too hard for amateurs to navigate, making money for everyone involved while still allowing free creative expression.

The Need for Change

But there’s something strange about this begging-for-forgiveness approach to copyright. It’s like driving without traffic signs, only finding out you broke the law when you’re pulled over.

The real question: Why is it illegal in the first place?

Cover songs on YouTube are, almost universally, non-commercial in nature. They’re created by fans, mostly amateur musicians, with no negative impact on the market value of the original work. (If anything, it increases demand by acting as a free promotional vehicle for the track.)

The best solution is the hardest one: To reform copyright law to legalize the distribution of free, non-commercial cover songs.

Copyright law was intended to foster creativity by making it safe for creators to exclusively capitalize on their work for a limited period of time. Cover songs on YouTube don’t threaten that ability, and may actually prevent new works by chilling talent that could go on to do great things.

As we’ve seen with countless breakout artists from YouTube, budding musicians have built their careers from cover songs that evolved into original material. Karmin, Pomplamoose, Julia Nunes, Greyson Chance…. Even Justin Bieber started with covers of Chris Brown and Nee-Yo before getting discovered.

Now, the next generation of budding pop stars are covering Justin Bieber, with about 216,000 of them so far. It’s all part of the virtuous cycle of culture: We take from it, build on it, and then give back in return. The law should help that along, not hinder it.

Update: I originally published this column over at Wired on May 2. The woman I spoke to at the NMPA confirmed the list of publishers appeared to be unavailable, but promised to look into it. I haven’t heard back, so I followed up again. I’ll update here if I hear anything.)

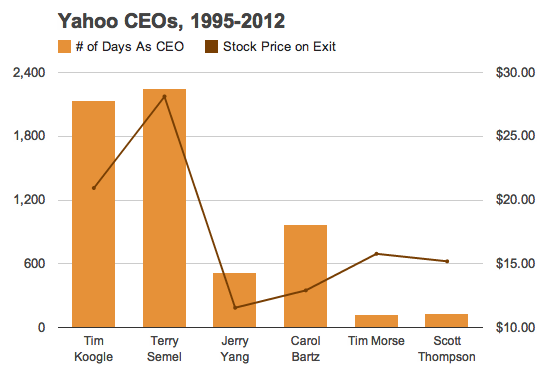

History of Yahoo CEOs: Tenure vs. Stock Price

Just for the hell of it, I charted the tenure for every one of Yahoo’s CEOs against the starting and ending stock price. Man, what a mess.

Just so nobody else ever has to do this, here’s the data, culled from Google News reports and YHOO stock quotes. Download as a CSV.