This Friday, I’ll be speaking at the Webvisions conference in Portland about Internet memes, how they spread, and how their distribution’s changed over time.

As part of that research, I’ve been digging into my original server logs from the Star Wars Kid debacle, five years after I played a major role in what some say is the biggest viral video of all-time.

Be warned, this is more detail than you’ll ever want about the origins of the Star Wars Kid meme and how it spread. You don’t care about this level of detail, but I’m writing this all down so that I never have to think about it again.

In addition, I’ve decided to release the first six months of server logs from the meme’s spread into the public domain — with dates, times, IP addresses, user agents, and referer information. (Download it below.)

Early Origins

Like I mentioned in my original entry, the video was first released by Ghyslain’s schoolmates to Kazaa on April 19, 2003 with the original filename “ghyslain_razaa.wmv.” Within three days, it was being passed around in the offices of Raven Software in Madison, Wisconsin, where a game developer named Bryan Dube posted it on his personal website on April 22. Two days later, he created the first Star Wars Kid remix, adding lightsabers and sound effects in a new video titled “TheLastHope.avi.”

On April 27, a mostly-NSFW online community called Sensible Erection linked to the video on Bryan’s website. Later that evening, an SE user cross-posted it to a private file-sharing community I belong to with the new filename “star_wars_guy.wmv.” It quickly became the most popular file on the site, which is where I found it the following day, April 28 at 7:52pm.

On April 29, I renamed it Star_Wars_Kid.wmv and posted it to my site at 4:49pm — inadvertently giving the meme its permanent name. (Yes, I coined the term “Star Wars Kid.” It’s strange to think it would’ve been “Star Wars Guy” if I was any lazier.) An hour later, Scott Gowell becomes the first person to link to the video.

From there, for the first week, it spread quickly through news site, blogs and message boards, mostly oriented around technology, gaming, and movies. Throughout the life of the meme, most of the referers are blank, suggesting people were primarily sending the links by email or instant message.

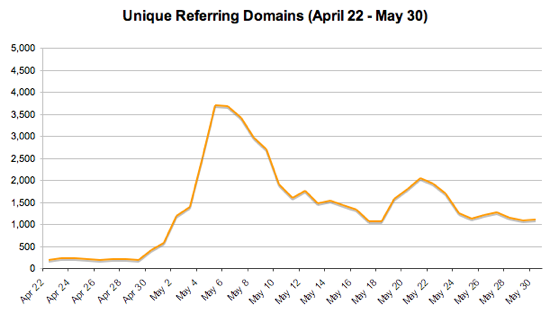

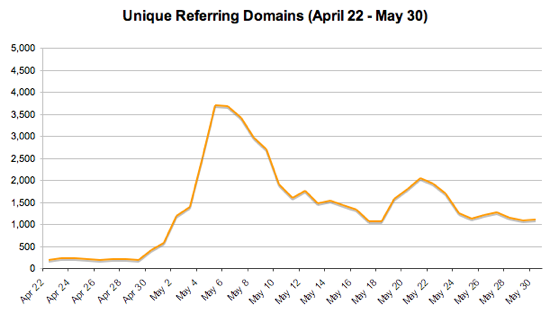

The chart below shows the distinct top-level domains that appeared in the referral logs grouped by day.

It’s worth noting that the majority of sites sent less than 10 referers in that first month, and 21% of domains referred only one user. (Note: The chart below is on a logarithmic scale for both axes.)

Mainstream News Coverage

Here’s some of the highlights from the mainstream media coverage. The New York Times was the first major paper to report on it, almost a week after I tracked Ghyslain down, Jish and I interviewed him for the first time, and we started the fundraiser.

May 19, New York Times

May 19, Wired News

May 20, Public Radio International’s “The World” (radio program)

May 20, Globe and Mail

May 20, National Post

May 23, The Mirror UK

Jun 6, LA Times

Jul 4, The Independent UK

Jul 12, The Age

Jul 23, Wired News

Jul 25, BBC News

Jul 31, NPR w/Tavis Smiley (radio interview)

Aug 21, USA Today, syndicated Associated Press article

Aug 25, NBC’s Today Show (TV program)

Aug 26, MSNBC’s Countdown (TV program)

Aug 28, USA Today

Aug 30, Seattle P-I

Sep 8, SF Chronicle

Sep 15, Variety

Sep 16, Globe and Mail

Nov 18, CBS Evening News

Statistics

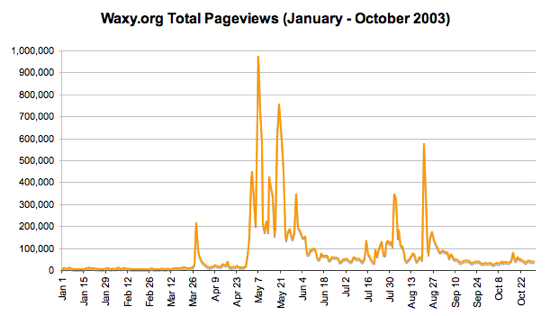

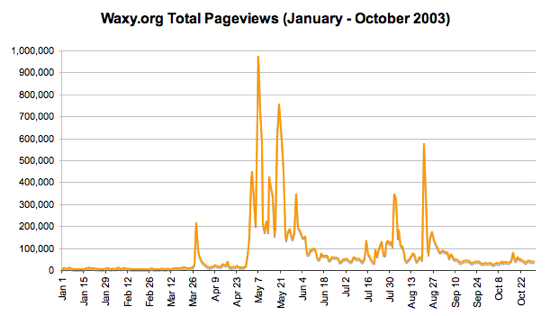

Here’s what the Star Wars Kid meme did to my overall traffic. At its peak, I received almost a million pageviews in a single day.

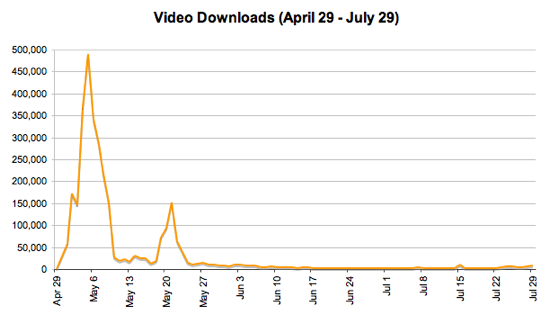

That includes all pageviews on my weblog entries. Isolating only the video downloads from my site, or later redirected to one of the mirrors, gives the following chart.

Download the Data

This file is a subset of the Apache server logs from April 10 to November 26, 2003. It contains every request for my homepage, the original video, the remix video, the mirror redirector script, the donations spreadsheet, and the seven blog entries I made related to Star Wars Kid. I included a couple weeks of activity before I posted the videos so you can determine the baseline traffic I normally received to my homepage.

The file is 158 megabytes — 1.6GB uncompressed — so I’m distributing it with BitTorrent. The data is public domain. If you use it for anything, please drop me a note!

Download: star_wars_kid_logs.zip.torrent