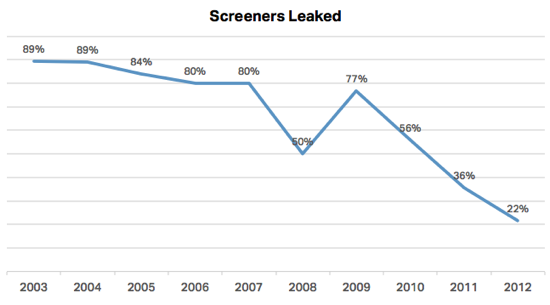

Every year, the MPAA tries desperately to stop Oscar screeners — the review copies sent to Academy voters — from leaking online. And every year, teenage boys battling for street cred always seem to defeat whatever obstacles Hollywood throws at them.

For the last 10 years, I’ve tracked the online distribution of Oscar-nominated films, going back to 2003. Using a number of sources (see below for methodology), I’ve compiled a massive spreadsheet, now updated to include 310 films.

This year, for the first time, I’m calling it: after three years of declines, the MPAA seems to be winning the battle to stop screener leaks. But why?

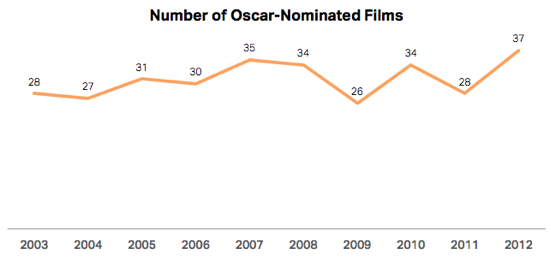

A record 37 films were nominated this year, and the studios sent out screeners for all but four of them. But, so far, only eight of those 33 screeners have leaked online, a record low that continues the downward trend from last year.

(Disclaimer: Any of this could change before the Oscar ceremony, and I’ll keep the data updated until then.)

They may be winning the battle, but they’ve lost the war.

While screeners declined in popularity, 34 of the nominated films (92 percent) were leaked online by nomination day, with 25 of them available as high-quality DVD or Blu-ray rips. Only three films — Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, My Week with Marilyn and W.E. — haven’t leaked online in any form (yet!).

If the goal of blocking leaks is to keep the films off the internet, then the MPAA still has a long way to go.

There are a number of theories about what’s causing the decline.

It could be attributed to tighter controls — personalized watermarks, the aggressive prosecution of leakers, and greater awareness of the risks for Academy voters.

But the MPAA may have little to do with the decline. Oscar-nominated films could be coming out earlier in the year, making screeners less important.

Or maybe the interests between the mainstream downloader and industry favorites is diverging? If the Oscars are mostly arthouse fare and critical darlings, but with low gross receipts, they’ll be less desirable to leak online. It would be very interesting to track the historical box office performance of nominees to see how it affects downloading. (Maybe next year!)

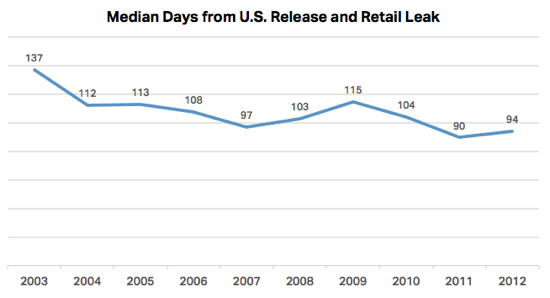

The continuously shrinking window between theatrical and retail releases may be to blame. After all, once the retail Blu-ray or DVD is released, there’s no reason for pirate groups to release a lower-quality watermarked screener.

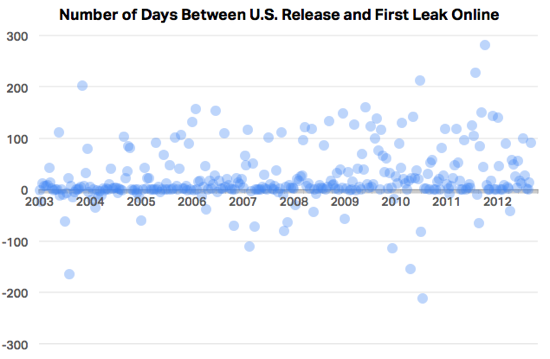

The chart below tracks the window between U.S. release and its first DVD/Blu-Ray leak online, which shows how the window between theatrical and retail release dates is slowly closing since 2003.

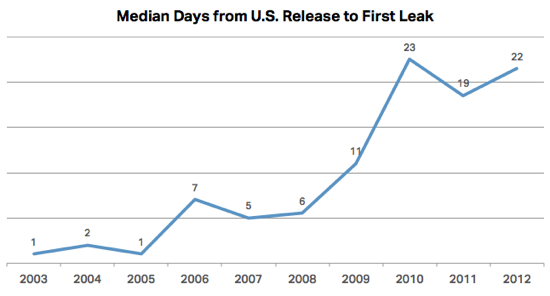

Whatever the reason, online movie releasing groups are taking longer to pirate movies than ever. When I first started tracking releases in the early- to mid-2000s, the median time between theatrical release to its first leak online was 1 to 2 days. Now, that number’s crept up to over three weeks.

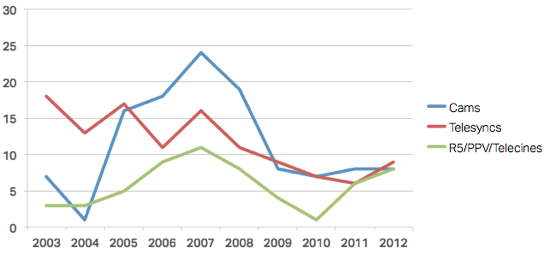

The rise in leak time correlates with a dip in popularity for lower-quality sources, like camcorder-sourced footage. This year, only eight of the 37 nominees (21 percent) were sourced from camcorder footage. (This is likely because there are fewer blockbuster nominees than in the mid-2000s.)

As the industry slowly transitions from physical media to streaming video, it’ll be interesting to see if the downward trend continues, or if the ease of capturing streaming video spawns a new renaissance for screeners. Last year, Fox Searchlight distributed screeners with iTunes, and all were quickly and easily pirated.

The Data Dump

Skeptical of my results? Want to dig into it yourself? Good! Here’s the complete dataset, available on Google Spreadsheets or downloadable as an Excel spreadsheet or comma-separated text file.

Methodology

I include the full-length feature films in every category except documentary and foreign films (even music, makeup, and costume design).

I use Yahoo! Movies for the release dates, always using the first available U.S. date, even if it was a limited release, falling back to the first available U.S. date in IMDB.

All the cam, telesync, and screener leak dates are taken from VCD Quality, supplemented by dates in ORLYDB. I always use the first leak date, excluding unviewable or incomplete nuked releases.

The official screener release dates are from Academy member Ken Rudolph, who kindly lists the dates he receives each screener on his personal homepage. Thanks again, Ken!

For previous years, see 2004, 2005, 2007, 2008 (part 1 and part 2), 2009, 2010, and 2011.