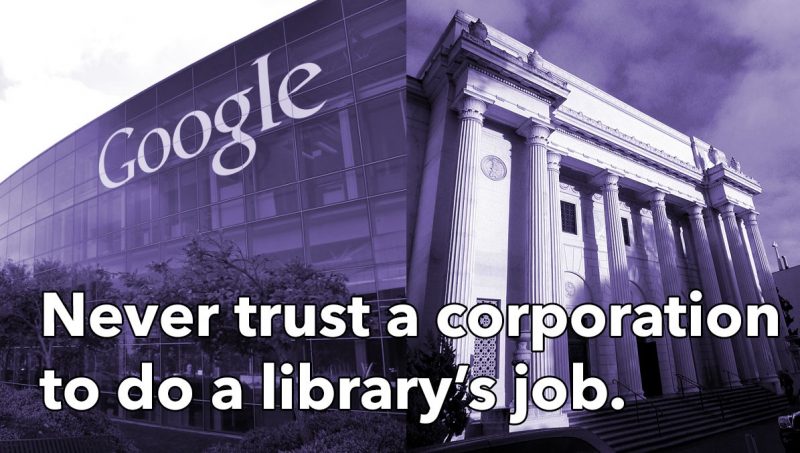

Never Trust A Corporation To Do A Library’s Job

As Google abandons its past, Internet archivists step in to save our collective memory

Google wrote its mission statement in 1999, a year after launch, setting the course for the company’s next decade:

“Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”

For years, Google’s mission included the preservation of the past.

In 2001, Google made their first acquisition, the Deja archives. The largest collection of Usenet archives, Google relaunched it as Google Groups, supplemented with archived messages going back to 1981.

In 2004, Google Books signaled the company’s intention to scan every known book, partnering with libraries and developing its own book scanner capable of digitizing 1,000 pages per hour.

In 2006, Google News Archive launched, with historical news articles dating back 200 years. In 2008, they expanded it to include their own digitization efforts, scanning newspapers that were never online.

In the last five years, starting around 2010, the shifting priorities of Google’s management left these archival projects in limbo, or abandoned entirely.

After a series of redesigns, Google Groups is effectively dead for research purposes. The archives, while still online, have no means of searching by date.

Google News Archives are dead, killed off in 2011, now directing searchers to just use Google.

Google Books is still online, but curtailed their scanning efforts in recent years, likely discouraged by a decade of legal wrangling still in appeal. The official blog stopped updating in 2012 and the Twitter account’s been dormant since February 2013.

Even Google Search, their flagship product, stopped focusing on the history of the web. In 2011, Google removed the Timeline view letting users filter search results by date, while a series of major changes to their search ranking algorithm increasingly favored freshness over older pages from established sources. (To the detriment of some.)

Two months ago, Larry Page said the company’s outgrown its 14-year-old mission statement. Its ambitions have grown, and its priorities have shifted.

Google in 2015 is focused on the present and future. Its social and mobile efforts, experiments with robotics and artificial intelligence, self-driving vehicles and fiberoptics.

As it turns out, organizing the world’s information isn’t always profitable. Projects that preserve the past for the public good aren’t really a big profit center. Old Google knew that, but didn’t seem to care.

The desire to preserve the past died along with 20% time, Google Labs, and the spirit of haphazard experimentation.

Google may have dropped the ball on the past, but fortunately, someone was there to pick it up.

The Internet Archive is mostly known for archiving the web, a task the San Francisco-based nonprofit has tirelessly done since 1996, two years before Google was founded.

The Wayback Machine now indexes over 435 billion webpages going back nearly 20 years, the largest archive of the web.

For most people, it ends there. But that’s barely scratching the surface.

Most don’t know that the Internet Archive also hosts:

- Books. One of the world’s largest open collections of digitized books, over 6 million public domain books, and an open library catalog.

- Videos. 1.9 million videos, including classic TV, 1,300 vintage home movies, and 4,000 public-domain feature films.

- The Prelinger Archives. Over 6,000 ephemeral films, including vintage advertising, educational and industrial footage.

- Audio. 2.3 million audio recordings, including over 74,000 radio broadcasts, 13,000 78rpm records, and 1.7 million Creative Commons-licensed audio recordings.

- Live music. Over 137,000 concert recordings, nearly 10,000 from the Grateful Dead alone.

- Audiobooks. Over 10,000 audiobooks from LibriVox and more.

- TV News. 668,000 news broadcasts with full-text search.

- Scanning services. Free and open access to scan complete print collections in 33 scanning centers, with 1,500 books scanned daily.

- Software. The largest collection of historical software in the world.

That last item, the software collection, may start to change public perception and awareness of the Internet Archive.

Spearheaded by archivist/filmmaker Jason Scott, the software preservation effort began on his own site in 2004 with a massive collection of shareware CD-ROMs from the BBS age.

After he joined the Internet Archive as an employee, he started shoveling all that vintage software onto their servers, along with software gathered from historic FTP sites, shareware websites, tape archives, and anything else he could find.

But actually using old software can be rough even for experienced geeks, often requiring a maze of outdated archival utilities, obscure file formats, and emulators to run.

In October 2011, Jason Scott wrote a call-to-arms aimed at making computer history accessible and ubiquitous — by porting classic systems to the browser.

“Without sounding too superlative, I think this will change computer history forever. The ability to bring software up and running into any browser window will enable instant, clear recall and reference of the computing experience to millions.”

The project started attempting a Javascript port of MESS, the incredible open-source project to emulate over 900 different computers, consoles, and hardware platforms, everything from the Atari 2600 and Commodore 64 to your old Speak & Spell and Texas Instruments graphic calculator.

Two years later, it was all real.

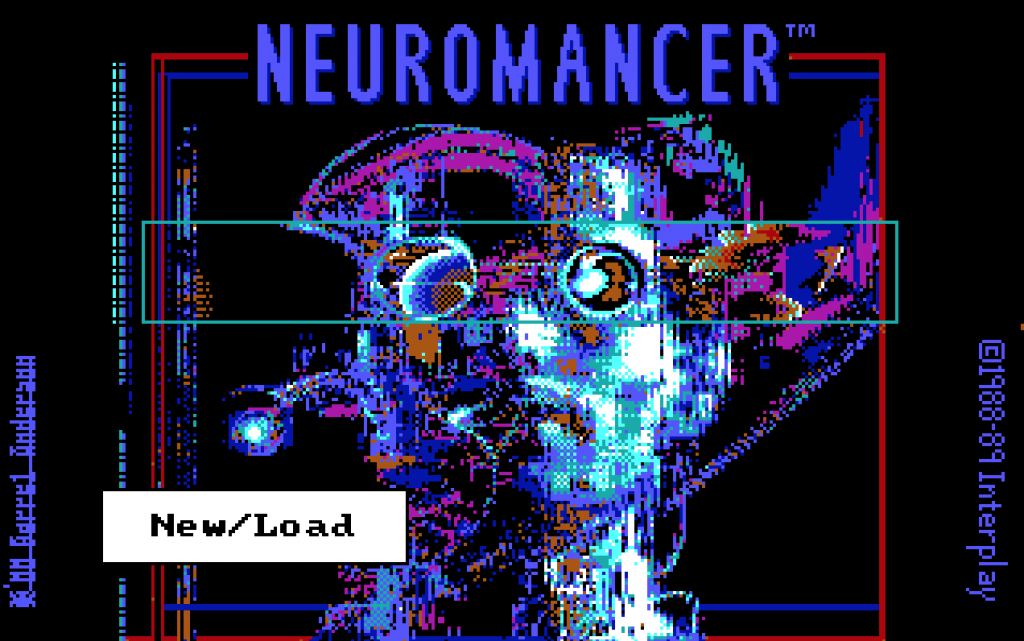

In October 2013, the Internet Archive tested the waters with the Historical Software Collection, 64 historic games and applications from computing history playable in the browser. No installation required — just one click, and you were trying out Spacewar! for the PDP-1, VisiCalc for the Apple II, or Pitfall for the Atari 2600.

By Christmas, they launched The Console Living Room, nearly 3,000 games from a dozen different consoles. Popular systems like the ColecoVision and Sega Genesis were represented, but also obscure and hard-to-find consoles like the Fairchild Channel F and Watara SuperVision.

A year later, they launched the Internet Arcade — hundreds of classic arcade games emulated with JSMAME, part of the JSMESS package.

Earlier this month, the Archive made headlines with the latest addition to its collection: nearly 2,300 vintage MS-DOS games, playable in the browser.

A technical breakthrough, the games are played on the popular DOSBox emulator, ported to Javascript by one brilliant, talented engineer.

The experience of clicking a link and playing a game you haven’t seen in 25 years is magical, and many other people felt the same way.

News of the MS-DOS Game Collection got widespread media coverage, including The Washington Post, The Verge, and The Guardian, with thousands of people hitting the site every minute.

Millions of people are discovering software they’ve never seen before, or revisiting games from their past. People are making Let’s Play videos of 30-year-old games, played in a Chrome tab.

When this launched, there were dozens of confused comments from people wondering what old videogames has to do with Internet history.

In my mind, this stems from mistaken perception issues of the Internet Archive as solely an institution saving webpages.

But their mission and motto is much broader:

Universal access to all knowledge.

The Internet Archive is not Google.

The Internet Archive is a chaotic, beautiful mess. It’s not well-organized, and its tools for browsing and searching the wealth of material on there are still rudimentary, but getting better.

But this software emulation project feels, to me, like the kind of thing Google would have tried in 2003. Big, bold, technically challenging, and for the greater good.

This effort is the perfect articulation of what makes the Internet Archive great — with repercussions for the future we won’t fully appreciate for years.

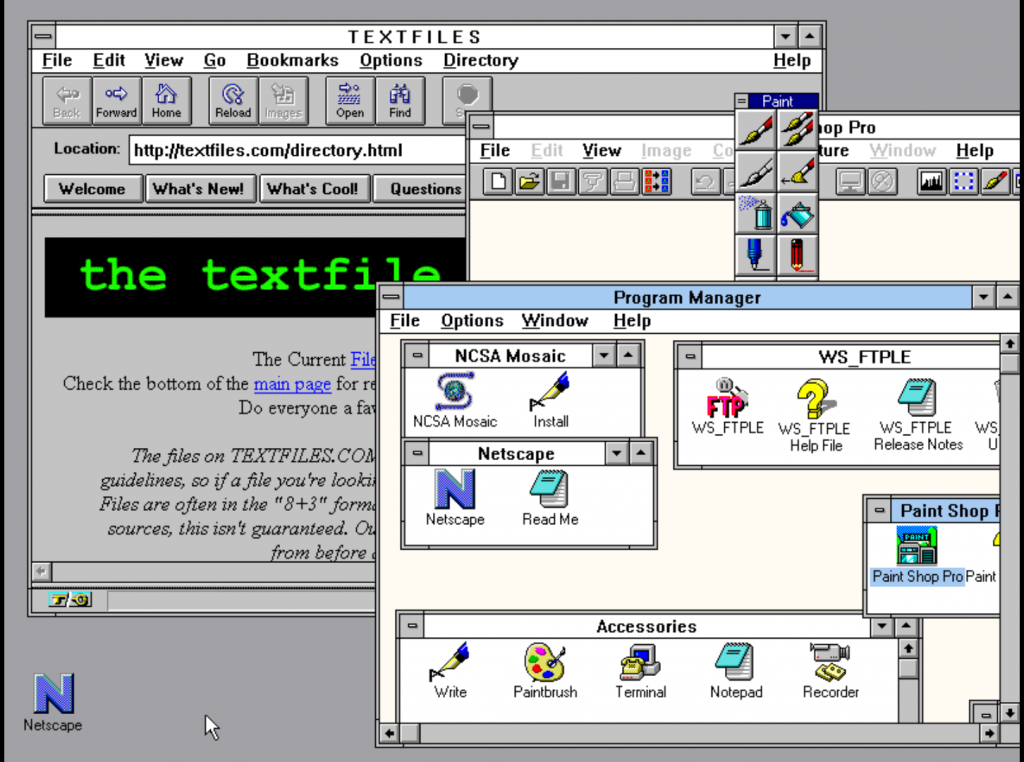

But here’s a glimpse: last week, one of the JSMESS developers managed to get Netscape running on Windows 3.1 with functional networking. All of computing history is within our grasp, accessible from a single click, and this is the first step.

It’s not just about games — that’s just the hook.

It’s about preserving our digital history, which as we know now, is as easy to delete as 15 years of GeoCities.

We can’t expect for-profit corporations to care about the past, but we can support the independent, nonprofit organizations that do.

This post was originally published in January 2015 on Medium as part of The Message.

Pirating the 2015 Oscars: HD Edition

In January 2004, the Los Angeles Times published an article headlined “Screener Ends Up on the Internet,” a story about the recent leak of the Something’s Gotta Give screener copy intended for Oscar voters.

This headline struck me as laughably clueless — like reading “Local Man Views Pornography On Internet” — but the MPAA statements inside were even more surreal, claiming it “marked the first time a so-called screener sent to an Oscar voter had been made available for illegal copying.”

Anyone who’d spent ten minutes on Usenet in the early 2000s knew this was nonsense. Oscar screeners leaked regularly and reliably, often with watermarks intact, typically around December and early January when they were mailed to Academy voters.

So I did a little digging and found that all but one of that year’s 22 nominated films were already online.

A decade later, it’s become an annual ritual for me.

On the morning the Oscar nominees are announced, I roll out of bed, load up some tabs, and start doing research into every nominated film.

The result is this Google Spreadsheet encompassing all 413 Oscar-nominated feature films for the last 13 years.

Along with the official U.S. and Oscar screener release dates, I include the leak dates for each major way that films typically find their way online:

- Cam. The old standby, a handheld camera in a theater. The worst quality, and increasingly uncommon.

- Telesync. Typically, a cam with better audio, often from headphone jacks in theater seats intended as hearing aids.

- Telecine, R5, PPV, Webrip, and HDRips. The terminology and sourcing’s changed through the years, but these are all high-quality rips with solid audio and video. (Generally speaking, Telecines were ripped from original prints distributed to theaters, R5 from “Region 5” DVDs sent to other regions to combat piracy, PPV from advanced pay-per-view sources, Webrip from early online releases like iTunes, and HDRip from a variety of sources, but typically from HDTV.)

- Screener. Great quality, usually intended for media or competition review, but can leak at any point in the distribution chain, often with watermarks intact. (As Ellen DeGeneres knows well.)

- Retail. A rip from the official retail release.

And then I use a little spreadsheet magic to calculate tables with a bunch of stats tracking how many films leaked online and how quickly.

Yes, this is my idea of a good time. I’m great at parties.

DVD In An HD World

In April 2004, the MPAA was already crowing about a decline in screener piracy, citing their watermarking technology and FBI assistance to increase accountability.

This was the start of a decade-long battle against screener piracy, but a funny thing happened in the last couple years:

Screeners weren’t declining then, but they’re declining now. But not because of increased accountability, watermarks, or new DRM technology.

Screeners aren’t leaking because they don’t matter anymore.

Think of it this way:

If you’re in a scene release group—one of the underground bands of misfits with names like SiMPLE, EVO, or TiTAN you see tagged in every torrent — you’re competing with dozens of others trying to release films online as quickly as possible, at the highest possible quality.

If you’re the first to release a highly-prized film in a high-quality release, you win bragging rights over every other group.

A release that’s lower quality than one already leaked by someone else? Completely worthless. A cam isn’t great, but a telesync is better. A telecine is marginally better than a telesync, but a watermarked screener? Much, much better.

But here’s the thing: screeners are stuck in the last decade. While we’re all streaming HD movies from iTunes or Netflix, the movie studios almost universally send screeners by mail on DVDs, which is forever stuck in low-resolution standard-definition quality. A small handful are sent in higher-definition Blu-ray.

This year, one Academy member received 68 screeners — 59 on DVD and only nine on Blu-ray. Only 13% of screeners were sent to voters in HD quality.

As a result, virtually any HD source is more prestigious than a DVD screener. And with the shift to online distribution, there’s an increasing supply of possible HD sources to draw from before screeners are ever sent to voters.

On December 27, Foxcatcher leaked online in HD quality by the release group EVO with hardcoded Arabic subtitles, a pretty strong indication it wasn’t sourced from a screener.

EVO released a new version without subtitles on January 6, captured from a 1080p source and released as a WEB-DL.

Even if someone did manage to get a copy of the Foxcatcher DVD screener right now, it’s unlikely it would ever be released. It’s garbage compared to either of these two releases — standard-definition and likely littered with watermarks or other dumb security precautions.

Now, in 2015, Oscar-nominated films leak online as quickly and consistently as ever.

Of this year’s 36 nominated films, 34 already leaked online in some form — everything except Song of the Sea and Glen Campbell: I’ll Be Me.

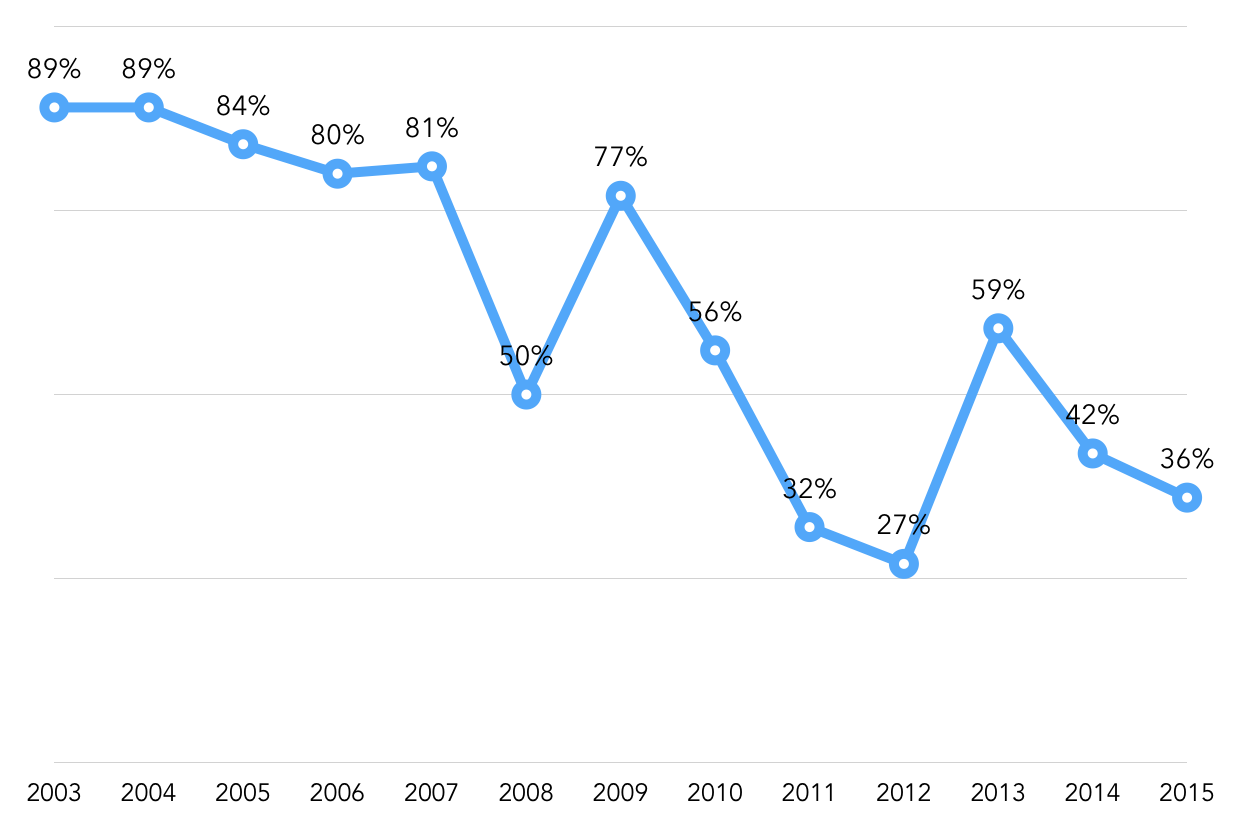

But only 36% of those were leaked from screeners, down from a high of 89% in 2003 and 2004.

With the caveat that there’s a month left before the Oscar ceremony, the chart below shows the percentage of screeners that have leaked online by Oscar night since 2003.

What the MPAA Thinks Is Leaking

Seems to be trending downward, right? The Academy must finally be winning the war against piracy! Huzzah!

Not so fast.

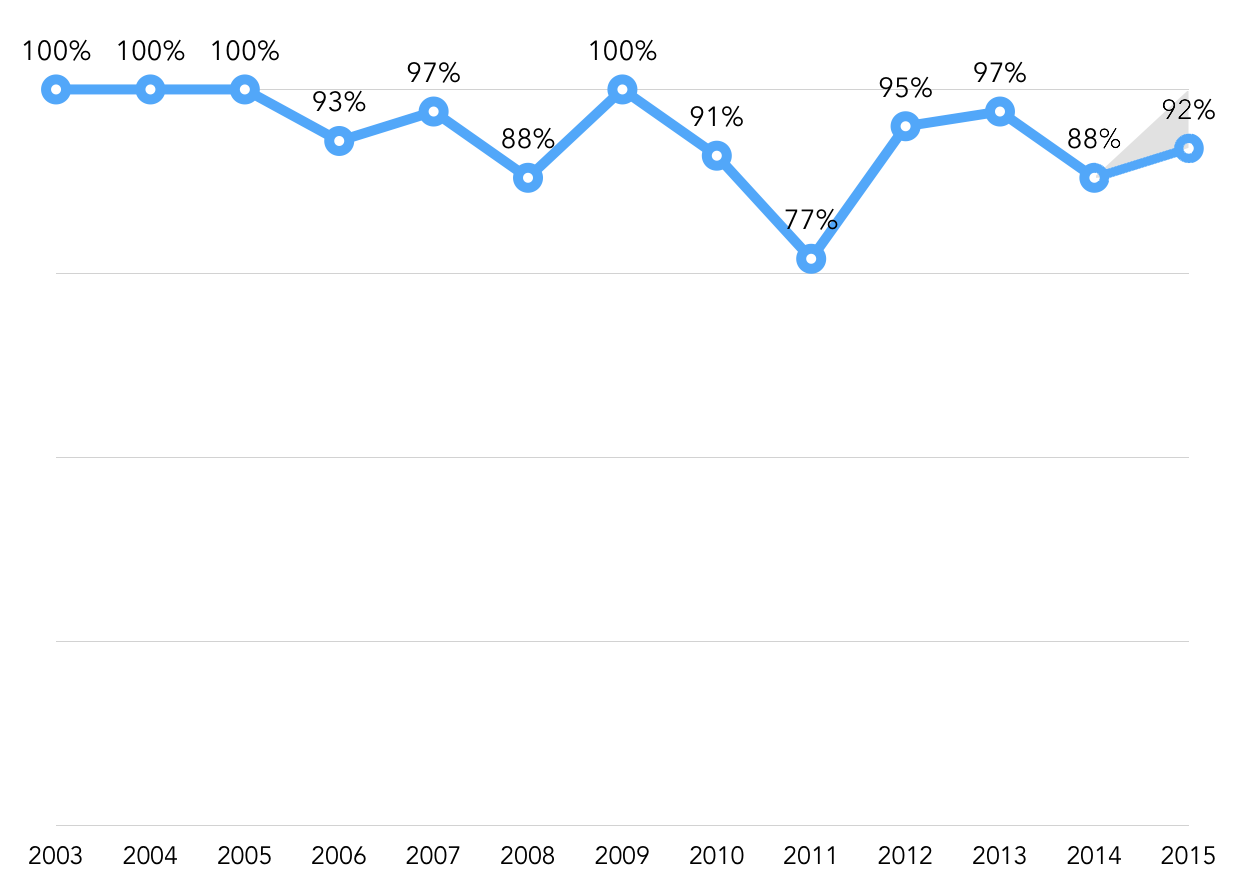

Here’s the percentage of films that have leaked in any high-quality format — whether ripped from the web, pay-per-view, retail or screeners — before Oscar night.

What’s Actually Leaking

Already, with a month to go before the ceremony, 92% of this year’s nominated films have already leaked in DVD or higher quality, more than last year. (Inevitably, this number will rise in the days leading up to the ceremony.)

The big change: A staggering 44% of this year’s crop of nominees leaked as a high-quality rip from some source outside of traditional screeners or retail releases — the highest percentage since I started tracking films in 2003.

The insatiable appetite for HD video led pirate groups to find new pipelines for sharing films before they even reach voters’ mailboxes, and in much better quality. These new sources for HD leaks, lurking anywhere from mastering studios to the mailroom, may be much harder for the MPAA to find than leaks from their own members.

Pirates are now watching films at higher quality than the industry insiders voting on them.

The industry’s reliance on DVDs for review copies, combined with their insistence on watermarks and other irritating security measures, made them undesirable in an HD world.

But the studios may not have a choice. Academy voters are an older crowd — the average age is 63 — who may not own Blu-ray players or be comfortable watching screeners online. If studios want their films viewed, they’re stuck stuffing DVDs in envelopes.

Eventually, the industry will need to adapt to digital distribution as DVDs die along with the oldest generation of voters.

Until then, Academy voters hoping to review HD films at home will have to do like the pirates do — grab some popcorn, turn down the lights, and fire up BitTorrent.

Notes on Methodology

For my spreadsheet, I include the full-length feature films in every Oscar category except documentary and foreign films — even music, makeup, and costume design.

I use IMDB for the release dates, always using the first available U.S. date, even if it was a limited release.

All the leak dates are taken from VCD Quality, supplemented by dates in ORLYDB. I always use the first leak date, excluding unviewable or incomplete nuked releases.

The official screener release dates are from Academy member Ken Rudolph, who kindly lists the dates he receives each screener on his personal homepage.

Questions, corrections, or additions? You can find me on Twitter.

(Note: I originally posted this article to The Message on Medium.)

Block With Abandon

Last week, my friend Jessamyn rounded up a list of Internet Resolutions from the writers of The Message, the blog/zine/thing I contribute to on Medium.

I don’t normally make New Year’s Resolutions, online or off, but I made an exception this year. Here’s mine:

“Block with abandon. I spent far too many emotional cycles last year on people arguing with me in bad faith, diving into arguments that could never be won. At some point, I stopped arguing and started blocking. I blocked hundreds of randos who insulted me or threatened people I admire— sea lions sauntering their way into my attention — and turned the Internet into something I could love again. Never. Again.”

As of today, I’ve blocked 603 accounts, the vast majority of those in the last three months.

Last month, I threw a Lazyweb request out into the ether:

I need a Chrome add-on to make Twitter blocking a one-click process. Something like this would be just great. pic.twitter.com/f1lQ1MJloR

— Andy Baio (@waxpancake) December 2, 2014

Within seconds, Phil Renaud replied:

@waxpancake on it

— Phil Renaud (@phil_renaud) December 2, 2014

A few days later, he delivered Twitter Quicker Blocker, a Chrome add-on that does one thing beautifully: it turns blocking into a one-click process from the Twitter website. (Two weeks later, Brian Henriquez made his own as a learning exercise.)

Here’s what that looks like:

For me, this was enough to make Twitter usable again. For those facing heavier abuse and harassment, tools like Block Together, GG Auto Blocker, and The Block Bot are out there.

Ideally, Twitter would provide better tools for managing your experience and coping with Internet assholes, but until then, I’m grateful to all the devs trying to make things better.