Two weeks ago, I wrote about how everyone got the viral Will Smith AI video wrong.

Most people believe that Will Smith’s team used AI to generate fake crowds and fake fans, presumably to cover for low turnouts, but the reality was much more mundane: they used AI to turn real photos into short video clips for a montage. The crowds were real, but everyone was convinced they were fake.

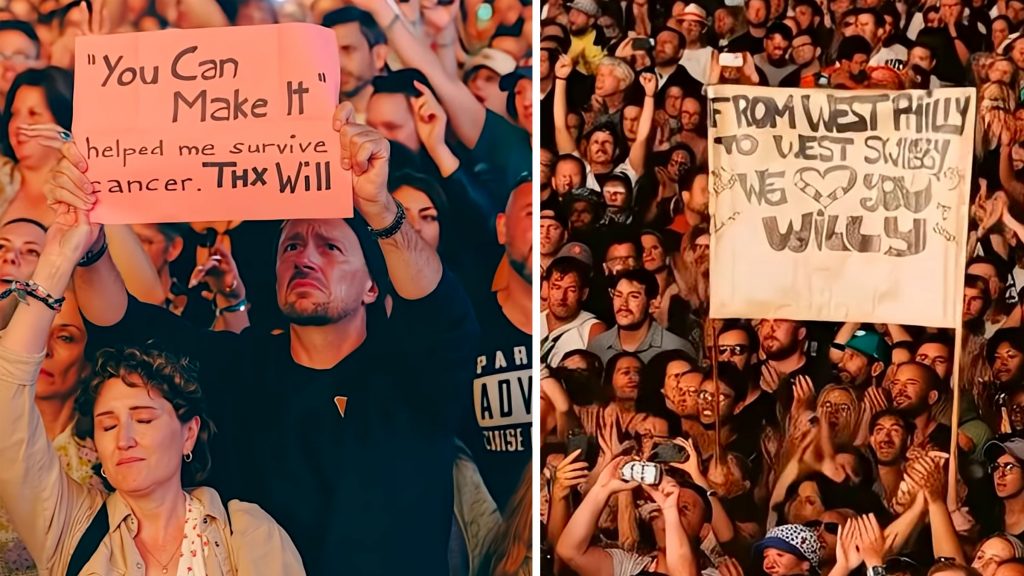

The focus of the internet’s suspicions was a couple holding a sign saying that a Will Smith song helped them to survive cancer, which Futurism called “nightmare fuel” with an expression “never before seen on a living human face.” Redditors called it “pathetic,” “vile,” and “sad and weird.”

After writing my post, I was left wondering what this uniquely-modern experience was like for these two people.

How did it feel to have millions of people think that you didn’t exist and were generated by AI? What was the story behind their sign, and what did that moment mean to them?

So I tracked them down to ask them.

Their names are Patric and Géraldine, and they live in Bern, Switzerland, where the festival was held that they were photographed at. I found Patric through his account on Instagram, and conducted the short interview below over email.

I saw that Will Smith posted on Instagram that he was “deeply moved” on the video posted from Gurtenfestival that you’re both in. I was wondering what that moment was like for both of you, and the story behind the sign. How did “You Can Make It” help your girlfriend in her fight with cancer?

Patric: On July 20, we were blown away when Will Smith posted a video of us on his Instagram and reacted to it. It was a huge moment for my girlfriend—she’s been a big fan of his since childhood. The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air was her favorite show, and as an only child, she always wished she had a big brother like Will.

The song “You Can Make It” got her through her cancer treatment—every time things got tough, the song gave her hope.

With the sign, she just wanted to thank Will for the song and the strength it gave her. At the same time, it was also a message to everyone who is struggling right now: You are not alone. You Can Make It.

Then, something incredible happened during the concert. Will came down to us, and she got to hug him. That hug gave her so much strength and comfort at that moment. As the song played, we stood there, overcome with emotion. Now we know that sometimes the right people see exactly what they need to see at the right time.

How did it feel to see the AI-generated version of you both in the tour video that went viral two weeks ago? Your face is the thumbnail and it’s clearly you, but it does look strange because the video was generated from a still photo.

Honestly, we didn’t even notice at first that the video was created with AI. To us, the moment itself was what mattered, and we were honored that our image was used as the preview image.

We only learned later that the video was generated from a still image using AI. The fact that it reached and touched so many people shows how emotions can be conveyed through new technologies. For us, being part of this moment was simply special.

Unfortunately, some of the press focused almost exclusively on the AI aspect, viewing it negatively instead of recognizing what the video is actually about.

The video is about how music connects people, regardless of their origin, circumstances, or technology. Honestly, we’re saddened by how technical discussions are pushing this into the background.

What was it like to have people convinced that you both aren’t real people, and that you and your sign were generated by AI? It must be strange to have people question your existence like that.

It was crazy to read that some people thought we weren’t real and that the sign was AI-generated.

But we were really there. The sign was real. The emotions were real, too.

Behind that moment lies a personal story with real people, real feelings, and a real background. Sometimes it pays to take a closer look.

Thanks to Patric and Geraldine for sharing their story.

As generative AI is built into every tool we use, it’s going to be increasingly common for artists and brands to use it for basic everyday tasks. It’s easy to imagine creators turning to AI to convert horizontal videos to vertical for TikTok and Reels, or localizing videos with translated lip-synced dialogue.

I’m sure Will Smith’s team felt it would be convenient and harmless to use AI to turn photos from his shows into short video clips for a tour montage.

In practice, it had wide-reaching unanticipated consequences.

The crowds were real, but the videos of them were in an uncanny space between fake and real. To turn still photos into motion, details were added that didn’t exist. Genuine people and signs became distortions of reality.

Using AI made people question whether the crowds existed at all, and led to reputational damage that will take more than a Snopes fact-check to undo. It also had a dehumanizing effect, turning some of Will Smith’s biggest fans into versions of themselves that appeared unreal.

Anyone thinking of taking the shortcuts that these AI tools offer needs to be aware of these risks, and everyone — especially the press — should be very careful assuming what’s real and what’s fake. The grey area between the two is growing every day.