At the PAX East conference last year, a young man approached the microphone during the Q&A with Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins, creators of the popular Penny Arcade webcomic.

Instead of asking a question, he bellowed, “Welcome to ACTION CASTLE! You are in a small cottage. There is a fishing pole here. Exits are out.”

An awkward pause, followed by some giggling from the audience. “Is it our turn to say something?” said Mike.

“I don’t understand ‘is it our turn to say something,'” said the young man.

Instantly, Mike and Jerry understood, along with everyone in the audience born before 1978.

“Go out!” said Jerry.

“You go out. You’re on the garden path. There is a rosebush here. There is a cottage here. Exits are north, south, and in.”

The game was afoot.

They were playing Action Castle, the first of a series of live-action games based on classic text adventures from the late ’70s and early ’80s. Game designer Jared Sorensen calls the series Parsely, named after the text parsers that convert player input into something a computer can understand.

In Parsely games, the computer is replaced entirely by a human armed with a simple map and loose outline of the adventure. No hardware and no code; just people talking to people.

It’s a clever solution to complex problems that have plagued game designers for decades. How do we understand the player’s intent? Can we make AI characters act human, instead of like idiot robots? Is it possible to handle every edge case the player thinks of without working on this game for the next 10 years?

Making computers think and react like us is hard. So instead of making software more human, some game developers are trying to make humans more like software.

It’s a similar approach used by Amazon for Mechanical Turk — their motto is “artificial artificial intelligence.” By layering an API over an anonymous human workforce, developers can solve problems that are best tackled by humans, but without the messiness of actual human communication.

Projects like Soylent add another layer of abstraction, invisibly embedding Mechanical Turk in Microsoft Word to crowdsource tedious tasks like proofreading and summarizing paragraphs of text. The effect feels weirdly magical, like technology that beamed in from the future.

In the gaming world, this substitution usually feels less like magic and more like robotic performance art. These performers are software-inspired actors — people pretending they’re videogames.

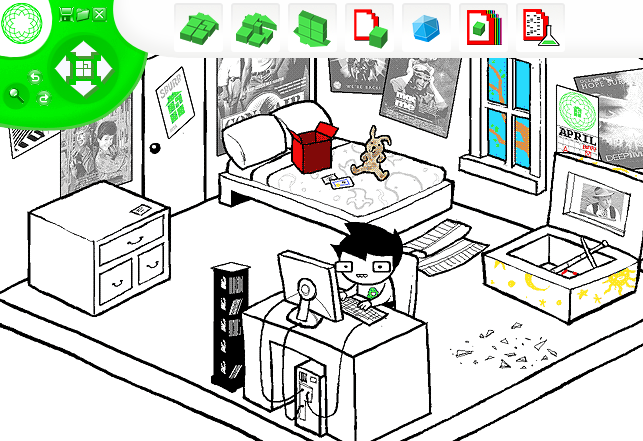

Nobody knows more about acting like a videogame than webcomic artist Andrew Hussie. Since 2006, he’s been running MS Paint Adventures, a series of increasingly insane reader-driven comics in the style of text-based graphical adventure games.

His first adventure, Jailbreak, started with a series of simple drawings posted on a discussion forum. With every new post, commenters would suggest new commands to further the gameplay, which he’d rapidly draw.

Hussie didn’t invent the genre — that honor likely goes to Ruby Quest and other denizens of 4chan’s gaming forums — but he certainly popularized it.

In the process, he became the world’s most prolific web cartoonist, sometimes updating up to 10 times a day.

To get a sense of the scale, Problem Sleuth, his second adventure, spanned over 1,600 pages in one year. Homestuck, his latest adventure, contains a staggering 4,100 pages so far, making it the longest webcomic of all time in a mere 2.5 years. And he still has a ways to go, with act five (out of seven) wrapping up just last week. (By comparison, the Guinness Book of World Records cites Mr. Boffo creator Joe Martin as the world’s most prolific cartoonist, with a mere 1,300 comics yearly.)

Over time, Hussie’s experimented with the amount of reader input. With Jailbreak, he drew the first command posted after every image, but as the adventures grew in popularity — it currently averages 600,000 unique visitors daily — this grew wildly impractical.

“When a story begins to get thousands of suggestions, paradoxically, it becomes much harder to call it truly ‘reader-driven,'” wrote Hussie on his website. “This is simply because there is so much available, the author can cherry-pick from what’s there to suit whatever he might have in mind, whether he’s deliberately planning ahead or not.”

With his newest adventure, Hussie leans on reader input less frequently and less directly, but involves the community in other ways. (For example, they just published their eighth soundtrack album of songs entirely created by fans. Don’t get me started on the cosplay.)

MS Paint Adventures goes where no videogame can possibly go, with insane storylines, shifting rules, and a ridiculous number of objects to interact with.

In any game, every object or action added to the game multiplies the number of possible interactions. Add a gun, and the programmer needs to deal with players shooting every single other object in the game. Add a lighter, and you’d better prepare for players burning everything in sight. Math geeks call this combinatorial explosion.

Homestuck’s bizarre alchemy system supports 280 trillion combinations. But Hussie doesn’t need to draw them all, only the ones readers actually try.

Reader-driven games give the illusion of limitless options, at the cost of scale. Even at 1,600 pages per year, player demand far outstrips the efforts of a single cartoonist.

Frustrated with emotional expression in computer games, game design veteran Chris Crawford set out to build Storytron, a storytelling engine intended to model the drama and emotional complexity with computer-generated actors. Eighteen years later, Crawford is still working on it and emotional AI seems just as far out of reach.

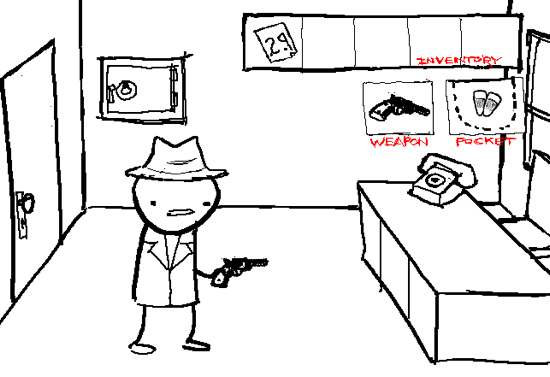

Jason Rohrer, creator of the critically acclaimed art-game Passage, tackled the problem of emotional depth in a different way — he replaced the computer AI with a human.

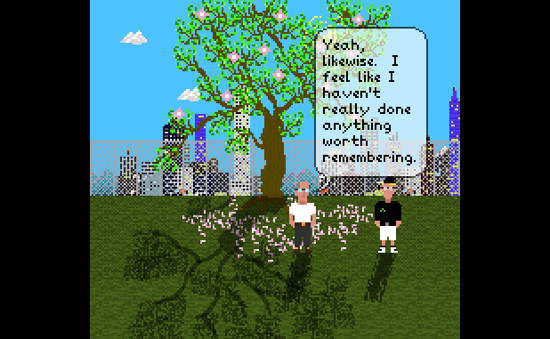

Last year, he released Sleep Is Death, a quirky storytelling environment that connects a single player to a single “controller” over the network. The player has 30 seconds to make any move they can think of, and the controller scrambles to manipulate the scene to respond using a set of drawing tools.

The world is completely open-ended. The only limitation is the imagination of the player and controller.

As you’d expect, the results vary wildly, often depending on the relationship between the participants, but it’s always surprising in a way that many traditional videogames aren’t. Try browsing through SIDTube, the community-contributed gallery of Sleep Is Death playthroughs, and you’ll find everything from a child’s eye view of Hiroshima to meditations on growing old with friends.

Every playthrough is completely unique, a singular experience improvised by two people. Is that a game or performance art?

Earlier this year, a German theater group named Machina eX began staging live performances based on “point-and-click” adventure games like Secret of Monkey Island and Machinarium.

On the surface, Machina eX resembles other immersive performances like Tamara or Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, with audience members following oblivious actors around elaborately-designed rooms.

In Machina eX’s performances, actors periodically get stuck in a loop, like a game paused. The audience must step in to solve the puzzle by manipulating objects in the room before the story can continue.

Each of these projects pull together elements of improvisational theater, performance art, and role-playing games.

But it’s the lens of videogames that separates them from Dungeons & Dragons, TheatreSports, and countless other collaborative games.

Each game borrows the conventions of a familiar game genre, preparing anyone who plays it with a set of expectations — the fundamental rules, terminology, constraints, and affordances are all well-known. Even better, storytellers can subvert any of those expectations at any time.

And unlike a game engine, human storytellers can go off-script. In the case of MS Paint Adventures, they can even switch game genres entirely, as Andrew Hussie’s done with Homestuck’s evolution from adventure game to Sims-style simulation to traditional RPG to whatever the hell this is.

Using live, real-time human ingenuity as the engine for videogames creates completely new, unexpected experiences unlike anything you can code.

In The Diamond Age, Neal Stephenson imagines a world where AI is extremely powerful, but still not convincing enough to convincingly simulate human behavior. Instead, AI characters are replaced by “ractors” — paid human actors who perform in virtual worlds for entertainment and education.

Even the all-powerful Wizard 0.2, the most powerful Turing machine in the land, is actually only used for data collection and processing — the real decisions are made by the man behind the curtain.

Chris Crawford and Peter Molyneux spent years trying to find Milo, but I think we’ll be waiting for a while yet.

In the meantime, I’m going to go pretend a game or two.

If you haven’t seen it, there was a good running sketch on a BBC Scotland show last year, depicting a fictional premium-rate phoneline where the host would guide their caller through a text adventure (possibly inspired by the FIST phonelines from the 80s):-

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qyYg_bfrlw

It reminds me of the Primer in Neal Stephenson’s “The Diamond Age (or A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer)”.

Since Ruby Quest has a reference to Problem Sleuth in it’s first chapter, I’m pretty sure that Problem Sleuth came before Ruby Quest… and Jailbreak came before Problem Sleuth, but they’re both by Andrew Hussie so Hussie should get the credit.

I actually take pleasure in individuals just like you! Be mindful! !