Tracking the U.S. Government’s Response to #Occupy on Twitter

It’s no exaggeration to say that Occupy Wall Street first started on Twitter. As the New York Times reported Monday, the #occupywallstreet hashtag was conceived in July, a full two months before the first tent was pitched at Zuccotti Park.

As it grew from a single camp into a movement, Twitter was essential for getting real-time updates out as events unfolded, for both supporters and local government.

Particularly in the last month, some city officials have used Twitter as a tool to keep people informed. Even as they were dismantling camps, the mayors of New York City and Portland, Oregon were posting real-time updates and responding to citizens directly.

While city officials have actively communicated their positions, the response from the federal government has been muted, at best. The Occupy movement’s concerns are much larger than city politics, with most proposed demands requiring cooperation from Washington.

So far, official statements are isolated and infrequent — an early endorsement from the president, a couple of statements from the White House press secretary, and a range of opinions from individual members of Congress.

But maybe the situation’s different online? Twitter is much more casual and conversational, and social media-savvy federal agencies often respond directly to queries and complaints from their followers. It’s possible that federal employees are addressing questions and concerns about Occupy on Twitter instead.

I decided to find out.

Data Wrangling

I originally gathered this data to build the Federal Social Media Index, a weekly report that compares federal agencies using Twitter, which I’m happy to release today as part of my work at Expert Labs.

Starting with an index of over 450 U.S. government departments and agencies, I asked the anonymous workforce at Amazon Mechanical Turk to find official Twitter accounts for each one.

Three workers researched each agency, and I approved the ones they agreed on and hand-checked the rest.

When I was done, I had a list of 126 official Twitter accounts representing a wide swath of U.S. government, from the Secret Service to the Postal Service. (Browse them all on the Federal Social Media Index or in the spreadsheet below.)

To collect all the tweets, I used ThinkUp, a free, open-source tool for archiving and analyzing social-media activity on Twitter, Facebook, and Google+ that I work on at Expert Labs.

With this dataset, I could easily tell which federal agency is the most popular (NASA), the most prolific (the NEA), and the most likely to reply to you personally (the US Census Bureau).

It also makes it very easy to see who’s talking about Occupy, and who isn’t.

Occupy Silence

Since the Occupy protests started in mid-September, nearly 15,000 messages were posted by the 126 federal Twitter accounts.

Of those accounts, only three have mentioned the Occupy protests in any way — Voice of America, the Smithsonian, and the White House.

For those unfamiliar with it, VOA is a radio and television news network broadcasting in 100 countries in 59 languages, but banned from airing in the United States because of propaganda laws. As part of their daily news coverage, they’ve tweeted about Occupy nine times since the protests began. (Here’s the most recent.)

Second, the Smithsonian responded to a tweet by Complex Magazine, refuting rumors of an OWS-themed museum exhibit.

The only other mention of the Occupy protests: one tweet from the White House nearly two months ago.

Opening Up

The obvious reason for the silence is that the federal government doesn’t yet have a position on Occupy. If they haven’t issued a formal statement, blog post, or press conference, then why Tweet?

For starters, it’s a humane and natural way to open a dialogue with a generally forgiving audience. Some of these agencies have tens or hundreds of thousands of people who care about what they have to say, or they wouldn’t be following them.

Proactively talking about potentially challenging issues like Occupy is an opportunity to bring some humanity to government, and maybe even help shape policy.

(Note: This was originally published in my column in WIRED.)

Viewing the UC Davis Pepper Spraying from Multiple Angles

I was stunned and appalled by the UC Davis Police spraying protestors, but struck by how many brave, curious people recorded the events. I took the four clearest videos and synchronized them. Citizen journalism FTW. Sources below.

Best viewed in HD fullscreen.

Top

briocloud, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K8Uj1cV97XQ

jamiehall1615, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wuWEx6Cfn-I

Bottom

OperationLeakS, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BjnR7xET7Uo

Google Analytics A Potential Threat to Anonymous Bloggers

Last month, an anonymous blogger popped up on WordPress and Twitter, aiming a giant flamethrower at Mac-friendly writers like John Gruber, Marco Arment and MG Siegler. As he unleashed wave after wave of spittle-flecked rage at “Apple puppets” and “Cupertino douchebags,” I was reminded again of John Gabriel’s theory about the effects of online anonymity.

Out of curiosity, I tried to see who the mystery blogger was.

He was using all the ordinary precautions for hiding his identity — hiding personal info in the domain record, using a different IP address from his other sites, and scrubbing any shared resources from his WordPress install.

Nonetheless, I found his other blog in under a minute — a thoughtful site about technology and local politics, detailing his full name, employer, photo, and family information. He worked for the local government, and if exposed, his anonymous blog could have cost him his job.

I didn’t identify him publicly, but let him quietly know that he wasn’t as anonymous as he thought he was. He stopped blogging that evening, and deleted the blog a week later.

So, how did I do it? The unlucky blogger slipped up and was ratted out by an unlikely source: Google Analytics.

Reverse Lookups

Typically, Google will only reveal a user’s identity with a federal court order, as they did with a Blogger user who harassed a Vogue model in 2009.

But anonymous bloggers are at serious risk of outing themselves, simply by sharing their Google’s Analytics ID across the sites they own.

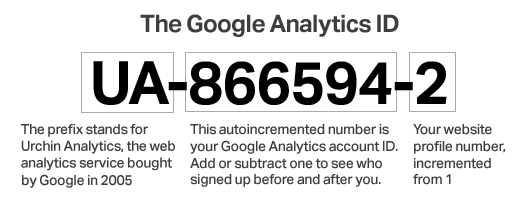

If you’re watching your pageviews, odds are you’re using Google to do it. Launched in 2005, Analytics is the most popular web statistics service online, in use by half of Alexa’s top million domains.

For the last few years, online SEO tools have published Analytics and AdSense IDs for the domains they crawl publicly, typically for competitive intelligence, such as ferreting out your competitor’s other websites.

But in the last year, several free services such as eWhois and Statsie have started offering reverse lookup of Analytics IDs. (Most also allow searching on the Google AdSense ID, though I wasn’t able to find an anonymous blogger sharing an AdSense ID across two sites.)

Finding anonymous bloggers from Analytics is less likely than other methods. It’s still more likely that someone would slip up and leave their personal info in their domain or share a server IP than to share a Google Analytics account. But it’s also more accurate. Hundreds or thousands of people can share an IP address on a single server and domain information can be faked, but a shared Google Analytics is solid evidence that both sites are run by the same person.

And unlike any other method, it can unmask people using hosted blogging services. Tumblr, Typepad and Blogger all have built-in support for Google Analytics, though reverse lookup services haven’t comprehensively indexed them. (Note that WordPress.com doesn’t support Analytics or custom Javascript, so their users aren’t affected.)

Just to be clear, this technique isn’t new. The first Google Analytics reverse lookup services started in 2009, so the technique’s been possible for at least two years. My concern is that it isn’t nearly well-known enough. It’s not mentioned in any guide to anonymous blogging I could find and several established bloggers, engineers, and entrepreneurs I spoke to were unaware of it.

Unmasking an anti-Mac blogger may not be life-changing, but if you’re an anonymous blogger writing about Chinese censorship or Mexican drug cartels, the consequences could be dire.

I decided to see how pervasive this problem is. Using a sample of 50 anonymous blogs pulled from discussion forums and Google news, only 14 were using Google Analytics, much less than the average. Half of those, about 15% of the total, were sharing an analytics ID with one or more other domains.

In about 30 minutes of searching, using only Google and eWhois, I was able to discover the identities of seven of the anonymous or pseudonymous bloggers, and in two cases, their employers. One blog about Anonymous’ hacking operations could easily be tracked to the founder’s consulting firm, while another tracking Mexican cartels was tied to a second domain with the name and address of a San Diego man.

I’ve contacted each to let them know their potential exposure.

Protecting Yourself

Some of the most important and vital voices online are anonymous, and it’s important to understand how you’re exposed. Forgetting any of these can lead to lawsuits, firings, or even death.

If you’re aware of the problem, it’s very easy to avoid getting discovered this way. Here are my recommendations for making sure you stay anonymous.

- Don’t use Google Analytics or any other third-party embed system. If you have to, create a new account with an anonymous email. At the very least, create a separate Analytics account to track the new domain. (From the “My Analytics Accounts” dropdown, select “Create New Account.”)

- Turn on domain privacy with your registrar. Better, use a hosted service to avoid domain payments entirely.

- If you’re hosting your own blog, don’t share IP addresses with any of your existing websites. Ideally, use a completely different host; it’s easy to discover sites on neighboring IPs.

- Watch your history. Sites like Whois Source track your history of domain and nameserver changes permanently, and Archive.org may archive old versions of your site. Being the first person to follow your anonymous Twitter account or promote the link could also be a giveaway.

- Is your anonymity a life-or-death situation? Be aware that any service you use, including your own ISP, could be forced to reveal your IP address and account details under a court order. Use shared computers and an anonymous proxy or Tor when blogging to mask your IP address. Here’s a good guide.

Stay safe.