Arcade Improv: Humans Pretending to Be Videogames

At the PAX East conference last year, a young man approached the microphone during the Q&A with Mike Krahulik and Jerry Holkins, creators of the popular Penny Arcade webcomic.

Instead of asking a question, he bellowed, “Welcome to ACTION CASTLE! You are in a small cottage. There is a fishing pole here. Exits are out.”

An awkward pause, followed by some giggling from the audience. “Is it our turn to say something?” said Mike.

“I don’t understand ‘is it our turn to say something,'” said the young man.

Instantly, Mike and Jerry understood, along with everyone in the audience born before 1978.

“Go out!” said Jerry.

“You go out. You’re on the garden path. There is a rosebush here. There is a cottage here. Exits are north, south, and in.”

The game was afoot.

They were playing Action Castle, the first of a series of live-action games based on classic text adventures from the late ’70s and early ’80s. Game designer Jared Sorensen calls the series Parsely, named after the text parsers that convert player input into something a computer can understand.

In Parsely games, the computer is replaced entirely by a human armed with a simple map and loose outline of the adventure. No hardware and no code; just people talking to people.

It’s a clever solution to complex problems that have plagued game designers for decades. How do we understand the player’s intent? Can we make AI characters act human, instead of like idiot robots? Is it possible to handle every edge case the player thinks of without working on this game for the next 10 years?

Making computers think and react like us is hard. So instead of making software more human, some game developers are trying to make humans more like software.

It’s a similar approach used by Amazon for Mechanical Turk — their motto is “artificial artificial intelligence.” By layering an API over an anonymous human workforce, developers can solve problems that are best tackled by humans, but without the messiness of actual human communication.

Projects like Soylent add another layer of abstraction, invisibly embedding Mechanical Turk in Microsoft Word to crowdsource tedious tasks like proofreading and summarizing paragraphs of text. The effect feels weirdly magical, like technology that beamed in from the future.

In the gaming world, this substitution usually feels less like magic and more like robotic performance art. These performers are software-inspired actors — people pretending they’re videogames.

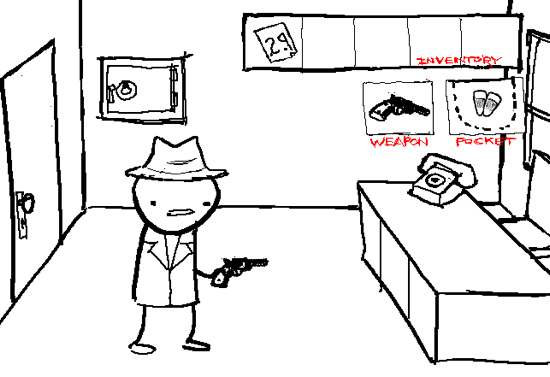

Nobody knows more about acting like a videogame than webcomic artist Andrew Hussie. Since 2006, he’s been running MS Paint Adventures, a series of increasingly insane reader-driven comics in the style of text-based graphical adventure games.

His first adventure, Jailbreak, started with a series of simple drawings posted on a discussion forum. With every new post, commenters would suggest new commands to further the gameplay, which he’d rapidly draw.

Hussie didn’t invent the genre — that honor likely goes to Ruby Quest and other denizens of 4chan’s gaming forums — but he certainly popularized it.

In the process, he became the world’s most prolific web cartoonist, sometimes updating up to 10 times a day.

To get a sense of the scale, Problem Sleuth, his second adventure, spanned over 1,600 pages in one year. Homestuck, his latest adventure, contains a staggering 4,100 pages so far, making it the longest webcomic of all time in a mere 2.5 years. And he still has a ways to go, with act five (out of seven) wrapping up just last week. (By comparison, the Guinness Book of World Records cites Mr. Boffo creator Joe Martin as the world’s most prolific cartoonist, with a mere 1,300 comics yearly.)

Over time, Hussie’s experimented with the amount of reader input. With Jailbreak, he drew the first command posted after every image, but as the adventures grew in popularity — it currently averages 600,000 unique visitors daily — this grew wildly impractical.

“When a story begins to get thousands of suggestions, paradoxically, it becomes much harder to call it truly ‘reader-driven,'” wrote Hussie on his website. “This is simply because there is so much available, the author can cherry-pick from what’s there to suit whatever he might have in mind, whether he’s deliberately planning ahead or not.”

With his newest adventure, Hussie leans on reader input less frequently and less directly, but involves the community in other ways. (For example, they just published their eighth soundtrack album of songs entirely created by fans. Don’t get me started on the cosplay.)

MS Paint Adventures goes where no videogame can possibly go, with insane storylines, shifting rules, and a ridiculous number of objects to interact with.

In any game, every object or action added to the game multiplies the number of possible interactions. Add a gun, and the programmer needs to deal with players shooting every single other object in the game. Add a lighter, and you’d better prepare for players burning everything in sight. Math geeks call this combinatorial explosion.

Homestuck’s bizarre alchemy system supports 280 trillion combinations. But Hussie doesn’t need to draw them all, only the ones readers actually try.

Reader-driven games give the illusion of limitless options, at the cost of scale. Even at 1,600 pages per year, player demand far outstrips the efforts of a single cartoonist.

Frustrated with emotional expression in computer games, game design veteran Chris Crawford set out to build Storytron, a storytelling engine intended to model the drama and emotional complexity with computer-generated actors. Eighteen years later, Crawford is still working on it and emotional AI seems just as far out of reach.

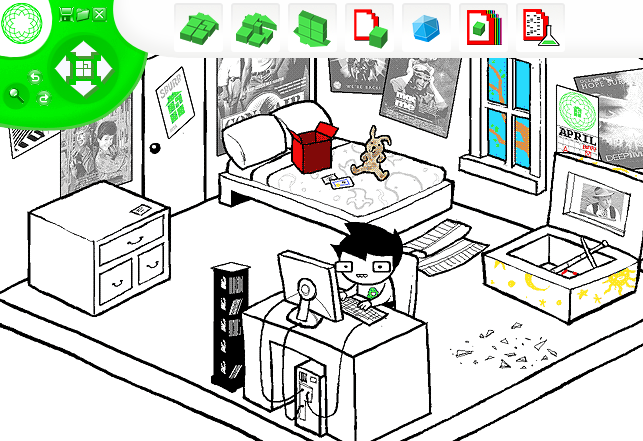

Jason Rohrer, creator of the critically acclaimed art-game Passage, tackled the problem of emotional depth in a different way — he replaced the computer AI with a human.

Last year, he released Sleep Is Death, a quirky storytelling environment that connects a single player to a single “controller” over the network. The player has 30 seconds to make any move they can think of, and the controller scrambles to manipulate the scene to respond using a set of drawing tools.

The world is completely open-ended. The only limitation is the imagination of the player and controller.

As you’d expect, the results vary wildly, often depending on the relationship between the participants, but it’s always surprising in a way that many traditional videogames aren’t. Try browsing through SIDTube, the community-contributed gallery of Sleep Is Death playthroughs, and you’ll find everything from a child’s eye view of Hiroshima to meditations on growing old with friends.

Every playthrough is completely unique, a singular experience improvised by two people. Is that a game or performance art?

Earlier this year, a German theater group named Machina eX began staging live performances based on “point-and-click” adventure games like Secret of Monkey Island and Machinarium.

On the surface, Machina eX resembles other immersive performances like Tamara or Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More, with audience members following oblivious actors around elaborately-designed rooms.

In Machina eX’s performances, actors periodically get stuck in a loop, like a game paused. The audience must step in to solve the puzzle by manipulating objects in the room before the story can continue.

Each of these projects pull together elements of improvisational theater, performance art, and role-playing games.

But it’s the lens of videogames that separates them from Dungeons & Dragons, TheatreSports, and countless other collaborative games.

Each game borrows the conventions of a familiar game genre, preparing anyone who plays it with a set of expectations — the fundamental rules, terminology, constraints, and affordances are all well-known. Even better, storytellers can subvert any of those expectations at any time.

And unlike a game engine, human storytellers can go off-script. In the case of MS Paint Adventures, they can even switch game genres entirely, as Andrew Hussie’s done with Homestuck’s evolution from adventure game to Sims-style simulation to traditional RPG to whatever the hell this is.

Using live, real-time human ingenuity as the engine for videogames creates completely new, unexpected experiences unlike anything you can code.

In The Diamond Age, Neal Stephenson imagines a world where AI is extremely powerful, but still not convincing enough to convincingly simulate human behavior. Instead, AI characters are replaced by “ractors” — paid human actors who perform in virtual worlds for entertainment and education.

Even the all-powerful Wizard 0.2, the most powerful Turing machine in the land, is actually only used for data collection and processing — the real decisions are made by the man behind the curtain.

Chris Crawford and Peter Molyneux spent years trying to find Milo, but I think we’ll be waiting for a while yet.

In the meantime, I’m going to go pretend a game or two.

Supercut: Anatomy of a Meme

I spent last weekend revisiting the “supercut” meme, with a talk at WFMU’s Radiovision conference in New York and my new Wired column, which you can read below.

To cap it off, I spent a night revamping Supercut.org into a comprehensive, browsable database of supercut videos, with the help of Twitter’s Bootstrap CSS toolkit.

I’m very happy with how the site came out, so let me know if you have any suggestions and please submit any videos I missed. I also just added RSS and you can now follow @supercutorg for updates. Thanks!

For the last few years, I’ve tracked a particular flavor of remix culture that I called “supercuts” — fast-paced video montages that assemble dozens or hundreds of short clips on a common theme.

Many supercuts isolate a word or phrase from a film or TV series — think every “dude” in The Big Lebowski or every profanity from The Sopranos — while others point out tired cliches, like those ridiculous zoom-and-enhance scenes from crime shows.

Since 2008, I’ve added every supercut I could find to a sprawling blog post. With nearly 150 of these videos, and more being added weekly, it’s turned from a blog post into a minor obsession.

Earlier this year, I collaborated with NYC-based artist Michael Bell-Smith on Supercut.org, a 24-hour hack to make a supercut composed entirely out of other supercuts, along with a randomized supercut browser.

Today, I’m happy to announce that I’ve relaunched the site to let you browse the entire collection in different ways, subscribe to updates, or submit your own to the growing list. I’m also releasing the entire dataset publicly, which you can download at the end of this post.

To understand the rise of this new genre, let’s take a look back at how it began and how it’s evolved in the last three years.

The Proto-Cuts

While the web popularized the genre, the art world was experimenting with similar film cut-ups for years before YouTube was a gleam in Chad & Steve’s eyes.

Brooklyn-based critic Tom McCormack wrote the definitive history of the supercut, tracing its origins back to found-footage cinema, like Bruce Conner’s A MOVIE from 1958.

But it wasn’t until the 1990s that clear descendants of the genre emerged. Matthias Müller’s Home Stories (1990) reused scenes from 1950s- and 1960s-era Hollywood melodramas, filmed directly from the TV set, to show actresses in near-identical states of distress.

Christian Marclay’s Telephones (1995) showed famous actors answering ringing telephones in a string of surreal, disjointed conversations throughout Hollywood history. Edited together, the cadence and rhythm of nonstop clips feels very reminiscent of modern supercuts.

Apple tried to license Marclay’s film for the launch of the iPhone in 2007, but he refused. Instead, they made their own, borrowing the idea wholesale. (Marclay decided not to sue.)

As far as I can tell, the earliest supercut native to the web was Chuck Jones’ Buffies from 2002, which isolated every mention of “Buffy” from the first season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

While there were rare exceptions, supercuts really didn’t start proliferating online until around 2006. Why then? The likely cause: YouTube.

Before YouTube, it was incredibly difficult to both find and share video. After YouTube’s launch in 2005, searching through big chunks of film and TV’s recorded history became simple. Perhaps more importantly, sharing the video with others didn’t require server space, a huge amount of bandwidth, and a deep knowledge of video codecs. It just worked.

The result was that clips were easy to find and even easier to distribute. Combined with the rise of BitTorrent and the availability of affordable, easy-to-use video editing software like iMovie, it was the perfect environment for video remixing. The only missing ingredient is the time and passion to make it happen.

Supercut as Criticism

When I first started tracking the trend in 2008, almost every example was created by a superfan. Creating videos with hundreds of edits takes a staggering amount of time, and the only people willing to do it were those who were in love with the source material.

In the last three years, the form seems to have evolved from fan culture to criticism.

Rich Juzwiak may have started the trend by calling out reality TV contestants for their overused “I’m not here to make friends” trope. That directly led to supercuts criticizing lazy screenwriting, from “We’ve got company” to “It’s gonna blow!”

But recently, it’s being used for more serious criticism: calling out politicians and the news media. The Daily Show pioneered the reuse of archival news footage and quick edits to point out the absurdity of the news media and political figures, but online video remixers are taking it much further.

Video remixing group Wreck & Salvage took Sarah Palin’s speech about the Arizona shootings and removed everything but the sound of her breathing. The result, Sarah’s Breath, was a creepy example of supercut as political speech.

In March, artist Diran Lyons released one of the most epic supercuts ever — chronicling every time President Obama says “spending” in the complete video archive posted to the White House website. The result is six minutes long with over 600 edits.

The results are effective. Just as it was used to point out film cliches, a supercut sends a message about a public figure’s speech in a very short period of time. For that reason, I wouldn’t be surprised to see supercuts make their way into 2012 campaign ads.

Breaking It Down

I wanted to learn more about the structure of these videos, so I enlisted the help of the anonymous workforce at Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to analyze the videos for me.

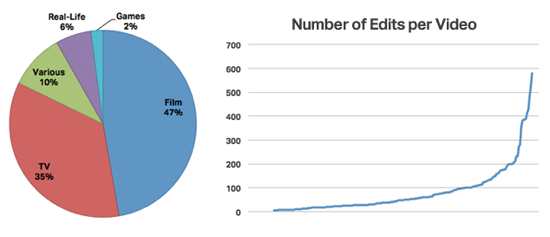

Using the database of 146 videos, I asked them to count the number of clips in each video, along with some qualitative questions about their contents. Their results were interesting.

When looking at the source of the videos, nearly half come from film with a little over one-third sourced from TV shows. The rest are a mix of real-life events, videogames, or a combination of multiple types, as you can see below.

According to the turker estimates, the average supercut is composed of about 82 cuts, with more than 100 clips in about 25% of the videos. Some supercuts, about 5%, contain over 300 edits!

I asked the turkers whether each supercut was comprehensive, collecting every possible example, or if they were just a representative sample. For example, collecting every one of Kramer’s entrances from Seinfeld vs. a selection of explosions from action films. The results were split, with about 60% comprehensive. This could be attributed to film cliche supercuts, which don’t attempt to be thorough.

Finally, I was wondering whether each video’s creator was a fan or critic of the source material. The workers surveyed said that most supercuts were created by fans, about 73% of the time. This style of video remixing may be useful for criticism, but for now, it seems to mostly be a labor of love.

The Data Dump

Want to do your own analysis, or do some video remixing of your own?

You can view the full supercut database below or on Google Docs, or download the data as a comma-separated text file or Excel spreadsheet.

And, of course, let me know if you find any that I missed!