The First Round Capital Holiday Train Wreck

Your annual reminder of the hidden costs of taking venture capital is here — it’s the First Round Capital Holiday Video, a yearly cringe-fest of startups parodying the year’s biggest pop hits, with lyrics tweaked to reflect the worst of startup culture. (Full lyrics at the end of the post.)

I have a grim fascination with these videos and their ever-increasing production budgets. Every year, I watch them with my hands shielding my eyes, and collect them in a YouTube playlist. (For some reason, 2009’s video is only on Vimeo.)

Of course, if you ask First Round about it, and probably most of the founders in the video, they’ll say, it’s all in fun! We’re just blowing off some steam at the end of the year! I know one of the partners at First Round. I know some of the people at the startups in the videos. I don’t think their intentions are bad.

But once these startups have taken funding, do they really have a choice?

This year, Crunchbase says First Round invested in 57 startups, a median amount of $8.5M and an average of $18.5 million.

If someone gives you $8.5 million, sits on your board, and owns a significant part of your company, you’re going to dance if they say “dance.” You’re going to sing if they say “sing.”

And you’ll ask your entire team to do it too, and they’ll be captured on video, streamable on YouTube for years after they quit or were laid off.

In a situation like that, you can’t really say no. You just put on the costume, smile, and dance.

Continue reading “The First Round Capital Holiday Train Wreck”

If Drake Was Born A Piano

This morning, my friend Charles pointed me to a song on Tumblr that blew up, a remix of Mariah Carey’s “All I Want for Christmas Is You.”

The original poster deleted it, so I’m mirroring it here.

It’s a terrible and amazing thing to listen to — a conversion of the original MP3 to MIDI, and back again to MP3. The resulting version sounds like Mariah as a player piano — none of the original recording is preserved, only a series of hyperactive notes matching the frequencies of the original song.

Incredibly, you can still make out the lyrics and music, though likely only if you’re familiar with the original song.

It reminds me of this German project from 2009, in which Austrian composer Peter Ablinger used a computer-controlled piano to play a child’s voice.

So I had to try out a couple other songs to see how it sounds. I’m pretty happy with the results. Enjoy.

This scene always gets me. pic.twitter.com/u4WcbIZBTM

— Andy Baio (@waxpancake) December 16, 2015

And a bunch more on my Soundcloud playlist.

I used a web-based converter for the MP3 to MIDI conversion, and I used timidity and ffmpeg for the conversion back to MP3.

And, of course, just as I was finishing these videos, my friend Tim pointed out that Tim Troppoli tried this same technique earlier this year. And, go figure, he used Smash Mouth’s “All Star” too. It’s like the Lenna photo for audio.

More great examples in his video, including Piano Man and Stayin’ Alive. I’m not familiar with the Pokemon theme, and it was totally nonsensical to me. I can’t make out a single lyric, a great example of how your brain’s filling in the gaps.

Update: Here’s an example from 2009 of the same technique used on David Lee Roth’s isolated vocals from Van Halen’s Running with the Devil. And the vocals on this version of Oasis’ Wonderwall are particularly clear for me.

Lying With a Zero Axis

In June, data journalist David Yanofsky wrote a Quartz article about chart design, “It’s OK not to start your y-axis at zero.”

Last month, Vox followed with a more spirited defense of the practice, “Shut up about the y-axis. It shouldn’t always start at zero.”

Both publications noticed a common trend: any time they published a chart that truncated the y-axis, they’d get a bunch of angry emails and tweets claiming it’s deceptive. But Vox and Quartz are absolutely right — context matters, and often, starting a chart at a zero axis can mislead too.

Vox’s article led to some angry responses, like this one from writer Ramez Naam:

Seldom have I seen @voxdotcom get something so wrong. https://t.co/ErktflVKKH Truncating the Y-axis really is dishonest in most cases.

— Ramez Naam (@ramez) November 19, 2015

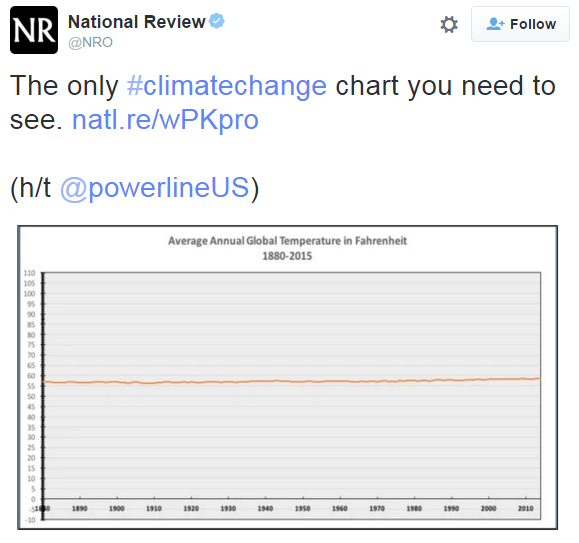

Today, the National Review tweeted this (now-deleted) incredibly misleading chart about climate change, inadvertently proving Quartz and Vox right.

Twitter had a field day with it.

it’s crazy how my height has barely changed at all my whole life pic.twitter.com/pqUyzr20NQ

— Seth D. Michaels (@sethdmichaels) December 14, 2015

@NRO @powerlineUS Why, I’ve barely changed! pic.twitter.com/lFsze2v8ES

— Jim Pettit (@jim_pettit) December 14, 2015

.@NRO @powerlineUS WOW!!!!! this chart shows gun violence isnt a issue either pic.twitter.com/TLGEjoHNmQ

— jomny sun (@jonnysun) December 14, 2015

The only #undocumentedimmigration chart you need to see. @NRO @powerlineUS #FunWithYAxes pic.twitter.com/3WJR4Ggd94

— Jeff Yang (@originalspin) December 14, 2015

Snark aside, here’s one way to make the chart meaningful again.

.@NRO @powerlineUS @bradplumer I’m sure someone else has fixed this for you, but here you go. Great idea, thx — pic.twitter.com/VxgcGalcSa

— City Atlas (@cityatlas) December 14, 2015

Tracking the "Trump Is A Comment Section Running for President" Joke

Donald Trump joined Twitter in March 2009, and announced his presidential campaign on June 16. Since then, if you’ve spent any time on Twitter, you’ve probably seen some variation of this joke:

Donald Trump is basically a YouTube comment section running for president

— Brian Gaar (@briangaar) December 7, 2015

This incarnation by Brian Gaar was posted last week, and got over 36,000 retweets.

But he’s hardly the first. Literally thousands of people have posted this sentiment, and I’ve personally seen several in my timeline with thousands of retweets.

Which got me thinking, who was the first and how did it evolve?

Let’s go back in reverse-chronological order, hitting some of the most popular versions.

On December 8, the day after Brian Gaar’s tweet last week, New York Magazine art critic Jerry Saltz got over 1,400 RTs with the same idea, this time adding an image.

Basically, Trump is what would happen if the comments section became human & ran for President. (h/t @Choire ) pic.twitter.com/LqJMhP1wdi

— Jerry Saltz (@jerrysaltz) December 8, 2015

Many people saw it from this tweet on November 22 by @mamasnark, which got over 10,200 retweets. (I see several people citing this tweet as the original when it reappears now.)

Basically, Trump is what would happen if the comments section became a human and ran for president.

— 8 nights of snark (@mamasnark) November 22, 2015

On November 10, Jon Stewart appeared at the Stand Up for Heroes benefit at Madison Square Garden and said, “It’s like an Internet comment troll ran for president.” This quote got extensive coverage from publications like the Hollywood Reporter, MSNBC, and Huffington Post.

Four days earlier, on November 6, Keith Olbermann appeared on Real Time with Bill Maher and said that Trump “sounds like an Internet comments section running for President.”

On August 7, Marc Andreesen tweeted it as an overheard comment, getting over 2,500 retweets.

OH: "Trump is like an Internet comments section decided to run for President."

— Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) August 8, 2015

On July 18, Barbara Haynes got over 13,000 RTs with this tweet that used the #DonaldTrump hashtag.

#DonaldTrump is like if a Comments Section ran for office.

— Barbara Haynes (@barbhaynes) July 18, 2015

On July 14, a Daily Kos blogger wrote, “Donald Trump is what would happen if a reddit comment thread ran for office.” This quote was picked up on Twitter.

On July 8, The Daily Beast’s Olivia Nuzzi got more than 2,700 retweets for her take on it.

Trump is like a YouTube comment thread that achieved sentience

— Olivia Nuzzi (@Olivianuzzi) July 9, 2015

Only a single day after Trump announced his presidency, on June 17, a Twitter user in Johannesburg drew a parallel to the News24 comments section and tweeted the idea — though as a reply and with no retweets, it was likely only seen by her 332 followers that also follow Trump.

@realDonaldTrump announcing his Presidential candidacy is like the News24 comments section running for President. Lord help us all.

— Posh Spice of Joburg (@MrsChida) June 17, 2015

But, of course, the idea that Trump is an Internet comments section goes back long before he announced his candidacy.

On April 28, this similar joke got 357 retweets.

Donald Trump is basically what would happen if every comments section on the internet merged, manifested into human form and put on a wig.

— Pat (╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻ (@PatsHoppedUp) April 28, 2015

On February 27, this minimalist take from @lafix for nearly 350 retweets.

Donald Trump is like if the comments section were a person.

— lafix (@lafix) February 27, 2015

How far back does this joke go? The earliest incarnation of the “Internet comment personified” idea on Twitter is this tweet by a guy named Mark on April 27, 2011.

Donald Trump is the living embodiment of an Internet message board troll.

— Mark (@PoorMeinNYC) April 27, 2011

So, did all these people rip off Mark?

No, of course not. I’ve written about the phenomenon of multiple discovery before, and nowhere is it more obvious and easily provable than in the comedy world, and especially easy to document on Twitter.

As Donald Trump came online, and as his prominence in the public eye grew, many more people started thinking about his behavior.

Of course, there are plagiarists in the world who brazenly copy jokes on Twitter, Instagram, and elsewhere, sometimes resulting in huge audiences.

But most people simply drew the connection between garbage Internet comment sections and the way Trump acts, and tweeted their epiphany.

So, settle in. It’s going to be a long year.

At this rate, 30% of all Twitter activity in 2016 will be "Donald Trump is a comments section running for President" jokes.

— Andy Baio (@waxpancake) December 14, 2015

Want many more examples? Oscar Bartos made @trump_comment, a bot dedicated to retweeting examples of this meme, and self-referential takes like this one.

Did I miss any major examples? Post a comment or tweet at me.

Psychonauts and Double Fine's Relentless Experimentation

Psychonauts is one of my favorite games of all time, the story of a psychic summer camp for kids, a government conspiracy, and love story rolled into one. The writing is funny and sweet, the characters and world wildly memorable, with some of the most inventive and innovative level design I’ve ever seen.

I first linked to the Psychonauts demo a week before its release in April 2005, and it still holds up incredibly well. If you’ve never played it, it’s deeply discounted on Steam in a $20 bundle with Broken Age, Grim Fandango Remastered, Brutal Legend, Costume Quest, and a bunch of other great Double Fine games for the ridiculous price for the next 16 hours. Or just pick it up for $10 normally.

It’s a miracle the game was ever released at all. As Double Fine’s first game, its development was notoriously fraught with major obstacles — a neverending crunch mode over 4.5 years of development, cancelled funding, and multiple near-death experiences. In the end, the game was released to critical acclaim and relatively weak sales, but built a deep and obsessive cult following over the last decade, eventually selling 1.7 million copies.

To commemorate the launch of their new campaign to fund its sequel, Double Fine and 2 Player Productions made a 50-minute short about the history of Psychonauts. It’s an incredible archive of Tim Schafer’s unseen video footage, design thinking, and interviews with the team talking about their experience making the game, good and bad.

Double Fine, more than any indie studio I know, is defined by its willingness to keep pushing itself to try new things. Some of these experiments work and some fall flat, with other indies able to watch and learn from the sidelines.

Their Kickstarter project for Broken Age paved the way for many other indie game developers and fans to use crowdfunding, and they documented it all in public with the Double Fine Adventure documentary, one of the best accounts of making anything ever, entirely free on YouTube. Their Amnesia Fortnight project, first internal and later public, encouraged experimentation within a team. Their Steam Early Access projects are perhaps the most controversial, with the cancellation of one game, though even that’s found a life of its own.

And, now, with the Psychonauts 2 campaign on Fig, they’re testing the waters for equity crowdfunding: the ability for members of the public to get a financial return on a crowdfunding project, rather than rewards alone.

(As a Kickstarter advisor and shareholder, I’m biased, but I have concerns about equity crowdfunding for indies. If you think backers feel entitled now, wait until they’re expecting a financial return.)

But I admire Double Fine for pushing everything forward, and I’m excited to see the results of their experiment. I supported the Double Fine Adventure, and of the 229 projects I’ve backed on Kickstarter, it’s still my personal favorite. I have my signed poster, backer shirt, and I played and loved Broken Age. But it was worth it for the documentary alone, seeing every exciting and painful moment of making the game with the people behind it.

So, of course, I backed the Psychonauts 2 project and I can’t wait to see what happens. If you want to come along for the ride, you can still back the project until January 12.

As a side note, I played a teeny, tiny role in this story.

Five years ago, when Kickstarter was only a year old and two years before Notch made headlines with a tweet, I read this Joystiq article by Justin McElroy, writing that Tim Schafer was open to making Psychonauts 2 if he could find a willing publisher.

I freaked out, asked my friend Brandon Boyer for an email intro, and sent this email to Tim Schafer on November 12, 2010.

Tim: Huge, huge fan of your work. I recently replayed Psychonauts, DOTT, and MI 1 and 2 with my six-year-old son. Just as good as I remembered.

Anyway, I showed the Joystiq article to the Kickstarter team and we’re all freaking out about the prospects of what Psychonauts 2 on Kickstarter might look like. Jamin from Kill Screen’s at the Kickstarter office right now and they’re all talking about it.

Going directly to fans to pre-sell the game before it exists sounds insane, but it’s very possible. It’s an incredible promotional tool, a great way to show there’s a market for the game to publishers, and doesn’t involve any kind of investment or preclude any kind of future publisher arrangements. And, of course, Kickstarter would promote the hell out of it to the community.

I’d love to introduce you to the team and answer any questions you might have, if you’d even *remotely* consider this.

I never heard back, but three years later, I invited Tim Schafer to speak at XOXO. There, for the first time, I heard the story of what happened after he received my email, the conversation that it kicked off internally at Double Fine with his business manager, and how it eventually led to the record-breaking Double Fine Adventure project. (The story starts at 17:30.)

Poker, Wikipedia, and the Singular They

Back in October, NPR’s Hidden Brain podcast covered the story of professional poker player Annie Duke, the only woman to compete in the World Series of Poker: Tournament of Champions in 2004.

It’s a fascinating story about her own impostor syndrome, feeling like she didn’t belong at that table, but also how she used gender stereotypes to work in her favor and eventually win the competition.

I love everything about this story. Once you’ve listened to it, I recommend watching the final moments of the game on YouTube.

For another perspective, Wil Wheaton pointed me to Annie Duke’s talk on The Moth, a gripping retelling in her own words of that tournament. It was the first time she’d ever played on television, and the first time anyone could see her hand.

While listening to the NPR story, I went looking for a refresher on the rules of Texas hold ’em, and ended up on this Wikipedia page for betting in Poker.

Immediately, I was struck by the language, which was dominated by male pronouns:

When it is a player’s turn to act, the first verbal declaration or action he takes binds him to his choice of action; this rule prevents a player from changing his action after seeing how other players react to his initial, verbal action.

If he declines to raise, he is said to “check his option.”

If a player borrows money to raise, he forfeits the right to go all-in later in that same hand — if he is re-raised, he ”must” borrow money to call, or fold.

And so on, for over 12,000 words. It felt like it was borrowed from another time, cribbed from a thrift shop poker book from the 1970s.

Because it was Wikipedia, I felt like I could do something about it. So I spent some time making the biggest edit I’ve ever made on Wikipedia: changing every male pronoun to gender-neutral language, sometimes rephrasing as “the player,” but often using the singular they. I tried to be careful about readability, making sure to only use it in cases where it couldn’t be confused with a plural group.

So “a player may fold by surrendering his cards” became “a player may fold by surrendering their cards.”

In the end, it took longer than I’d like to admit — over 160 changes in one big commit.

I saved it, tweeted about it, and promptly forgot about it.

While listening to @AnnieDuke on NPR yesterday, I looked up some poker rules on Wikipedia. All male pronouns. So… https://t.co/VifkHy4dPQ

— Andy Baio (@waxpancake) October 9, 2015

Yesterday, I remembered the change and popped over to Wikipedia to see if it survived.

Unsurprisingly, every change was reverted less than a week later. The user left a reason: “‘they’ is a plural term and inappropriate for an encyclopedia article.”

As it turns out, Wikipedia has its own guidelines about gender-neutral language. The Manual of Style recommends, “Use gender-neutral language where this can be done with clarity and precision. For example, avoid the generic he.”

A Wikipedia essay expands on the guideline, “There is no Wikipedia consensus either for or against the singular they… Although it is widely used in informal writing and speech, its acceptability in formal writing is disputed.”

Fortunately, that’s changing.

The singular “they” is one of the most hotly-debated subjects in exciting world of grammar. Last month, Dennis Baron declared it the “word of the year.”

Just last week, the Washington Post style manual became the latest to accept the pronoun. Bill Walsh, The Post’s copy editor, explains their decision:

There was one change, though, that I knew would cause controversy. For many years, I’ve been rooting for — but stopping short of employing — what is known as the singular they as the only sensible solution to English’s lack of a gender-neutral third-person singular personal pronoun. (Everyone has their own opinion about this.) He once filled that role, but a male default hasn’t been palatable for decades. Using she in a sort of linguistic affirmative action strikes me as patronizing. Alternating he and she is silly, as are he/she, (s)he and attempts at made-up pronouns. The only thing standing in the way of they has been the appearance of incorrectness — the lack of acceptance among educated readers.

What finally pushed me from acceptance to action on gender-neutral pronouns was the increasing visibility of gender-neutral people. The Post has run at least one profile of a person who identifies as neither male nor female and specifically requests they and the like instead of he or she. Trans and genderqueer awareness will raise difficult questions down the road, with some people requesting newly invented or even individually made-up pronouns. The New York Times, which unlike The Post routinely uses the honorifics Mr., Mrs., Miss and Ms., recently used the gender-neutral Mx. at one subject’s request. But simply allowing they for a gender-nonconforming person is a no-brainer. And once we’ve done that, why not allow it for the most awkward of those he or she situations that have troubled us for so many years?

Grammar manuals and copy editors may be slow to adapt to how the rest of the world uses language, but the increasing popularity of “they” reflects an increasingly gender-inclusive culture.

In the meantime, Wikipedia leaves the singular “they” in limbo, neither endorsed nor banned. Most of the arguments seem to boil down to some variation of “it looks ugly.”

But what’s uglier: a mismatch of number or a mismatch of gender? One is mildly irritating, maybe slightly confusing. The other is often insulting and alienating.

Language evolves, and there’s little prescriptivists can do to change it.

Eventually, they’ll have to suck it up, accept the cards on the table, and fold.

Though they’ll inevitably make a lot of noise in the process.