So, Yahoo’s finally decided to close Upcoming.org, the events community I started nearly ten years ago. And, in Yahoo’s typical fuck-off-and-die style, they’re doing it with 11 days notice, no on-site announcement, and no way to back up past events.

I knew its closure was inevitable after the infamous sunset slide, but never knew when it would happen. Like a newspaper prepping for a sick celebrity, this obituary’s been sitting in my drafts folder for months, waiting for its sad publication day.

The last five years were hard on Upcoming. After Gordon Luk, Leonard Lin, and I left at the end of 2007, the site quickly started to fall apart. The social features that made Upcoming unique were minimized, or removed entirely, by a series of redesigns. Spam, like creeping kudzu, was left unchecked and spread across the site. Fortunately, the final catastrophic redesign never made its way out of beta.

By 2009, the only people using Upcoming were event promoters and spammers. (Especially depressing considering self-promotion was banned entirely for its first two years.)

Frustratingly, nothing’s come to take its place. Potential competitors like Plancast and Going closed their doors, while others never grew an organic community. Some sites carved off a piece of Upcoming: Facebook’s private events, Songkick’s concerts, and Lanyrd’s fantastic conference coverage.

But, for me, finding events I care about feels like 2002 again. I’m missing geeky events I’d love, and when I travel to a new city, I’m back to digging through the calendar listings of my local weekly newspapers. It blows my mind that the problem Upcoming solved — surfacing interesting events in a city, driven by public social activity — is an unsolved problem again.

And now, Yahoo will quietly take Upcoming off life support, an opportunity squandered.

Bleeding Purple

It’s hard to believe now, but there was a time when Yahoo was actually pretty cool, in its own dorky Silicon Valley way.

By 2005, when we started talking to Yahoo, they’d made a series of thoughtful hires, including PHP creator Rasmus Lerdorf, Jeremy Zawodny, Tom Coates, Simon Willison, and future Etsy CEO Chad Dickerson. Cameron Marlow, Jeffery Bennett, and Mor Namaan were doing pioneering work at Yahoo Research. They acquired Flickr, bringing some of the most talented and creative people in technology to help change the company from the inside, including Cal Henderson, Heather Champ, and founders Caterina Fake and Stewart Butterfield. A month after we came in, they acquired Del.icio.us.

Clueful people were making their way up to the executive level, too. Future Bandcamp founder Ethan Diamond led the redesign of Yahoo Mail, future Topspin CEO Ian Rogers was managing Yahoo Music, and and Bradley Horowitz, now VP of Product at Google, was taking over big pieces of the company. Yahoo was an exciting place to be.

Upcoming was a side project, created during my day job at a financial company. After my son was born, I had no time to work on Upcoming at all, even as the community grew. Spammers started to discover the site, as bug reports and support requests piled up unanswered. The opportunity to work on my own project full-time was a dream come true.

And Yahoo seemed like a perfect home for Upcoming — they’d promised resources to grow the community, we’d get to work at a promising tech giant with some of our favorite people, and the acquisition price was small but seemed fair. Coming into Yahoo, we were hopeful.

It wasn’t clear how dysfunctional the rest of Yahoo was until we’d settled in, and there was no indication how horrible they’d soon become in the years to follow. This was long before they gave up dissidents to the Chinese government, closed Geocities, weaponized their patents, “sunsetted” Delicious, and a number of other awful decisions.

In hindsight, selling Upcoming to Yahoo was a horrible mistake. Selling your company always means sacrificing control and risking its fate, and as we now know, online communities almost always fail after acquisition. (YouTube is the rare exception, albeit one with billion-dollar momentum.) But Yahoo was a particularly horrible steward for the community.

I built Upcoming because it scratched a personal itch, and I was delighted when so many others found it useful. For the small group of old-schoolers that remember it in its prime, Upcoming made their lives better. I’ve heard stories of people finding friends and spouses through Upcoming, people lonely in a new city tapping into new communities, impromptu parties gaining momentum.

I’m going to miss it.

Archiving Upcoming

Upcoming stopped being relevant long ago, and part of me is happy that Yahoo’s putting this bastardized version of the site out of its misery. (In case your memory’s foggy, compare how it looked when we left to its current state.)

What really upsets me is that the archived events will soon be taken offline, and with no way to back it up. Ten years of history will be gone in 11 days. Good URLs never die, and I’m frustrated that every link to Upcoming will soon 404.

I’ve reached out to Yahoo multiple times over the last few months about re-acquiring the Upcoming.org domain and event database, but they were less than receptive.

I would love to create a permanent archive of Upcoming, with a clean responsive layout and some month-by-month analysis and visualization of the site’s history, but getting the metadata’s proving much more difficult than I thought.

All of Upcoming’s events and venues use autoincremented ids, making it dead simple to generate a list of URLs to scrape. But Yahoo’s security makes scraping a challenge. Every time I’ve tried to back up pages, I can only grab a few files with curl or httrack before Yahoo starts serving blank responses.

Note that scraping the HTML alone won’t provide the full list of attendees for popular events, which are displayed via Javascript. For example, to get all the metadata for this event, you’d need to scrape both the event page for the event details and this XML for the attendees.

If you have any idea how to scrape Upcoming’s events, or can get me a dump in any form, please get in touch ASAP. Anonymity guaranteed.

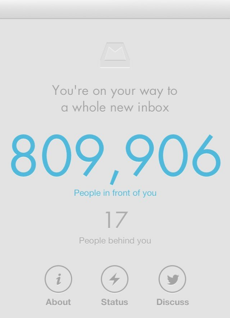

Update: Archive Team is working to save Upcoming, and they need your help in the rescue efforts.