Last month, an anonymous blogger popped up on WordPress and Twitter, aiming a giant flamethrower at Mac-friendly writers like John Gruber, Marco Arment and MG Siegler. As he unleashed wave after wave of spittle-flecked rage at “Apple puppets” and “Cupertino douchebags,” I was reminded again of John Gabriel’s theory about the effects of online anonymity.

Out of curiosity, I tried to see who the mystery blogger was.

He was using all the ordinary precautions for hiding his identity — hiding personal info in the domain record, using a different IP address from his other sites, and scrubbing any shared resources from his WordPress install.

Nonetheless, I found his other blog in under a minute — a thoughtful site about technology and local politics, detailing his full name, employer, photo, and family information. He worked for the local government, and if exposed, his anonymous blog could have cost him his job.

I didn’t identify him publicly, but let him quietly know that he wasn’t as anonymous as he thought he was. He stopped blogging that evening, and deleted the blog a week later.

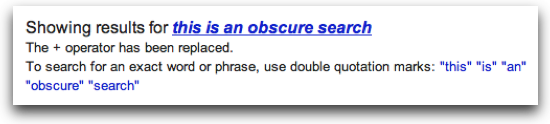

So, how did I do it? The unlucky blogger slipped up and was ratted out by an unlikely source: Google Analytics.

Reverse Lookups

Typically, Google will only reveal a user’s identity with a federal court order, as they did with a Blogger user who harassed a Vogue model in 2009.

But anonymous bloggers are at serious risk of outing themselves, simply by sharing their Google’s Analytics ID across the sites they own.

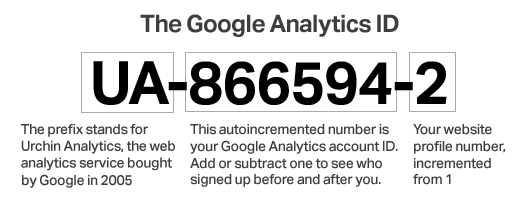

If you’re watching your pageviews, odds are you’re using Google to do it. Launched in 2005, Analytics is the most popular web statistics service online, in use by half of Alexa’s top million domains.

For the last few years, online SEO tools have published Analytics and AdSense IDs for the domains they crawl publicly, typically for competitive intelligence, such as ferreting out your competitor’s other websites.

But in the last year, several free services such as eWhois and Statsie have started offering reverse lookup of Analytics IDs. (Most also allow searching on the Google AdSense ID, though I wasn’t able to find an anonymous blogger sharing an AdSense ID across two sites.)

Finding anonymous bloggers from Analytics is less likely than other methods. It’s still more likely that someone would slip up and leave their personal info in their domain or share a server IP than to share a Google Analytics account. But it’s also more accurate. Hundreds or thousands of people can share an IP address on a single server and domain information can be faked, but a shared Google Analytics is solid evidence that both sites are run by the same person.

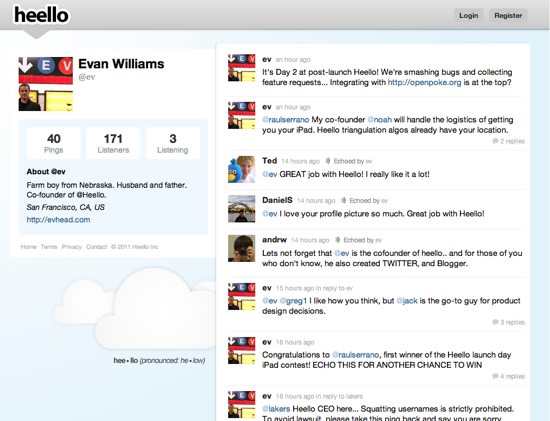

And unlike any other method, it can unmask people using hosted blogging services. Tumblr, Typepad and Blogger all have built-in support for Google Analytics, though reverse lookup services haven’t comprehensively indexed them. (Note that WordPress.com doesn’t support Analytics or custom Javascript, so their users aren’t affected.)

Just to be clear, this technique isn’t new. The first Google Analytics reverse lookup services started in 2009, so the technique’s been possible for at least two years. My concern is that it isn’t nearly well-known enough. It’s not mentioned in any guide to anonymous blogging I could find and several established bloggers, engineers, and entrepreneurs I spoke to were unaware of it.

Unmasking an anti-Mac blogger may not be life-changing, but if you’re an anonymous blogger writing about Chinese censorship or Mexican drug cartels, the consequences could be dire.

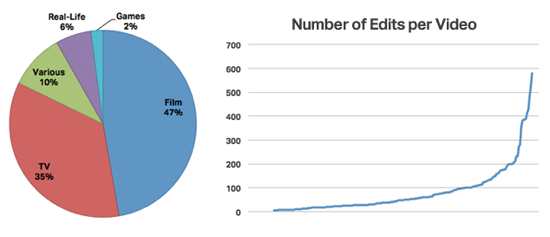

I decided to see how pervasive this problem is. Using a sample of 50 anonymous blogs pulled from discussion forums and Google news, only 14 were using Google Analytics, much less than the average. Half of those, about 15% of the total, were sharing an analytics ID with one or more other domains.

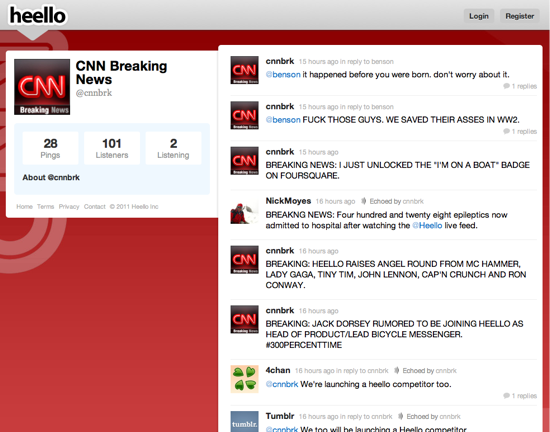

In about 30 minutes of searching, using only Google and eWhois, I was able to discover the identities of seven of the anonymous or pseudonymous bloggers, and in two cases, their employers. One blog about Anonymous’ hacking operations could easily be tracked to the founder’s consulting firm, while another tracking Mexican cartels was tied to a second domain with the name and address of a San Diego man.

I’ve contacted each to let them know their potential exposure.

Protecting Yourself

Some of the most important and vital voices online are anonymous, and it’s important to understand how you’re exposed. Forgetting any of these can lead to lawsuits, firings, or even death.

If you’re aware of the problem, it’s very easy to avoid getting discovered this way. Here are my recommendations for making sure you stay anonymous.

- Don’t use Google Analytics or any other third-party embed system. If you have to, create a new account with an anonymous email. At the very least, create a separate Analytics account to track the new domain. (From the “My Analytics Accounts” dropdown, select “Create New Account.”)

- Turn on domain privacy with your registrar. Better, use a hosted service to avoid domain payments entirely.

- If you’re hosting your own blog, don’t share IP addresses with any of your existing websites. Ideally, use a completely different host; it’s easy to discover sites on neighboring IPs.

- Watch your history. Sites like Whois Source track your history of domain and nameserver changes permanently, and Archive.org may archive old versions of your site. Being the first person to follow your anonymous Twitter account or promote the link could also be a giveaway.

- Is your anonymity a life-or-death situation? Be aware that any service you use, including your own ISP, could be forced to reveal your IP address and account details under a court order. Use shared computers and an anonymous proxy or Tor when blogging to mask your IP address. Here’s a good guide.

Stay safe.