Ten years ago, I started this site with three simple rules: no journaling, no tired memes, and be original. 18 months later, I added a little linkblog.

In those ten years, I’ve posted 415 entries, including this one, and over 13,000 links.

The decision to start writing here regularly changed my entire life. It’s given me exposure, a place to share my projects and crazy experimentation with technology. It’s created new opportunities for me, directly or indirectly responsible for every major project I’ve gotten involved in. It’s a place to play and experiment with ideas, some of which led to big breakthroughs and passions. And it connected me to people who cared about the things I did, many of whom became lifelong friends.

Personal homepages and weblogs have long since faded from the popular trends. They’re no longer hip and nobody’s launching the hot new startup to reinvent them or make them better.

Most of the interest in writing online’s shifted to microblogging, but not everything belongs in 140 characters and it’s all so impermanent. Twitter’s great, but it’s not a replacement for a permanent home that belongs to you.

And since there are fewer and fewer individuals doing long-form writing these days, relative to the growing potential audience, it’s getting easier to get attention than ever if you actually have something original to say.

Carving out a space for yourself online, somewhere where you can express yourself and share your work, is still one of the best possible investments you can make with your time. It’s why, after ten years, my first response to anyone just getting started online is to start, and maintain, a blog.

And now, just for the hell of it, some of my favorite posts from the last ten years. 🙂

2002

Tracking the All Your Base Meme with Usenet. The first chart appears only two weeks in, setting a precedent for the next ten years.

Dar Kabatoff’s In Town. My first deep-dive into Internet kookiness, an amazing example of Usenet lunacy that eventually led to my first stalker. To this day, people still link to this on various forums that Kabatoff appears in.

Spamming Weblog Comments. Where I casually predicted the rise of blog spam and Bayesian filters designed to stop it.

Steve Martin Fans. Another exploration into a sad, weird corner of the Internet, a prolific stalker turned suicidal in a Steve Martin fan forum.

October 2002 Dictionary Domains. I used to periodically run a script, check for the available of dictionary word .com, .org and .net domains, and post the results. Note the last one in the list, which I later snatched up for myself.

2003

Eldred, Shared Culture Loses. My first mashup landed me in the New York Times and Boston Globe, my first real press coverage ever. Soon after, a Disney exec bought a print of the comic from me, with the sale facilitated by Larry Lessig himself!

NYT and Lost Friends. Two weeks later, I was in the NYT again for my Lost Friends page. This was very new to me.

Google Buys Blogger. I was sitting front and center at the Blogosphere panel in Los Angeles when Ev announced Google bought Blogger, and was one of the first to report the news.

Bias Affects Story Updates on Political Weblogs. My first controversial tech exposé, manually analyzing sites to understand linking behavior. Most of these sites found my article from their referers, leading to some very upset bloggers. People don’t like to be accused of bias.

Typo Popularity Tracking with Google. I feel like I started to hit a stride with posts like these, doing some simple analysis to find entertaining results.

Star Wars Kid. The post that launched a meme, melting my server and the servers of most of my friends. I later tracked him down, interviewing him with Jish’s help and doing a fundraiser to buy him a newly-introduced iPod. Later, I reported on the lawsuits. Years later, I wrote a final summary of the whole thing, along with the logs for that period.

Santa Monica Farmer’s Market Tragedy. My personal reporting from a freak car accident that killed nine people outside my office led to coverage in the BBC. Horrifying.

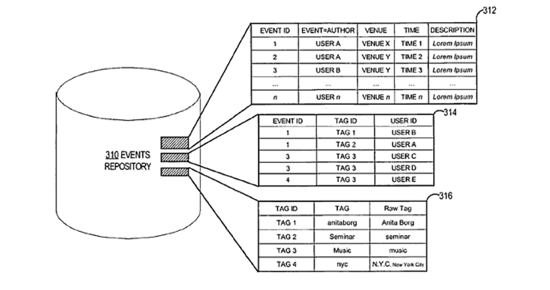

Upcoming.org Launch! The side project that changed my life.

2004

Researching the 2004 Oscar Screeners. Inspired by a delusional film industry, I sat down and tried to figure out exactly how often Oscar screeners leak online. Eight years later, I’m still doing it every year.

Waxy v2.0. Announcing our pregnancy and, a few months later, the birth of our son.

Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album. I was the first person to put the Grey Album on the web, leading to the first takedown request from EMI, which spawned the Grey Tuesday protests.

InfocomBot for AOL Instant Messenger. One of my favorite hacks ever, it let you play classic and modern text adventures over AIM.

Nanniebots: Hoax, Fraud, or Delusion? I helped Ben Goldacre and Cameron Marlow debunk a ridiculous hoax, someone who claimed he developed chatbots to lure pedophiles in chatrooms.

Waxy’s Bandwidth Blowout #1: Heat Vision and Jack. In the years before YouTube, serving video was a massive pain in the ass. If you were lucky enough to have a dedicated server, excess bandwidth was a handy commodity. I always loved hosting commercially-unavailable materials.

Amazon Knee-Jerk Contrarian Game. This post, tracking horrible Amazon reviews of critically-loved media, still makes me laugh.

Kleptones, “Night at the Hip-Hopera”. Still my favorite mashup album ever, I originally hosted a copy and crowdsourced the sample list for the Kleptones. It netted me my second cease-and-desist, this time from Disney/Hollywood Records.

Afro-Ninja Found! I managed to track down the identity of a stuntman having a very bad day.

Amateur Tsunami Video Footage. Another pre-YouTube phenomenon, the demand for this tragic disaster footage was so high, it melted my server and even took down Archive.org for a time. The videos I uploaded to Archive.org dominated their most downloaded lists for years.

2005

Boing Boing Statistics. I built a simple visualization tool for Boing Boing’s five-year archive, following my own Waxy.org Stats and Metafilter growth charts.

WordPress Website’s Search Engine Spam. The biggest story I’d ever broken, at that point, covering search engine spam hidden on WordPress.com. For me, this was a switch from casual blogging to serious journalism, including quotes from Matt Mullenweg before publishing. More in the followup.

Automating Wikipedia History. I started a contest to make a Greasemonkey script to visually browse Wikipedia history, and got some amazing entries, including one by future-jQuery creator John Resig.

Yahoo and Upcoming, Sitting In A Tree. One of the craziest things that ever happened to me, the optimism in this post is almost blinding.

House of Cosbys, Mirrored. After the brilliant Cosby-inspired animated series was shut down, I mirrored all of the videos and got a takedown order from Bill Cosby’s lawyer. I publicly defied it, compiled a list of Cosby parodies in the media, and did an interview about it with the New York Times. I never heard from team Cosby again.

2006

Metafilter Sources 2006. Tracking how the top 50 link sources on Metafilter changed between 2004 and 2006.

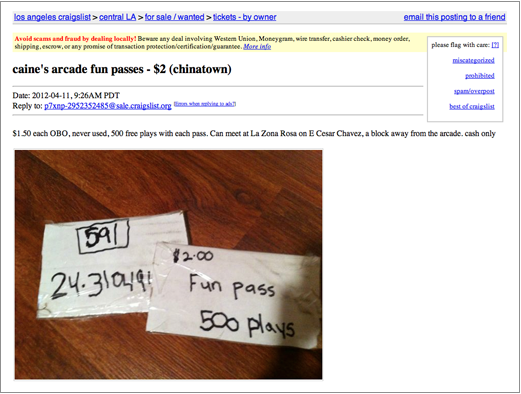

Sex Baiting Prank on Craigslist Affects Hundreds. I broke the story of Jason Fortuny’s “Craigslist Experiment” after seeing a link to it in a private discussion forum. This ended up being a huge story, involving Craigslist, lawsuits, and ruined lives.

2007

Outgoing. Waxy.org went into cryogenic sleep while I was working at Yahoo and raising my baby boy, so I decided to take some time off to write again and explore new ideas.

2008

Colin’s Bear Animation. Four years later, this video still makes me laugh. I tracked down Colin and interviewed him about it.

Personal Ads of the Digerati. I dug up vintage personal ads from Dave Winer and Richard Stallman, and I interviewed RMS about his unusual methods of accessing the web.

The Times (UK) Spamming Social Media Sites. I exposed some nefarious SEO practices from a mainstream newspaper, and interviewed founders of online communities to see what they thought.

Highlights from the British MovieTone Darkweb. Some wonderful vintage videos from a service that doesn’t want you to find them. I’m amazed these videos still work.

ForumWarz Postmortem: Interviewing the Game’s Creators. This innovative game never got popular, but I was very proud of this interview.

WIRED and The WELL. I have a complete archive of The WELL, and occasionally dig into it for research. For anyone who cares about Wired history, it’s a treasure trove.

Internet Power, Volume 1: Flashback to the VHS-Era Web. I set up a VCR and started ripping vintage VHS tapes about the Internet. This was the first of a series of VHS rips, including Internet Power Vol. 2, Olympia School District, and Computability.

Fanboy Supercuts, Obsessive Video Montages. The blog post that named the “supercut” genre, I continued adding to it for years before starting Supercut.org.

Milliways: Infocom’s Unreleased Sequel to Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. This post caused me more pain and heartache than anything I’ve ever written. On its release, I was extremely proud of it, reconstructing the never-before-told history of an unreleased Infocom game using digital archives. But I didn’t ask permission before quoting private emails, causing major fallout on the source that provided me with the archives, ending our friendship forever. You have no idea how often I wish I could unpublish this post.

The Whitburn Project: 120 Years of Music Chart History. I’ve always loved this story about a group of record collectors on Usenet, illegally swapping Billboard chart spreadsheets. In my followup post, I used the data to analyze music history.

The Machine That Changed the World: Great Brains. An awesome, out-of-print documentary series on computer history that I ripped from VHS, and created annotated show notes for each of the five episodes.

Girl Turk: Mechanical Turk Meets Girl Talk’s “Feed the Animals”. The first of my Mechanical Turk experiments, crowdsourcing metadata about the album to make neat charts.

Cheap, Easy Audio Transcription with Mechanical Turk. People still cite this post regularly as the guide for DIY crowdsourced transcription.

Kickstarter. The first of many posts about Kickstarter, when I first met the team and joined the board. “Ultimately, everybody should be able to support themselves doing what they love using the web.”

Memeorandum Colors: Visualizing Political Bias with Greasemonkey. I worked with Joshua Schachter on this Greasemonkey script analyzing linking behavior on Memeorandum. I still use this every day.

The Faces of Mechanical Turk. I wanted to know what they looked like, and was willing to pay them to find out. This image seems to show up in every conference presentation about Mechanical Turk.

2009

Robin Hood’s “Oo De Lally,” Translated Into 16 Languages. This makes me happy.

Translating “The Economist” Behind China’s Great Firewall. One of the strangest online communities I’ve ever discovered, a group of Chinese fans of The Economist translating the entire thing cover-to-cover as a learning tool. I ended up writing a shorter version of this piece for the New York Times.

Attribution and Affiliation on All Things Digital. This investigation into AllThingsD’s linking practices led to concrete change. They never use long quotes anymore, clearly attribute, and drive traffic to the blogs they link to. Everyone wins.

Category Inflation at the Webbys. In the three years since, the number of categories continues to explode. Planning on writing a followup soon.

Kind of Bloop: An 8-Bit Tribute to Miles Davis. My first Kickstarter project was a big success, hitting its goal in four hours, and went on sale later that year.

Meme Scenery. One of my all-time favorite posts, I removed the subjects of famous memes from their backgrounds. There’s something weirdly serene about these background locations without context.

Code Rush in the Creative Commons. In 2008, I’d posted an annotated copy of the classic Mozilla documentary and interviewed the director after he requested I take it offline. A year later, he decided to release it under a Creative Commons license, allowing me to put my annotated version back online.

2010

Interviewing Ted Rall on Comics Journalism in Afghanistan. I interviewed several project creators for the Kickstarter podcast, including this one with author and cartoonist Ted Rall, Pixeljam and James Kochalka, and R.U. Sirius.

Wikileaks Cablegate Reactions Roundup. Sometimes, there’s value in just curating the best set of links around a topic. Every time I’ve ever done this, people seem to like it. I need to remember that more often.

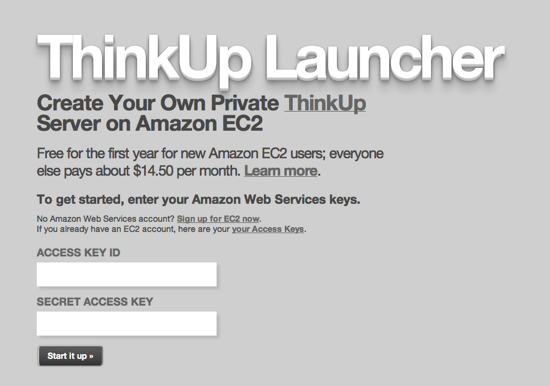

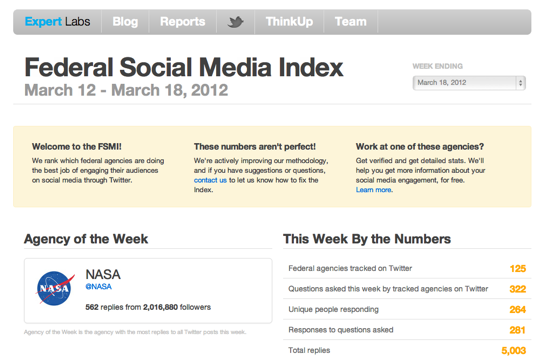

Joining Expert Labs At the end of 2010, I took a leap and joined Expert Labs to work on tools to help government agencies better listen to citizens using social media.

2011

Metagames: Games About Games. Quite possibly the most entertaining research I’ve ever done. It took me forever, largely because I ended up playing so many clever games.

The Daily: Indexed. I got a lot of press for creating a public index of The Daily’s iPad app, against their will. After my trial was up, I wrote about how I did it.

Making Supercut.org. The product of one very, very long night, I worked with artist Michael Bell-Smith to make a script that generated randomized video clips composed entirely of spliced-together supercuts.

Playable Archaeology: An Interview with Telehack’s Anonymous Creator. I was so floored by this tour de force of computing history, I interviewed the brilliant, but anonymous, genius behind it.

Kind of Screwed. The long, frustrating tale of the contested Kind of Bloop artwork, which cost me a large out-of-court settlement and a bunch of legal bills. Makes a good story, though!

Apple’s 1987 Knowledge Navigator, Only One Month Late. As I was watching the Knowledge Navigator video, I started piecing together dates to figure out when it was supposed to take place. I was blown away by the coincidence.

Google Kills Its Other Plus, and How to Bring It Back. My first column for Wired ended up being a big one. Lots of other power users were justifiably upset, and it directly led to the “Verbatim” feature being added to Google Search.

Supercut: Anatomy of a Meme. I dug into the supercut meme using Mechanical Turk and my database of clips. This doubled as the launch announcement for Supercut.org, a community-contributed index of videos.

Google Analytics A Threat to Potential Bloggers. Exposing one of my techniques for researching anonymous sites, I was surprised how many people didn’t know about this.

Viewing the UC Davis Pepper Spraying from Multiple Angles. Sometimes, the simplest ideas are the most powerful. The video’s been viewed on YouTube over 150k times.

No Copyright Intended. Remix culture is the new Prohibition.

I’ll wrap it up there. With luck, I’ll see you in ten more years. Thanks for reading.