While researching Oscar screeners last month, I stumbled on a remarkable example of online collaboration in China that’s completely undiscovered here. In short, a group of dedicated fans of The Economist newsmagazine are translating each weekly issue cover-to-cover, splitting up the work among a team of volunteers, and redistributing the finished translations as complete PDFs for a Chinese audience.

It reminds me of the scanlation movement, in which groups of fans scan, translate, and redistribute manga into another language. But I’ve never seen it applied to a newspaper or magazine, especially one as high-minded as The Economist.

It’s an impressive example of online collaboration with simple tools, a completely non-commercial effort by volunteers interested in spreading knowledge while improving their English skills. In the process, they’re taking a political risk in translating controversial articles about their homeland behind the Great Firewall.

I can’t read Chinese, but with the help of Google’s translation tools and several Chinese-speaking friends, I think I’ve pieced it together. (If anyone out there knows more, please email or IM me and I’ll add it in.)

How It Works

They call themselves The Eco Team, a group of about 240 passionate Economist fans led by a 39-year-old insurance broker named Shi Yi. The ECO China forum was originally founded in May 2006 by a mysterious character named “nEo,” though he’s no longer involved with the site. On their About Us page, nEo delivers the mission statement:

“Like the forum name says, producing a Chinese version of The Economist is our goal. But we’re still young and immature; very amateur, not professional. So what? Because we are young, we have the fervor, the enthusiasm, the passion. Because we are amateurs, we’ll double our efforts to do our best. As long as we wish, we can be successful and do a good job!”

Every week, in their Weekly Topics forum (translation), a moderator creates a thread linking to every untranslated article from the newest issue on Economist.com. Here’s the list for this week’s issue, published on February 21.

Volunteers choose their stories in the comments, while the moderator keeps track of assignments. As each story’s translated, it’s posted as a new thread in topic-specific forums, like Special Reports or Science & Technology.

Each article weaves together paragraphs of the original text and its translation, while other volunteers suggest their corrections in the comments. The lead editor incorporates all the comments, eventually arriving at a final draft ready for publication.

The Finished Product

While the Eco Team works on translating every article as soon as each issue hits the stands, the Eco PDF Team bundles up finished translations into Eco Weekly, a bi-weekly PDF with two complete issues for forum members to enjoy and share.

Eco Weekly #49 was released only yesterday, encompassing the November 29 and December 6 issues.

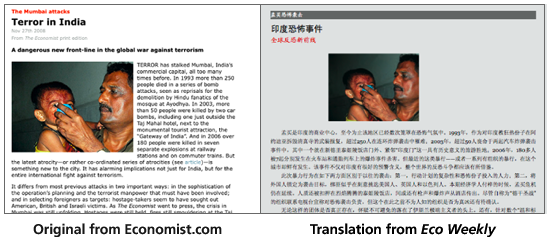

The result is a bit rough around the edges, focusing more on the content than presentation, but perfectly readable. Below is a side-by-side comparison of one article from the issue (view larger).

Only logged-in users can view the PDFs, so I’ve mirrored one below. It’s locked with the password www.ecocn.org, largely so they get credit for their work.

![]() Eco Weekly 2008049.pdf (5 MB)

Eco Weekly 2008049.pdf (5 MB)

Self-Censorship and Political Taboos

But The Economist frequently covers China with a critical eye, leading to frequent clashes with Chinese authorities. In July 2002, an entire issue was banned from the country because of an editorial by Beijing correspondent James Miles, who noted that articles about China are often ripped from the magazine before it hits the newsstands. And there have been reports that access to the Economist website is being disrupted by China’s firewall.

In an interview from 2006, former editor Bill Emmott said, “The Economist would not publish a compromised or censored version of the magazine in order to get into China. However, if the authorities tear out a page of an issue to censor it, we do not then withdraw the whole copy on grounds that it is tainted: as the censorship would be plain to anyone who saw it.”

How do the members of the Eco Team tackle this touchy subject, without risking the entire project? To start, they only translate articles about China in a protected forum that blocks access to search engines and non-members.

Inside, most articles get translated without incident, but there are some exceptions. In a thread explaining why the forum’s protected, a moderator lists some guidelines and some topics that are off-limits:

Along with rapid growth, China is starting to get more influence on the international stage. This can be seen in the international media coverage, with more articles involving China. Since the content of those articles comprises many areas, some topics are prohibited by the Chinese government. To avoid any unnecessary trouble and for the survival of ECO, all comments/articles published in The Economist must abide by the following policy:

There’s one general rule: If the article involves any sensitive topics, if you’re not sure whether it’s permitted or not, please don’t risk any chance by publishing it.

Even though this appears to be severe, people shouldn’t be overly sensitive. In China, not everything related to politics is off-limits. Some issues involving politics can belong in the scope of discussion; for example, discussions on the reform of local government architecture. Articles revolving around these matters are often published in the government newspaper/magazines, it’s not forbidden.

The list of sensitive subjects includes China-Taiwan’s political relationship, Tibet, Falun Gong, the Tiananmen Square protests, the Cultural Revolution, discussions of freedom of the press or freedom of religion (including the “Great Firewall”), and any discussion of the establishment of a new Chinese political party. They note exceptions for the finances and social issues of Tibet or Taiwan, targeting only the political issues.

“Violation of these rules is strictly prohibited. If someone breaks these rules in your forum, don’t allow it,” the moderator writes. “Delete the note right away. If this is the poster’s first offense, give them a warning. If it’s the second offense, delete the ID and block the user!”

As far as I can tell, there’s no political motive behind the Eco Team’s efforts. They simply want to improve their English, while learning about the world around them and pursuing the unbiased truth. But they’re not going to risk the entire project to do it, which makes their moderation guidelines largely defensive. One editor compares it to American political correctness, an attempt to look out for other’s feelings.

Copyright Issues and The Economist’s Stance

I spoke to Shi Yi, the Eco Team’s current leader, and he told me that he has a good relationship with The Economist, including ongoing discussions with executive editor John Micklethwait and the head of their Chinese office. Yi said the Eco Team was granted official permission to do translation in their forum exclusively, since it’s an entirely non-profit and volunteer effort.

The Economist does not approve of the commercial reuse of their translation by third parties. While the Eco Weekly issues are for members only, others have taken their work without permission and syndicated them for commercial use on sites like Blogbus and Ecosky.

Yi mentioned the Eco Forum is funded entirely by donations from an annual fund drive. In the forum’s primary navigation, they also prominently encourage members to purchase a subscription. He also pointed me to the only other similar project he knows of, a Chinese fan translation of TIME Magazine.

I reached out to The Economist several times myself over the past month, but I was unable to get a response. If they respond, I’ll be sure to post a followup.

Special thanks to all the translators that helped with this article, including Ernie, mandroid, usernameguy, mcmjolnir, Melissa, and Secretmuffin.

Update: The New York Times asked me to rework this article for a shorter version in Monday’s print edition. Not surprisingly, the Eco Team translated it into Chinese.

Interesting find. On a side note to this, there is a bit of a risk that a translation is biased in a certain direction, all of a sudden skewing the author’s original opinion (or non-opinion). If that happens — and I don’t know if it happens with this specific project, I’m just generally saying — then local readers may not always understand when they’re reading the original author’s view, and when they’re reading the translators commentary or ommissions. This effect can be particularly strong and problematic if 1) the translators are using the translation job itself to learn the language they’re translating from, 2) we’re entering hotly debated topics like politics and 3) the news article in question becomes quoted all over the web based on that translation. (I’ve had some unfortunate experiences with this, but I’ll spare the details here.)

We’re in your websites, translatin’ your language.

There’s a lot of good web-based, volunteer translation projects happening in China. Two others that I know of are the fan-subbings of US TV dramas, and the translation/subbing of OpenCourseWare materials.

And to Philip above: that’s always been an issue with translation, even with professional translators.

According to my cousin who’s now studying at a university in Guangzhou, tons of his friends in translation departments are paid handsomely by video sharing web sites to do subbings for say US TV dramas within two hours of US air time. In his dorm, a few of those translation students who share the same room name their name “the subbing studio”.

Translation is no easy job, especially for one like Economist, so I just read instead of translate them. I’m very happy that other talented guys would translate them to get more people learn the world in a rather different perspective in plain Chinese.

And it’s not rare to see Chinese version of Eco in another site, sometimes many sites. This is not their problem, it’s everywhere in internet community.

Yeeyan.com is another website that may interest you. Tons of articles were translated in Chinese everyday.

Andy, as some of the other commenters have said, this thing couldn’t be more common in China. More importantly, with censorhip and copyright is so messed up in China and the culture here of ‘mimicry’ to put it lightly guarantees this trend continuing for a long time. I don’t think people take the translation of the economist any more seriously than the other serious translation projects of other magazines, films, tv shows, books, or chatroom discussions (chinese to english). If the work is good, it’s more than likely there is some money involved somewhere, and some people doing proofreading and editing.

Common or not, that’s really quite inspiring. It’s good to know there are dedicated people in China who really do wish to know about how the rest of the world works, and to spread the word, despite the disapprobation.

Translations aren’t rare at all. The way the firewall works everybody who really wants to look at a blocked page can simply use VPN or a simple proxy. The biggest obstacle is the language barrier as you’ve obviously found out.

“Common or not, that’s really quite inspiring” – it’s dopey comments like this that have enabled China’s blatant disregard for intellectual copyright to flourish and diversify. This has absolutely nothing to do with “dedicated people in China who really do wish to know about how the rest of the world works”. C’mon, get real. This is a bunch of people who see an opportunity to make a lot of money in the long term. Wake up, world – you are being taken for a ride. (and do you really believe those Chinese ‘bloggers’ are not being paid to respond to you comments?)

gjb: Do you have any evidence to back that up? It’s pretty clear to me that there’s absolutely no commercial incentive to their participation, and the only money changing hands is from volunteers to keep the site running.

Peter/hsknotes: I never said that translation was uncommon in China (I even mentioned scanlation in the second paragraph), but it’s mostly contained to works of popular culture. It is, however, very unusual for a group of fans to translate an English magazine or newspaper. Unless someone can point me to other examples?

> And to Philip above: that’s always been an issue with

> translation, even with professional translators.

Micah, I’m sure pro translators also face many problems, and subtleties of language can often skew something in different directions. However, I still don’t think that makes these two situations be in the same league. Pro translators typically:

– have incentive to get paid, not incentive to e.g. push an opinion, or whatever incentive they have for doing free translations

– are *not* learning the source language as they go… or you picked a truly, truly bad translation agency

– hand back the translation to you, hence are less responsible for omitting things due to censorship pressure; dealing with that would be your problem then

– often have to react to quality control or customer feedback

– are often assigned to different jobs, thereby somewhat restricting structural bias making it into all of your work

I’m sure you’ll find plenty of exceptions to any of above with pro translators (perhaps they didn’t react to customer feedback, perhaps someone wasn’t very fluent in the language, etc.) but exceptions shouldn’t make you conclude anything… rather you should look at the average and then calculate your risks accordingly. In the past I had the chance to face both situations, pro translations and volunteer teams, and IMO the two situations are very different.

Am I saying volunteer teams don’t do a good job at translations? Nope, not at all. It totally depends on the team and who oversees the effort. You need to ask several questions: is there a structural bias, do people have a good grasp of the source language, is there someone who spot checks quality etc. That is why my above comment was only intended as a sidenote, as it may not be valid for the Economist translators.

Great initiative, but it’s sad to see that they use a bulletin board for something that would be much more powerful as an online collaborative wiki/TM/editor thingie. Community translation is needed for so much stuff – software, websites, movie subtitles, … – but I haven’t seen any good interface for it yet. This cries for version control at least.

Micah: fansubbing is not limited to China. There are dozens of multilingual subtitle sites. And a few subtitle wiki sites, but their interface is ghastly.

Interesting article. Commendable as a community project and as an example of distributed online working, as well as from a political point of view.

Does this mean, then, that I can translate The Economist (or any other book, newspaper or magazine) into Spanish and publish it on my blog, in the interests of spreading the word, and that The Economist won’t take issue with copyright dilemmas?

It would do wonders for my page views, Adsense earnings and language practice (I’m a professional English – Spanish translator).

That kind of attitude by publishers would have huge implications for the translation industry and publisher’s and author’s copyright, which they otherwise seem so intent on enforcing.

Matthew Bennett: No, it’s pretty clear that they’re only looking the other way because the EcoCN is a completely noncommercial project, with no advertisements or revenue. Shi Yi stated the Economist was unhappy with other sites that take the translated articles and run ads with them.

Thanks Andy,

Perhaps I misunderstood that part – I think I understood that users were encouraged to subscribe as members of the forum – but for your average, low Adsense income blogger, what would be the difference between earning 1000€ / year from Adsense and earning 1000€ / year from ‘annual fund drive’ donations?

When you’re relying on donations, you raise only the amount it takes to keep things going. With ads, I think most people would be inclined to pocket the profit as it grows.

But then the guys who run the site could just decide they ‘need’ 2000€ instead of 1000€.

I think the issues you raise in your post are fascinating and relevant across a number of fields. No-one seems to have the answers yet.

If The Economist is happy with this kind of effort, for example, and wish to have this kind of influence in China and/or in Chinese, how do they think this affects their brand and do they believe this kind of community effort is better for their brand/business than having a team of Chinese translators do it professionally?

They could do things like:

ch.economist.com

esp.economist.com

fr.economist.com

etc…

I am so glad to see your passage.

And I’m sorry that my English maybe not so good because I am a Chinese English learner. Unfortunatly it’s also the first time for me to know this kind of team. So I can’t give you more imformations about it. But when it comes to the policy in China, your ideas are quite objective. China is little different from some western countries, but we do wish to know more about the foriegn countries, from the west to the east, from the north to the south. We always have ways to know the world, if we really wanna konw. Although the ways are limitted.

In a developing country,the people’s education maybe so distinguishing.So the views are in great difference. Maybe a Great Firewall can prevent some kinds of unnecessary troubles.It can make this large developing country easier to manage.

These are my points of view.

Andy’s write up of this for the New York Times. Awesome:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/02/business/media/02economist.html

I wrote a paper on the use of wikis in journalism where I mentioned translation as one of the possible advantages. The use of PDF is particularly curious…

@Philipp Like many opensource projects, many fans translations groups are well organized, with different people doing different jobs, and proofreading is a must-have for any fan-based translation groups. That is to say, quality control is taken seriously by the translators themselves.

@Andy As far as I know, many people who joined The Eco Team are from the English departments of prestige universities, many having a decent job and doing this translation as a hobby and as an enthusiast. There is even a dedicated Chinese website and community called Yeeyan that host many such translations. It is a small world now, we do need to learn more from each other.

The Economist’s tolerance for this type of activity is unsurprising. They’re still expanding their circulation (as opposed to American newsmagazines, which are declining). They’re also quite receptive to new forms of distribution, such as the audio edition, “word for word, the articles in this week’s Economist newspaper.”

Their stance on censorship also reflects some cultural differences. They used to be banned in Singapore from time to time. And their UK home market has some of the strictest libel laws in the world. Because they’re used to dealing with restrictions, they don’t have quite the absolutist approach to freedom of the press that you tend to find in the US.

Look — at the end of the day, Spain and most of Latin America are open soci traneties — despite wanna-be autocrats like Chavez, you can openly discuss a wide range of topics.

China is not an open society. The Economist is an explicitly liberal newspaper — not in the American sense of being in favour of the Democratic Party (though they often support it), but in the sense of being in favour of freedom. Freedom of speech, freedom of conviction, freedom to run a business without government interference.

Few publications would give their explicit permission to amateur translators, except for those that believe that principles go before profits. The Economist may be a newspaper that promotes free markets and business, but above all it promotes freedom — and whether its Chinese translators truly realise this or not, it, along with other publications, is opening the minds, hearts and worldviews of the Chinese people.

> The Economist may be a newspaper that promotes

> free markets and business, but above all it

> promotes freedom

Blinkered view from a citizen who regards their society as the only one who is entitled to make pronouncements on what constitutes freedom

Drivel

I have been following your blog for three days now and I should say I am starting to like your post. Now how do I subscribe to your blog?

in a word, i am for those guys who bring us different views outside, chinese need it!

I’m a new fish.so glad to follow this blog.

There are so many prejudices about China.

I’m a Chinese student and I go to the site which is no-profit just for English learning.Some people think too much about the intention.

I come from China .The Chinese people,especially the students and scholars regard The Eco as a good stage to view our country and maybe just learn English~

Once more get myself personally paying way too much time both reading through and commenting i.