Telehack is the most interesting game I’ve played in the last year… a game that most users won’t realize is a game at all.

It’s a tour de force hack — an interactive pastiche of 1980s computer history, tying together public archives of Usenet newsgroups, BBS textfiles, software archives, and historical computer networks into a multiplayer adventure game.

Among its features:

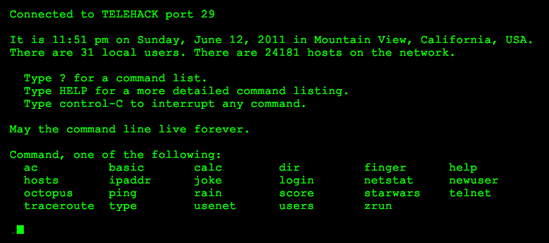

- Connect to over 24,000 simulated hosts, with logged-in ghost users with historically-accurate names culled from UUCP network maps.

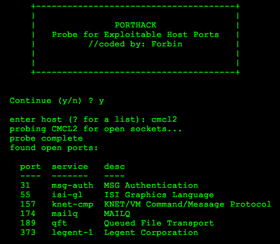

- Hacking metagames, using simplified wardialers and rootkit tools.

- User classes that act as an achievements system.

- Group chat with

relay, and one-on-one chat withsendortalk. - Reconstructed Usenet archives, including the Wiseman collection.

- A BASIC interpreter with historical programs from the SIMTEL archives.

- Standalone playable games, including Rogue and a Z-code interpreter for text adventure games like Adventure and Zork.

- Hidden hosts and programs, discoverable only by hacking Telehack itself.

The entire project was engineered by “Forbin,” an anonymous Silicon Valley engineer named after the protagonist of Colossus: The Forbin Project. Like the chief engineer of the film, Forbin’s created a networked supercomputer that defies all expectations. (Hopefully it won’t gain sentience and enslave the human race.)

I had to know more. With the help of Paul Ford, I interviewed Forbin about the project — using Telehack’s send utility, naturally. Read on for the full interview about his motivations, how it’s built, and why he’s chosen to remain anonymous.

Andy Baio: So, first off, I want to tell you how much I’m in love with Telehack. You’ve made something truly unique… I’d love to hear about your inspiration for building it.

Forbin: Thank you. I’m glad that people are enjoying it. The inspiration was my son. I had shown him the old movies Hackers, Wargames, and Colossus: The Forbin Project and he really liked them. After seeing Hackers and Wargames, he really wanted to start hacking stuff on his own.

I’d taught him some programming, but I didn’t want him doing any actual hacking, so I decided to make a simulation so he could telnet to hosts, hack them, and get the feel of it, but safely.

What did he think?

He really liked it. At first he thought it was all real, and he was actually hacking into government computers and such. It was great. Eventually though, like Santa Claus, he figured out he wasn’t really wardialing all those systems.

He’s been my best beta-tester. 🙂

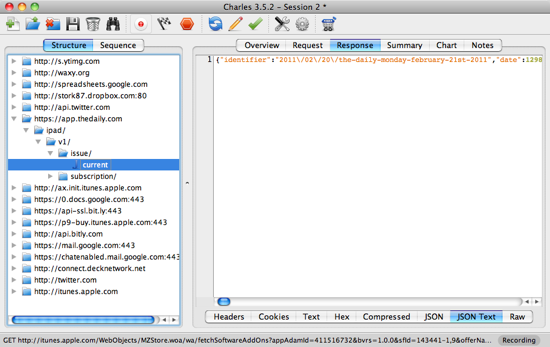

Hacking a host on Telehack

When do you think he’ll be ready for real-world hacking? Is there a path to graduation from Telehack?

Telehack can help you learn commandline basics. I’ve told him not to ever enter any real systems without permission.

I’m curious if you’ve played Digital: A Love Story. It seems like Christine Love was trying to do something similar — conjuring an earlier time in computing history, but without worrying too much about historical accuracy.

I played a bit of Digital: A Love Story. I thought it was wonderful. I really liked the atmosphere it evoked. That was the same effect I was going for in Telehack, but in a different way. Silent, no sound… Just green text and more code, but the same emotion.

Regarding historical accuracy, one of the surprising things about Telehack is how those old systems were hard to use. Whenever a movie or a book looks back at the past, it can look through a set of lenses that make the past seem more engaging and accessible, and sometimes add a narrative. Someone on Hacker News referred to Telehack as “MovieOS,” and that’s exactly right.

There are actual TOPS-10 systems on the net you can get accounts on. They’re not easy to get into. I wanted to reduce the usability barriers to the old commandline interfaces, while giving the same feel of the systems, and blend some of the good things I remembered from various systems together.

Telehack seems to borrow quite a bit from modern videogame theory… Integrated tutorials, slowly ramping up difficulty, multiple avenues to exploration without a linear path. Paul Ford suspected you’re a game designer.

I have done some computer games, although that is not my profession. I really admire the advances that have occurred in game design, although I’m not much of a gamer myself. Mostly, I wanted to help newcomers get across barriers of accessibility which is what the old tutorial manuals were all about.

Read an old DECsystem-20 manual. It tells you, in excruciating detail, how to type control-C to interrupt a program. It turns out people still need to know that but aren’t being told anymore.

The other part is that the system is open-ended. It has all this old code that is animated by resurrecting an interpreter for a dead language. People can run programs again that haven’t been run — and experienced — for 20 years. And see old files through a lens that makes them look like they used to. That’s fun.

Speaking of old files, the way you used the textfiles.com and Usenet archives feels brand new. You’ve created a playful environment for exploring archival material in a new way. It made me wonder what other data sources could be reinvented by making them game-like.

What Jason Scott did with textfiles.com is heroic. He’s saving away all this stuff that is completely unique, and irretrievable otherwise. But to make people want to see it, byte by byte, I thought it would be neat to offer it up, a piece at a time, in a format similar to how the files were originally experienced.

You dial some modem number — not busy! It actually connects and then you see what files they have and download some of them. Most of them are crazy stuff but period-relevant. So it’s a way to animate old text files.

Same thing with the Usenet archive, although my Usenet reader needs some work. It’s pretty crufty. There is so much in there, I haven’t really found a good way to get people back into it yet.

Folks would wait in anticipation for Usenet — the daily poll — where your modem would call some hub and get you the news. I have to find some way to bring that back to the archive.

Google Groups doesn’t give that feeling. Neither does Telehack’s usenet command currently. Still noodling on that.

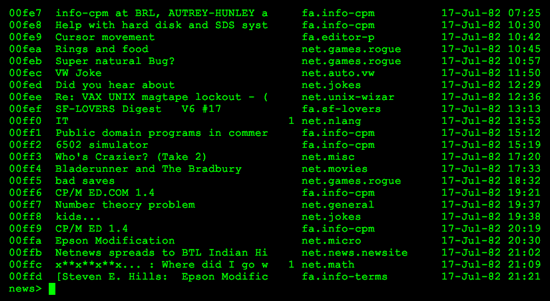

Reading Usenet posts from 1982

Does it advance in real-time? Are you adding “new” articles to the archive in a rolling period?

No, although that’s a good idea for a way for it to be more dynamic and engaging.

You’ve been adding features incrementally since you launched it, but how long did it initially take you to build from conception?

If you type uptime, it says sysgen was 454d ago at 07-Mar-10 20:26:00. That’s when I started working on it. Not full-time, there were months when I didn’t have any time to work on it. It’s mostly been a small side project.

What was the hardest thing to get right?

There is one feature that works in the telnet interface, but not in the http client yet — the baud rate simulation. If you dial or wardial into a host and you’re connected to Telehack with telnet, it will actually give you a 2400 or 9600 or whatever connection, but that doesn’t work on the html interface yet sadly.

It’s not the same when you dial into a host and the text renders instantly. For the full authentic feel, you should have to wait for the lines to appear slowly, as we once did. 🙂

I keep my 300 baud VicModem on my desk as a reminder of how good we have it now.

300 baud was really slow! I started there too, with a Hayes on an Apple II. Type baud 300 on Telehack, it’s hard to see how we could use those systems, but we did. They were amazing, even at that speed.

I’d love to hear more about the technology behind it.

Telehack is built in Perl, in a single process, in an epoll-driven event loop. There are two interpreters — Z-code, which is an interpreter called Rezrov in CPAN, and a BASIC interpreter, which I wrote. Currently it doesn’t fork any external code. Various functions, including the 6502/VAX CPU and such, are simulated.

Any plans to open-source any of it? I’m sure some of the community would love to hack on Telehack, to extend it in different directions.

Yes, I plan to open it up at some point.

So, I have to ask: why the anonymity? The mystery definitely adds to the fun, but most people would love to take credit for such an impressive project.

Well, I have a day job, and I didn’t want this to be a distraction. I also made this for my kid, but didn’t really want to expose him to a larger internet just yet.

Are you worried that coming out from behind the curtain will bring attention to him too? I’m the parent of a six-year-old, and can definitely appreciate that.

At an earlier point in my career, I got a lot of press for a project I did. The intense interest from that made me very cautious about what I put online. I took down my personal photos and such. I would be sad if I felt like I had to take down Telehack.

Makes sense. What have you thought about the reaction? Like several others, when I first saw Telehack, I completely underestimated its depth. It seems like an deep rabbit hole that endlessly rewards curiosity.

I’m extremely happy that people are enjoying it. I was a bit sad that some commenters initially dismissed it as a simple JS shell. It was pretty cool when the first person found ptycon and the secret entry points in the system monitor.

With zero fans, I’d be pretty disappointed. With any n > 0, I’m happy. I don’t expect it’s a huge audience though. Doesn’t have to be. It’s an artistic/historical project to me.

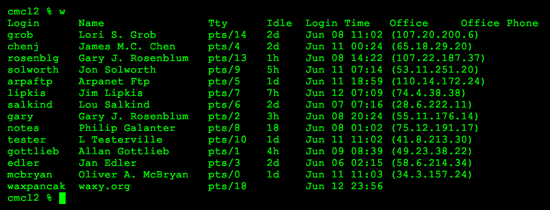

Viewing users on NYU’s cmcl2 network circa 1988, and me.

You’ve done some incredible data archaeology here — reconstructing 25,000 hosts from the early Internet, along with the people that used them at the time. One guy on Hacker News was able to find himself and his two best friends at the time logged into the host he first used when he get online. How did you do it?

Well, a lot of this information is available online, but you need to look at the right way to interpret it.

Were you able to find yourself in the archives?

Yup, I’m in there.

Any specific rules for how you scattered the text and game files across hosts?

There is some topic-clustering for the text files, the rest is mostly random. But I’m still working on the game parts of this thing.

If Telehack ever takes off, would you ever consider doing it for a living? I have no idea what you do for a living, but I can’t help but think you’ve missed your true calling as a game designer.

Well, thank you for that. 🙂 I’ll have to get back to you on that. At this point, I’m mostly interested in fleshing it out, so I’m happy with it.

Telehack’s a pastiche of many different systems, networks, and tools from the mid- to late-1980s. It’s rich with nostalgia. Is there anything you miss from that era?

Good question. The commandline was a universal language. You had to learn it, there was a curve, but it wasn’t that hard. Heck, we were all being taught it in the new classes in middle school. But the GUI’s mission was to kill it.

My worry is that the CLI was symbolic, algebraic, whereas the GUI is… pictorial, or one-step, or something.

hosts | grep foo

It’s important that you understand that. If you’re graduating from any university today, it’s an algebra more important than… uh, algebra, maybe.

I actually don’t miss anything from that era. But I want the best of what was known then to propagate today.