Update: GoldieBlox removed the original video and posted a public apology. See below for updates.

Everyone thinks they know how copyright works, and everyone’s usually wrong. Who can blame them? It’s often counterintuitive, inconsistent, and riddled with grey areas and edge cases.

And no area of copyright law is more confusing than fair use, deliberately designed to be judged in court on a case-by-case basis without any “bright line” tests to guide the way.

The test for fair use is a balancing act of four factors, but how they’re weighed is often subjective, determined by a judge. Different judges rule differently on similar fair use cases, and circuit courts commonly reverse fair use rulings from district courts on appeal.

If even judges can’t agree on fair use, what chance do the rest of us have of understanding it?

In fair use, there’s no silver bullet and exceptions are the norm. Some parodies are fair use, others aren’t. Commercial use can weigh against a fair use ruling, but there are many notable commercial exceptions. Using a substantial amount of the original artwork can hurt your case, other times it doesn’t matter. Damaging the market value of an original artwork can hurt your claim or, as with parodies, it may not matter at all.

So, how does that play out in GoldieBlox v. Beastie Boys?

It’s entirely possible that the GoldieBlox video is simultaneously:

- A parody

- An advertisement

- A derivative of the Beastie Boys’ copyrighted work

- A violation of MCA’s dying wishes

- And, yet, perfectly legal under the fair use doctrine.

Only a judge can decide whether GoldieBlox’s parody is fair use. And, until they do and all the appeals are closed, none of us will know.

In the meantime, let’s bust some myths!

Disclaimer: Hey, I’m not a lawyer either. But I’ve been writing about copyright here for over ten years and dealt with several copyright disputes myself, including my tangle with fair use from Kind of Bloop. I’m going to try to avoid any conjecture here, and stick to actual case law. If I miss something, please let me know.

Myth: The Beastie Boys sued GoldieBlox.

The Beastie Boys were quick to debunk this one themselves in their open letter. “When we tried to simply ask how and why our song ‘Girls’ had been used in your ad without our permission,” they wrote, “YOU sued US.”

But GoldieBlox filed a very particular type of lawsuit, a declaratory judgement. Unlike typical lawsuits, GoldieBlox isn’t seeking damages. They’re asking the court to issue an opinion without ordering Beastie Boys to do anything in particular or pay damages, beyond possibly their own legal expenses.

This appears confusingly aggressive, but it’s a common tactic when threatened with a copyright lawsuit. If it works, the court’s clarification can save the time and money spent fighting an expensive trial. You may remember Robin Thicke reluctantly suing Marvin Gaye’s family, when they threatened to take him to court over “Blurred Lines.” Same deal.

Update: Yesterday, on December 10, the Beastie Boys filed a countersuit. So now they actually are suing GoldieBlox.

Myth: It’s an advertisement, so it’s not fair use.

More than any other, I’ve seen this myth repeated everywhere. Can a company parody a famous artist’s work and use it, against their will, to advertise an unrelated product? Actually, yes, as long as the use is transformative enough.

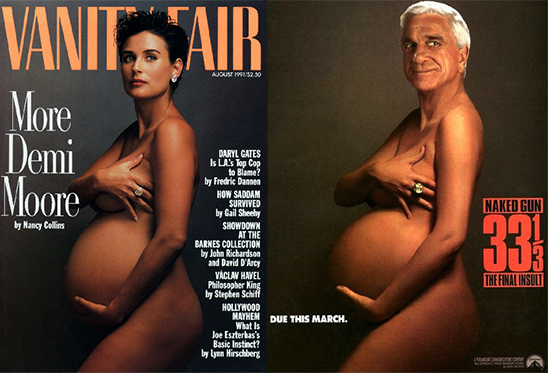

The most famous case is the Naked Gun advertisement below, a parody of photographer Annie Leibovitz’s famous portrait of Demi Moore for Vanity Fair.

If you care about this sort of thing, the District Court’s decision is a fantastic, and surprisingly readable, breakdown of the history of parody and fair use.

In her decision, Judge Preska noted that the landmark 2 Live Crew case, settled by the Supreme Court only two years earlier, set a new precedent for deciding fair use cases.

In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that commercial use does not preclude a finding of fair use, so long as the work is “transformative” — does it add value to the original material and use it for a different purpose, such as criticism or parody?

Delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court, Justice Souter wrote, “The goal of copyright, to promote science and the arts, is generally furthered by the creation of transformative works… The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”

Later in the ruling, Justice Souter specifically addressed parodies in advertising. He wrote, “The use, for example, of a copyrighted work to advertise a product, even in a parody, will be entitled to less indulgence under the first factor of the fair use enquiry, than the sale of a parody for its own sake.”

In the Naked Gun case, armed with this new precedent, the District Court decided in Paramount Pictures’ favor:

“I can only reconcile these disparate elements by returning to the core purpose of copyright: to foster the creation and dissemination of the greatest number of creative works. The end result of the Nielsen ad parodying the Moore photograph is that the public now has before it two works, vastly different in appeal and nature, where before there was only one.”

Annie Leibovitz appealed, but the 2nd Circuit Court affirmed the decision, saying, “On balance, the strong parodic nature of the ad tips the first factor significantly toward fair use, even after making some discount for the fact that it promotes a commercial product.”

So, in the GoldieBlox case, the court will decide whether the parody’s criticism of “Girls” sexist lyrics outweigh its commercial nature. The EFF believes they will, and given the existing precedent, they may be right.

Myth: GoldieBlox stole from the Beastie Boys.

First off, infringement is not theft. These are two completely different terms with different meanings. If GoldieBlox stole something, the Beastie Boys wouldn’t have it anymore.

Second, it’s worth noting that GoldieBlox didn’t sample from the original song. (If they had, this would be a very different lawsuit.) Their parody was recorded with new instrumentation, vocals, and lyrics.

GoldieBlox used the composition to create a derivative work. Because it was unlicensed and created without permission, that new work may infringe the Beastie Boys’ copyright. This lawsuit will determine whether it’s infringement or fair use.

But however you look at it, it’s not stealing.

Myth: The Beastie Boys always have a right to decide how their music is used.

Usually, but not always! The Copyright Act grants broad exclusive rights to musicians to control the reproduction, performance, and distribution of their work for an absurdly long time—70 years after their death.

But there are a number of exceptions. Musicians can’t, for example, stop the secondhand sale of their albums or stop people from covering their songs.

Similarly, fair use is an exception to those exclusive rights. If someone can defend their use of a song in court, and the court rules it a fair use, then that use is legal and outside the artist’s control.

Myth: Adam Yauch’s will forbids using his songs in advertising, so it’s illegal.

In his last will, MCA stated that “in no event may my image or name or any music or any artistic property created by me be used for advertising purposes.”

By ignoring the last wishes of one of hip-hop’s greatest musicians, less than two years after his death, there’s a strong argument to be made that what GoldieBlox is doing is unethical. To me, it feels crass and insensitive.

But is it illegal? Not if the court finds the parody to be fair use.

This isn’t a moral judgement, and this isn’t copyright activism. This is the law, as it exists right now.

Myth: If this is legal, then any company can parody songs in ads for free.

The crux of this case is whether the GoldieBlox parody is transformative. The parody video’s new lyrics criticize the misogynistic lyrics of the original Beastie Boys song. If it didn’t, there wouldn’t be a case.

Any other parody in advertising that doesn’t transform the original will still need permission and pay licensing fees. Snuggie will still have to pay for their version of the Macarena because it doesn’t comment or criticize the original in any way.

It’s worth noting that this isn’t the first time GoldieBlox used a song in an ad. This earlier ad from July rewrote some of the chorus to Queen’s “We Are the Champions”, but left most of it intact. I’d wager they never licensed this music either, and wouldn’t really have a defense if EMI came knocking.

Undetermined: The Beastie Boys were just asking questions and GoldieBlox sued them.

Neither party has released the initial complaint letter from the Beastie Boys, so we don’t know who sent the letters, the tone of the questions or what, if anything, they were demanding.

We do know that GoldieBlox claims in their lawsuit that they were contacted by “lawyers for the Beastie Boys” and the letter claimed that the video is “a copyright infringement, is not a fair use, and that GoldieBlox’s unauthorized use of the Beastie Boys intellectual property is a ‘big problem’ that has a ‘very significant impact.'”

It’s possible that GoldieBlox’s legal team is lying in a court filing, but it seems unlikely. More likely, the truth is somewhere in the middle. The law firm representing the Beastie Boys contacted GoldieBlox, asking for details and pushing them to delete the video. GoldieBlox felt they were in the right, and filed the request for declaratory judgment to find out.

I hope either party releases the original correspondence, it should be interesting.

Undetermined: This is all a publicity stunt.

It could be. GoldieBlox founder and CEO Debra Sterling, despite her Stanford engineering background, spent seven years as a brand strategist and marketing director before starting GoldieBlox. She definitely knows how to get publicity for her projects.

But there are certainly more affordable, less risky ways to gain publicity than filing a lawsuit. If they felt it wasn’t a serious threat, they could have simply gone public with the legal threat, posting the correspondence and writing a blog post.

But there’s no question this lawsuit has raised the profile of GoldieBlox, for better or worse.

The More You Know

So, who knows? This could go either way, and should be a fascinating case to watch. I’m in favor of more case law in either direction, helping draw the lines for what artists can or can’t do. It can be agonizing to make something that skirts the grey areas of copyright law without knowing whether you’re going to end up bankrupt.

Want to learn more?

Both the 2 Live Crew and Annie Leibovitz rulings are surprisingly readable explanations of how copyright and fair use are interpreted by the courts.

On the Media’s PJ Vogt published a great interview with Julie Ahrens, the director of Copyright & Fair Use at Stanford’s Center for Internet & Society. The EFF’s legal analysis is interesting, but I think they downplay the advertising issue too much. Rachel Sklar does her own fair use analysis.

On the other side of the spectrum, Felix Salmon blames Silicon Valley’s cult of disruption for GoldieBlox’s behavior. And, hey, are the toys actually any good?

Updates

Update: Last night, on November 26, GoldieBlox marked the original video private and uploaded a new version with modified music and all Beastie Boys references removed. This morning, founder and CEO Debbie Sterling posted this public letter to the Beastie Boys.

December 11: Yesterday, the Beastie Boys filed a countersuit for copyright and trademark infringement. We may see a ruling after all.

March 18, 2014: GoldieBlox settled out of court with the Beastie Boys, agreeing to publicly apologize and pay a percentage of proceeds to STEM education for girls.

In your informed opinion, does it matter that the original “Girls” was satirical? The Goldiblox suit hinges on whether their version is a parody of the song and criticism of the “highly sexist” lyrics, so is that argument weakened if the judge recognizes that the over-the-top sexism in the lyrics is ironic to make a point about the stupidity of sexism? Or would the court have to decide if the average listener would recognize the irony or take it seriously?

Terrific write-up of the analysis, and I say that as an IP attorney.

One thing that I discovered this morning is that back in 2004, the Beastie Boys had a song on a CD that Wired put out in conjunction with Creative Commons. The Beastie Boys’ song was included per the “Noncommercial Sampling Plus” license. The “noncommercial” rules on the Creative Commons website says that a work is “primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or monetary compensation.”

Is the video? Is the Goldieblox video primarily intended for or directed toward commercial advantage or monetary compensation?

There are arguments both ways – the primary intention of the video may very well be to empower girls and young women and a side effect may be to get them to buy the product.

How does this fit in to the situation? Well, it makes it clear that there are certain limited circumstances where the Beasties have used their music in promotion of something, so at least in the last ten years it hasn’t been an absolute bar for them. Whether that has any impact on anything, I can’t even begin to guess. But it is interesting!

Infringement is indeed theft — theft of services. The thing the author does not have is the payment for the infringing usage.

I want to say a little something that’s long overdue

The disrespect to women has to got to be through

To all the mothers and sisters and the wives and friends

I want to offer my love and respect till the end

Adam Yauch, Sure Shot, 1994

My opinion is simply with yours. It feels crass and insensitive. It’s simply not cool. Worse I get the impression by their quick request for a Declaratory Judgement, that they studied the legality very closely in advance. Meanwhile The Beasties already corrected their stance on sexism 20 years ago and the song, 7 years after they wrote the song recounting how teenage boys think.

IMO, brand respect is earned, not legally co-opted.

Also: Amazing post Andy, Thx. And if there was an award for best headline, you’d get that Pulitzer 😉

Great writeup. The only thing I’d add is… did you pay attention to the list of “defendants” in the court filing? It’s quite long, because of all the copyright interest overlaps.

I’ve been thinking that they pre-emptively filed the paperwork and named all those people to force any disputes into a single court case. Otherwise, each party could file a separate case in effort to tie up the toy company’s legal bandwidth and budget, until they beg the court to consolidate. Big evil holding companies do that sort of thing.

w/r/t “This is all a publicity stunt”.

While I wouldn’t draw a straight line from one to the other, this brouhaha reminds me of the recent Cheerios commercial depicting a biracial family (“Cheerios ad with mixed-race family draws racist responses”, http://www.today.com/news/cheerios-ad-mixed-race-family-draws-racist-responses-6C10169988). In both cases you have an ad that starts with a ad that would probably go largely unnoticed if the “campaign” didn’t then draw attention to the ad’s detractors (racists in the case of Cheerios, sexists in the case of Goldieblox. At that point the ad goes viral as progressives promulgating it via social media.

I put “campaign” in scare quotes above because, so far as I know, Cheerios didn’t actively draw attention to the racist comments made on their video. But with Goldieblox, I’m not so sure they aren’t playing to the crowd. In their request for declaratory judgement, they go to great lengths to portray the original song as sexist (“in the lyrics … girls are limited (at best) to household chores, and are presented as useful only to the extent they fulfill the wishes of the male subjects”), and themselves as bastions of equality (“Goldieblox created its parody video specifically to comment on the Beastie Boys song, and to further the company’s goal to break down gender stereotypes and to encourage young girls to engage in activities that challenge their intellect, particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math”). Of course they are abligated to do so if they want the ad to be considered a parody, but the text appears pitched as much toward the GoldieBlox target demographic as it does the legal system

If UpWorthy has taught us anything (aside from The One Thing Wrong With Our School System And Why We Mistrust Teachers), it’s that videos championing progressive cause can become widely distributed on the internet, doubly so if they position themselves as fighting against a bunch of prejudiced yahoos. If a company were to take advantage of this knowledge, the Goldieblox campaign is how I imagine it would look.

Here’s what my wife (who is an attorney– but not a copyright attorney) posted on my FB wall after I linked the story:

(As a note, I don’t understand most of the moon-language in it, either…)

Here is what I put together in my Copyright outline on parody:

Parody has an obvious claim to transformative value. As a form of comment or criticism, parody can provide social benefit by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new work. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. 510 U.S. 569, 579 (1994); Mattel Inc. v. Walking Mountain Productions 353 F.3d 792, 800 (9th Cir. 2003). The threshold question when fair use is raised in defense of parody is whether a parodic character may reasonably be perceived. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music. Inc. 510 U.S. 569, 582 (1994) (The Court did not address the issue of whether an intent to parody is required). The heart of any parody is its evocation of the message of the original work in order to alter that message in a way that humorously expresses the author’s opinion of the original work. See Abilene Music, 2003. The social context of the defendant’s work and the actual context in which the plaintiffs work is placed in the defendant’s work are relevant to the determination of whether the defendant’s works constitutes a parody. See Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, hic. 510 U.s. 569, 588 (1994) (“In parody, as in news reporting, context is everything.”); Mattel Inc. v. Walking Mountain Productions 353 F.3d 792, 802 (9th Cir. 2003) (by depicting Barbie as being harmed by kitchen appliances or in sexually suggestive contexts, defendant photographer was commenting on Barbie’s influence on gender roles and the position of women in society). Abilene Music 2003 (use of only three lines from the original was sufficient to from a basis for a parody because it is not necessary for a parody to devote a certain proportion of its length to the copied material, focus only on the plaintiff’s work, or rely entirely on the plaintiff’s work for its melody or form). The impact of the commercial nature of the parody is lessened or negated by the transformative nature of the parody. See Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 584 (1994) (works involving comment and criticism are generally conducted for profit); Mattel Inc. v. Walking Mountain Productions 353 F.3d 792, 801 (9th Cir. 2003) (extremely transformative nature and parodic character of defendant’s work made its commercial qualities less important).

The parodist is permitted to appropriate enough of the plaintiffs work to “conjure up” the object of the parody. Enough of the original may be taken “to make the object of its critical wit recognizable.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rp Music, Inc. 510 U.S. 569, 588 (1994). The amount taken does not become excessive merely because the portion taken was the heart of the original. Once enough has been taken to assure identification, additional appropriation must be balanced against the extent of the parody, the amount of new material added by the defendant and the likelihood that the parody may serve as a market substitute for the original. But see Mattel Inc. v. Walking Mountain Productions 353 F.3d 792, 804 (9th Cir. 2003) (“We do not require parodic works to take the absolute minimum amount of the copyrighted work possible.”). In the area of parody, there are three considerations to be made in determining whether a taking is excessive under the circumstances: the degree of public recognition of the original work, the ease of conjuring up the original work in the chosen medium, and the focus of the parody. Fisher v. Dees 794 F.2d 432, 439 (9th Cir. 1986) (a song is difficult to parody effectively without exact or near-exact copying). See Mattel Inc. v. Walking Mountain Productioii 353 F.3d 792, 804 (9th Cir. 2003) (copying of Barbie doll was justifiable in light of the medium of photography used by the defendant).

But note, advertising parodies find it more difficult to assert a fair use claim. See Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. v. Miramax Films Corp. 11 F. Supp. 2d 1179, 1187 (C.D. Cal. 1998) (“Advertisements are entitled to less indulgence than other forms of parody.”).

So, I think GoldieBox can make a pretty fair argument that the song they used was a parody in that it evokes the message of the original work in order to alter that message in a way that humorously expresses the author’s opinion of the original work. In the original, the Beastie Boys say:

Girls, to do the dishes

Girls, to clean up my room

Girls, to do the laundry

Girls, and in the bathroom

GoldieBlox can certainly argue that their alterations of the original song express their opinion that girls are capable of much more than cleaning up after boys. The Beastie Boys will have an uphill battle, but, because this spot is more or less an advertisement for GoldieBlox, it is possible that the court will be less inclined to side with GoldieBlox. Either way, it should be an interesting case!

My copyright knowledge extends as far as my memory of many discussions with copyright lawyers over the past 6 or so years.

The most maddening aspect of those discussions was that there is absolutely no way to know, that a huge amount depends on what judge you get, and what mood he/she might be in on a given day. From the actual cases these lawyers were involved in, they determined that it was far safer to attempt parody if it involved humor. Insanely, getting the judge to at least chuckle at your work would go a long way towards having it judged fair use.

Separate from that, though, I also got advised that while it’s not at all stated this way in the law, you often have a better outcome if you emphasize a specific one of the four factors. In my experience, it was strongest to emphasize critique, and along those lines, it was recommended that you are better off more directly making use of as-close-as-possible intellectual property rather than attempting to vaguely disguise it or change it to be less recognizable. That is, if you’re creating a McDonald’s parody that critiques their lack of environmentalism, it is best to use *the* Golden Arches, and not to create a new golden-arch-ish logo.

All of this is to say I’m fully with Andy that it would be great for everyone to have more cases actually fully get decided at the highest level so there is a clearer line, and it is safer for artists to have some idea the risk they are taking on when creating a parody.

Thinking about the Beastie’s own monumental and sample-rich Paul’s Boutique (a “commercial” product also), do you think the band and the Dust Brothers should have poured over the wills of the artists they sampled? I understand the wishes of the dead, but I’m not sure where this fits with respect to the laws.

“[W]hat could be cooler than being sued by the Beatles?” – Mike D http://www.beastiemania.com/songspotlight/show.php?s=soundsofscience

This story seems to similarly fascinate me because it pushes so many buttons, especially along the lines of advertising and art in the digital age. What would Andy Warhol thing? Is Weird Al a pundit now? So many thoughts! This all seems like the kind of business moves people would make if they were brought up on the Beastie Boys. A band that is familiar with daring to be different, getting told to stop what they are doing, shame, cultural appropriation, and admitting to mistakes.

When people point to the original Girls as satire, I note they never played it live ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girls_(Beastie_Boys_song) ) and Licensed to Ill was going to be called “ Don’t Be a Faggot” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Licensed_to_Ill )

Such a great & informative post, Andy—thank you for it!

The sea of armchair lawyering and Tech Smug around who knows more about an interest area of the EFF’s than somebody else, has really bummed me out. A lot.

In the Web 1.0 world, we all helped each other out. Most of the Twitter banter that I’ve observed however, is about how one party is more or less right to sue the other—on what legal basis—that it’s the loser’s fault for not knowing Fair Use inside and out—etc. And that sucks. It’s no different than girls bullying each other over jealousy issues.

My first thought when I heard about this, was that the whole thing sucked. Two of my favorite entities there are: how could one have wronged the other? There has to be a mistake here.

Then I had the thought, that maybe instead of Yet Another Lawsuit as the outcome of this, how cool would it be if the Beasties and Goldieblox could come together to evangelize Fair Use to the masses? Of course, that was an idea made on the assumption that Goldiblox CEO/Founder Debra Sterling was just an innocently clueless engineer in unfamiliar waters. Knowing now that she’s done work in brand and marketing, I doubt the latter.

The core idea, I still stand behind though: because everyone is now making YouTube videos and the creative landscape has become so ‘democratized’ by online tools, isn’t it time the Techies step off the Smug Soapbox and make an effort to evangelize Fair Use best practices to the masses?

Barbara Mandrell did this with with seat-belt safety, after a major car accident in which her seat belt saved her life. American awareness and use of seat-belts, rose dramatically. Now, it’s rarely questioned and just habit for most folks (which is VERY unlike seat-belt use in the 1970s).

Likewise, Mothers Against Drunk Driving was formed by a woman whose son was killed in an accident. All these fussy details about blood alcohol level, the difference between being ‘buzzed’ versus ‘wasted’ and how much alcohol per one’s body-weight, etc? That’s all in our common vernacular today, but 30 years ago? No way!

Goldieblox has every opportunity to do the right thing and make good on a bad judgement, by picking-up the baton on evangelism for this. In fact, MCA would probably be smiling down from heaven in approval, as a formerly rowdy bad-boy gone Buddhist/Feminist peacenik, were Goldieblox to to this.

Anything to honor MCA. C’mon ladies, let’s step it up and do this!

Just a reminder: trollish anonymous comments will be deleted. If you can’t keep it civil, at least put your name on your words.

Great post. For the fun of it, you may be interested in this perspective on the lawsuit from Etsy’s lawyer. Yes, the legal rap rhymes.

To the extent that “infringement is theft of services” is a coherent argument (it isn’t, as a a recording is not a service) the four factor test covers this. The Goldiblocks parody has no possible effect on the market for a misogynistic 80s rap song. Nobody is going to listen to it instead of buying the original.

I’d like to point out that there is one other issue that hasn’t been mentioned nearly as much, and that is the use of the Beastie Boys’ name in the title, thereby implying that they were part of the process.

I clicked the link to the video originally because I knew of both the Beastie Boy sand GoldieBlox, so thought it was cool they were working together. However, they did not work together on this.

This puts them (BB) in a tough situation that is invariably going to damage their name.

Rob Myers: You do know there are recording artists who offer the writing and recording of jingles as a service, do you not?

Mr. Baio;

Your “commercial example”, above, actually makes the same point I’ve been making in other venues – the infringing work you cite (Naked Gun 33 1/2) is another artistic work, itself a parody – whether commercial or not. Using a parody of an image in the promotion of a work that in-and-of-itself is a parody is an appropriate expressive use. *Every* case cited to justify “Fair Use” (which we agree is rightly much more supported now) is a case concerning creation of an expressive work – be it music, video, criticism, journalism, etc.

The distinction of the case in point (GoldieBlox) is that it is not an expressive work in-an-of-itself – whether to be sold commercially or not. Neither is it a commercial advertisement for an expressive work – such as the movie you cite.

While a motivation of the creators of the underlying product is a social goal (and not all who share the social goal believe this product serves that goal), it is nevertheless purposed to sell an unrelated product – in fact this exact video is a candidate to win an advertising slot during the Super Bowl broadcast. The product being sold is *not* a social commentary, nor artistic work, nor act of criticism, nor piece of journalism – it is a toy, to be sold to parents, through retail (online and physical) outlets.

I have yet to see a single case presented where the “Fair Use” exception is used for commercial advertisement for an unrelated physical product. Other examples have been given above (“Shout” for the cleaning product, e.g.).

The confluence of releasing this advertisement on YouTube, the “new” sharing economy, sampling/re-purposing as an art form, the (much-welcomed) rise of strong women creating product to bring better opportunities to young girls – all of these seem to serve to obfuscate the underlying point – while in the form of a parody, this nevertheless is just a commercial advertisement to create sales of a physical product.

Tracy Hall

Tracy: Thanks for commenting. I don’t see why an advertisement for a toy would be significantly different than a film in the eyes of the court, but just for the heck of it, I have another example that fits your criteria, and Leslie Nielsen is again at the center of it.

If you’re old enough, you may remember those goofy Energizer Bunny commercials, where the battery company made award-winning spoof commercials and then marched their drum-banging bunny through them.

Coors decided to parody the commercials by having Leslie Nielsen dress as the Energizer Bunny and march through its beer commercials. Eveready, the owner of Energizer, sued for copyright infringement, trademark infringement, and trademark dilution.

In Eveready v. Coors, the District Court ruled that it was fair use, writing, “Although the primary purpose of most television commercials may be to increase product sales and thereby increase income, it is not readily apparent that they are therefore devoid of any artistic merit or entertainment value.”

A commercial advertisement that parodied a creative work against the rightsholder’s wishes, to sell an unrelated physical product, found fair use.

Now, this was before the 2 Live Crew case, which further shifted the balance towards allowing commercial use. But who’s to say? Fair use is a test, and each one is judged on a case-by-case basis.

Maybe Goldieblox will win, maybe Beastie Boys will win. We don’t know if it’s fair use, and we won’t until a judge delivers a ruling.

The only real way to get a straight answer is at the federal level.

What do you mean by a “straight answer”?

A final answer that won’t be changed on appeal? because federal judges are consistent, or because it’s tough to appeal beyond them?

No mention of compulsory licenses?

Since this was recorded from scratch, even if this isn’t any kind of parody or fair use, the Beastie Boys have absolutely no right to stop it, just to demand money at a statutory rate, right?

@Tracy Hall:

The media coverage of the video and its viral spread, before the controversy about the song, speaks to its entertainment value, as well as its message, both of which puts it squarely in the middle of art realm. In addition, the advertised products are unique, well designed toys. They have some art value in themselves, similar to the “Naked Gun” movie, and they would almost certainly enjoy copyright and trademark protections.

I think that if our copyright laws are ever going to change to something more libre (real ownership), individualized artist’s “moral rights” and “end user license agreement” are things that will need to go. While Beastie Boys fans rightly should want to honor MCA, defending the song “Girls” really should be taken with a grain of salt. At best, this well known and popular song is egregiously facetious when it comes to women. I can understand them not liking that the parody is explicitly an advertisement, but it’s hard to really feel any sympathy when they are profiting from a sexist message. I’m sure the Beastie Boys are not hurting from all of the publicity in some kind of zero sums game. Just because I think Lars Ulrich a great musician, if he were to have come to an untimely end in the Napster days does not mean I would suddenly have agreed with his take on copyright. The fact that all of this can be taken so seriously when it comes to a legal standpoint might actually say something about the status quo. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hCimLnIsDA

Douglas: Yeah, that’s the sort of straight answer I was referring to, but I see how that’s confusing. I removed the sentence. Thanks.

As for compulsory licenses, those only apply to cover songs. Changing the lyrics or melody create a derivative work that fall outside of compulsory licensing. In addition, they’d also need synchronization rights to put it to video.

Andy, can I ask a question?

Legality of this aside (which you and I are unlikely to agree on), can we at least agree that appropriating someone else’s artistic work without their permission is a dick move?

Great piece! Probably the most helpful law-related blog I’ve read in a long time. I think the new “Girls” is simply derivative and an excellent criticism of the original song, so it should be protected.

Again, great blog.

@indefensible: In this case? Yes, I agree. Like I said in the post, I think pursuing this case is crass and insensitive, especially in light of MCA’s will and his recent passing. I personally think Goldieblox should have pulled it, or changed the music, once they were aware of the band’s wishes.

But outside of this case, absolutely not. I know fair use doesn’t exist in Australia, but we have a long history of cultural appropriation here that hinges on it, despite its flaws, and there are many, many works of art that should never require permission from the artist.

Virtually everything I love about the Internet involves some level of appropriation without permission. Fan fiction, fan art, mashups, remixes, and parodies are all made without the permission of the original artist. Almost every cover song on YouTube is unlicensed, every gameplay video, every supercut.

Girl Talk, Pogo, Evolution Control Committee, Danger Mouse, Negativland, The Kleptones, Steinski, Kutiman, Eclectic Method. The Beastie Boys. Not dicks.

“First off, infringement is not theft…If Goldieblox stole something, the Beastie Boys wouldn’t have it anymore.”

Linguistic limbo. This is fundamentally no different than if I were to take a clip from Game of Thrones and use it to sell toilets (“Thrones” get it…it’s a parody!). By using something without permission and not paying for it, you reduce the ability of the people who made the original to sell it. (Hey…they got it for free. Why not us?) If you’re taking dollars out of someone’s pocket I call that theft.

I have always hated “Girls.” I became aware of it at a very young age, and it’s message was unambiguously negative at a really impressionable time in my life. I respect that the Beastie Boys distanced themselves from that song, but by that point, the song was already out in the world and being widely misinterpreted. While I really appreciate Adam Yauch’s words in Sure Shot, the iconic status and subsequent cultural impact of “Girls” is not undone with those few lines, satisfying as they are.

Hearing the Goldieblox version scratched an itch I didn’t even know I had, and I admit to being personally biased in this case because of how good it felt to hear lyrics about housework transformed into something empowering. That said, I also respect the Beastie Boys and their decision to have their work not be used for commercial purposes. Their songs are powerful pieces of media that are deeply woven into the cultural consciousness, and I think that they are taking an important stance by having that level of influence and not using it to hawk products and services.

In the end, I am immensely pleased and grateful that the new version of the song exists. However, if Goldieblox has to pay a penalty for that, I will not react with outrage or even surprise. I’m also super curious to see how this will all play out in the courts.

Perhaps what’s key here is that all of the things that you’ve mentioned to be Good are what we consider to be Art (high or low, whatever your fancy).

This particular case involves a business using an artistic group’s work in order to gain exposure and sell their product.

To me, that’s a distinct difference. If the video was created solely to say “Hey, women are structurally discriminated against from a young age” I’d be on your side. But it’s not. And that’s what makes this case smell bad.

For the record, I adore mash-up culture. But I like a *lot* of things that aren’t legal.

@indefensible

I am not Andy, but I thought your point interesting. How often has it been the case that authors or artists did not even want their work revealed, and yet someone (often close friends) expressly went against their wishes to do so. Kafka, if I’m not mistaken, wanted everything destroyed before he passed away; Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger’s private correspondence has been incredibly important for understanding their thought, but was supposed to be destroyed; and Virgil had some similar story with the Aeneid, and Michaelago tried to burn some of his paintings too.

This is not that case, obviously, but there is still a parallel: why does the artist, particularly after they are gone, have the final say on what happens to their work. Once these things are out out into the world, they stop being solely their own (he said, being overly romantic). I’m not saying Goldieblox was in the (moral) right here, but I don’t think I agree that the (moral) wrongness of their action can be determined solely with the artist’s wishes.

Mr. Baio;

and a later case, citing Everyready v. Coors, rules the other way…

http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11078526421590500494&hl=en&as_sdt=2006&as_vis=1&kqfp=16448692370766227519&kql=159&kqpfp=15460181000269190399#kq

The courts will have a joyful time with this one…

Tracy Hall

GoldieBlox didn’t take the audio from the Beastie Boys and used it in their commercial. GoldieBlox created a song which has some relation to the Beastie Boy song. The question is how different the two songs are and if GoldieBox created a new work or not.

A comparison of the two songs, I think the rhythm is the same for parts of the song and the pitches are the same. Everything else in the song is different. I would argue the GoldieBlox song is a completely new song because the instrumentation, vocals and lyrics are different. I would say the GoldieBlox song is inspired by the Beastie Boys song, but inspiration isn’t the same as infringement.

In Canada of course you’d have to rely on different precedents as well as the recent addition of the ability to parody to copyright law, BUT in CANADA you have moral rights over your artistic work and I suspect the intersection of parody and moral rights is a very strange duck indeed. In this case moral rights held by the deceased might be the main form of action.

Of course I don’t know crap all about the law and am just trying to relate it to Canada and UK who have moral rights on top of copyright.

@NoMinorChords By that logic any action that reduces anyone’s potential profit is “theft,” rendering the word practically meaningless. Somebody opens a gas station closer to the freeway than yours? Theft! Walmart sells a product for less than you do? Theft! Burglars break into your warehouse and cart off all your inventory? Same thing!

My point is not to excuse infringement, but that it’s much more useful to draw a distinction between dissimilar activities than it is to conflate them, however morally satisfying the latter may be.

If copyright was still at its original length of 14yr plus an optional 14yr extension, and hadn’t been extended to life of the author plus 70 years, then Girls would be going into the public domain soon and maybe this wouldn’t have been a big issue.

Andy, thanks for the info.

Tangent: People change the lyrics in covers all the time. Do they always ask for permission? Or are innocent changes considered fair game? I suppose that even if no one agrees on what is the “fundamental character” of the work, everyone agrees that you can’t claim a song to be both a cover and a parody.

Just FYI, no, you didn’t remove the sentence.

Another IP Lawyer here — just wanted to say, excellent and accessible write up of the situation.

Your article, as comprehensive as it is, only peripherally touches the issue of the several copyrights involved in music. Specifically, the copyright of the musicians (performance copyright) vs the authors of the lyrics (songwriting copyright). You point out “it is worth noting that the song is performed with original musicians and performance”, without noting how taking a “sample” changes the discussion — and it’s a very important point to every artist who might read your article.

What about the fact that Goldieblox is in the middle of campaigning to get an commercial aired during the Super Bowl through Intuit? Definitely made my ears perk when someone mentioned it as a marketing tactic…

How would this analysis change if the sheet music & lyrics had different origins?

For example – imagine the Beastie Boys had licensed the sheet music from musician ‘A’, and then added the lyrics and created the completed work ‘B’.

So all the parody arguments would only work against the lyrics (work ‘B’) – the underlying music would clearly not be parodied – as it is pretty much identical. So while the ‘Fair Use’ defence would work against the Beastie Boys, the original creator of the sheet music ‘A’ would still be able to sue them successfully.

So could musicians protect themselves by (on paper at least) doing all their works in two steps – Registering the copyright for the work without lyrics as a complete work, and then licensing the music to themselves to create a second work (music + lyrics) for the final work ?

Would there need to be a ‘Chinese Wall’ or a ‘arm’s length transaction’ between the two to be able to use this tactic? Or would simply registering the copyright twice, and ensuring that the sheet music registration pre-dates the completed lyrics+music registration to give it an air of legitimacy ?

NoMinorChords wrote:

“This is fundamentally no different than if I were to take a clip from Game of Thrones and use it to sell toilets (“Thrones” get it…it’s a parody!). By using something without permission and not paying for it, you reduce the ability of the people who made the original to sell it. (Hey…they got it for free. Why not us?) If you’re taking dollars out of someone’s pocket I call that theft.”

You can’t take something that isn’t already there. The dollars aren’t already in the pockets to be removed.

Not giving someone something they are entitled to is wrong, but that doesn’t make it theft.

@Iain K. MacLeod I am not going to spend any time googling and researching to back this up but I do remember reading something years ago that the The Beastie Boys had all the samples cleared on Paul’s Boutique, meaning they paid to use them (I want to say for $125k). Also, if my Beastie knowledge serves me correctly, before they were international superstars an airline company used one of their early punk songs without permission in a commercial. The Beastie Boys sued and won. I was under the impression that they used that money to make “License To Ill” and that is why the album graphics are that of an airplane with a Beastie Boy logo on it.

Also, at the time of “Paul’s” copyright law was very different. Today it would take a lot more money to get all those samples cleared.

This is a fascinating write up that clears up a good amount of distilled information out there.

I’m definitely not a lawyer but it does a good job explaining where the grey areas are in the situation. To me that is all I need.

Thanks!

This is a fascinating write up that clears up a good amount of distilled information out there.

I’m definitely not a lawyer but it does a good job explaining where the grey areas are in the situation. To me that is all I need.

Thanks!

Thank you. This is exactly the article I was hoping to read on this topic.

If it is deemed “fair use”, do the Beastie Boys not get a royalty at all?

In music, aren’t the writing credits for lyrics AND melody? If it is a “new work”, don’t they still get writing credit for the melody–if not the lyrics?

I’ve licensed thousands of songs from the biggest artists in the world for many products, services and films during my career and I’ve attempted to license “Beastie” material. Quite true, they made a decision long ago not to allow their music to be used in advertising for products. Its their right; its their creative and no matter how credible the basis for GoldieBlox’s commercial intent; to level the playing field and inspire young females to consider engineering as a career; even such a worthwhile commercial platform does not convey to them a hall pass (to teach and inspire people) to rip off artists.

Alas, someone gave GoldieBlox really bad advice. I hope and trust the Beastie’s prevail. This is not a parody; its a damn shame. And, what’s with all the noise about the new digital mediums providing a new reason for poaching artists rights? Look, say what you will, music drives the success of a ton of products, brands and services; but ripping off artists; and masking commercial intent… way uncool.

70 years after death is not “an absurdly long time”, it’s a reward to the author and his/her heirs for their creative originality. That statement contradicts the very nature of the copyright laws, to foster creativity in the arts. Why the hell should I create something commercially only to have its worth stolen from me upon my death?

Great, GREAT comments here. Thank you everyone for the insights. I learned a lot. I saw this article on Mashable. http://mashable.com/2013/11/27/goldieblox-pulls-beastie-boys-song/

I can say, I am disappointed that the parody did not remain (personally), but I understand. It was such fun. I hope everyone gets out of this unscathed.

Great article and reminder of the ambiguity of fair use. Some thoughts, from the perspective of a creative.

While it’s easy to assume that this is all a PR stunt, that assumption puts significant weight on the idea that Goldiblox and their creative team has the time and resources to A) specifically identify a song that by itself was already controversial 25 years ago as a lightning rod for controversy B) re-write the lyrics to change them into a form of female empowerment C) concoct an elaborate Rube Goldberg contraption, hire a film crew, cast actresses, shoot the commercial, edit it, and then put on the web as an advertisement for a product that whose intent is to empower young girls, and then sit back and wait for controversy to ensue.

Perhaps a Fortune 500 company with a global agency and a team of lawyers would be able to deliberately take such a risk, but given the low-budget nature of the spot itself I’m more inclined to believe that this is merely a case of a clever startup company taking the cheap and easy route by capitalizing on another artists work for the sake of their own.

What’s worse, they seem to repeatedly make decisions that only highlight their naivite. Indeed, the release of the “new” video (sans Beastie parody song) may be their ultimate admission of guilt. By taking it down they’ve effectively admitted that they made a mistake, or blinked in the face of lawyer fees. Either way what they’ve proven is the degree to which the original relied on the Beastie track to garner views. (Remember that the original video had almost 6 million views before any copyright controversy errupted. Minus that nostalgic hook, the video is clearly just another YouTube commercial with low production value.)

In the end, Goldiblox’s product may be great but the entire situation merely highlights the unfortunate trend that access to cheap filmmaking technology and easy distribution have created the marketplace allusion that everything is free.

Well, we may not get a ruling after all:

http://blog.goldieblox.com/2013/11/our-letter-to-the-beastie-boys/

Well-written overview of the issue. Thank you. I fall into the camp that infringement is a form of theft, but I am a writer, so that colors my opinion. It would be fun though, to go out and steal a bunch of Goldiblox toys, give them to little boys to play with, and call it a parody.

Thanks for the discussion, everyone. Goldieblox pulled down the video, dropped their case, and published an open letter to the Beastie Boys. This story is over, so I’m going to close the thread. Thanks for participating.