Last month, I finally got access to OpenAI’s DALL·E 2 and immediately started exploring the text-to-image AI’s potential for creative shitposting, generating horror after horror: the Eames Lounge Toilet, the Combination Pizza Hut and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, toddler barflies, Albert Einstein inventing jorts, and the can’t-unsee “close up photo of brushing teeth with toothbrush covered with nacho cheese.”

DALL·E 2 diligently hallucinated each image out of noise from the compressed latent space, multi-dimensional patterns discovered in hundreds of millions of captioned images scraped from the internet.

The prompt that finally melted my brain was the one above, with images of slugs getting married at golden hour. I originally specified a “tuxedo and wedding dress” with predictable results, but changing it to “wedding attire” gave the AI the flexibility to depict variations of what slugs might marry in, like headdresses made of cotton balls and honeycomb.

I’ve never felt so conflicted using an emerging technology as DALL·E 2, which feels like borderline magic in what it’s capable of conjuring, but raises so many ethical questions, it’s hard to keep track of them all.

There are the many known issues that OpenAI’s acknowledged and worked to mitigate, like racial or gender biases in its image training set, or the lengths they’ve gone to avoid generating sexual/violent content or recognizable celebrities and trademarked characters.

But it opens profound questions about the ethics of laundering human creativity:

- Is it ethical to train an AI on a huge corpus of copyrighted creative work, without permission or attribution?

- Is it ethical to allow people to generate new work in the styles of the photographers, illustrators, and designers without compensating them?

- Is it ethical to charge money for that service, built on the work of others?

There are basic fundamental questions about whether it’s even legal: these are largely untested waters in copyright law and it seems destined to end up in court. Training deep learning models on copyrighted material may be fair use, but only a judge can decide that. (The fact that OpenAI’s removing some results from the image training set, like celebrity faces and Disney/Marvel characters, suggests they’re well aware of angering the biggest litigants.)

As these models improve, it seems likely to reduce demand in some paid creative services, from stock photography to commissioned illustrations. I empathize with the concerns of artists whose work was silently used to train commercial products in their style, without their consent and with no way to opt-out.

The world was just starting to grapple with the implications of this technology when, on Monday, a company called Stability AI released its Stable Diffusion text-to-image AI publicly.

Stable Diffusion is free, open-source, runs on your own computer, and ships without any of the guardrails and content filters of its predecessors. It comes with a Safety Classifier enabled by default that tries to determine if a generated image is NSFW, but it’s easily disabled.

Unlike existing AI platforms like DALL·E 2 and Midjourney, Stable Diffusion can generate recognizable celebrities, nudity, trademarked characters, or any combination of those. (Try searching Lexica, the newly-launched Stable Diffusion search engine, for example output.)

Releasing an uncensored dream machine into the wild had some predictable results. Two days after its release, Reddit banned three subreddits devoted to NSFW imagery made with Stable Diffusion, presumably because of the rapid influx of AI-generated fake nudes of Emma Watson, Selena Gomez, and many others.

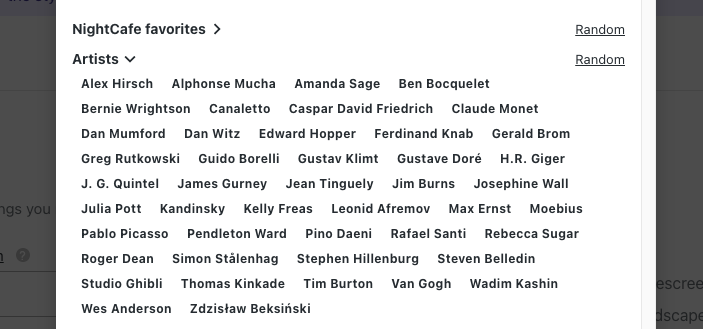

The permissive license on Stable Diffusion allows commercial services to implement its AI model, such as NightCafe, which encourages paying customers to generate art in the styles of living artists like Pendleton Ward, Greg Rutkowski, Amanda Sage, Rebecca Sugar, and Simon Stålenhag, who has spoken out against the practice.

On top of it, Stable Diffusion’s terms state that every image generated with their Dream Studio is effectively public domain, under the CC0 1.0 Public Domain license. They make no claim over the copyright of images generated with the self-hosted Stable Diffusion model. (OpenAI’s terms says that images created with DALL·E 2 are their property, with customers granted a license to use them commercially.)

A common argument I’ve seen is that training AI models is like an artist learning to paint and finding inspiration by looking at other artwork, which feels completely absurd to me. AI models are memorizing the features found in hundreds of millions of images, and producing images on demand at a scale unimaginable for any human—thousands every minute.

The results can be surprising and funny and beautiful, but only because of the vast trove of human creativity it was trained on. Stable Diffusion was trained on LAION-Aesthetic, a 120-million image subset of a 5 billion image crawl of image-text pairs from the web, winnowed down to the most aesthetically attractive images. (OpenAI has been more cagey about its sources.)

There’s no question it takes incredible engineering skill to develop systems to analyze that corpus and generate new images from it, but if any of these systems required permission from artists to use their images, they likely wouldn’t exist.

Stability AI founder Emad Mostaque believes the good of new technology will outweigh the harm. “Humanity is horrible and they use technology in horrible ways, and good ways as well,” Mostaque said in an interview two weeks ago. “I think the benefits far outweigh any negativity and the reality is that people need to get used to these models, because they’re coming one way or another.” He thinks that OpenAI’s attempts to minimize bias and mitigate harm are “paternalistic,” and a sign of distrust of their userbase.

Today we all made the World a more creative, happier and communicative place.

— Emad (@EMostaque) August 22, 2022

More to come in the next few days but I for one can’t wait to see what you all create.

Let’s activate humanity’s potential.

In that interview, Mostaque says that Stability AI and LAION were largely self-funded from his career as a hedge fund manager, and with additional resources, they’ve created a 4,000 A100 cluster with the support of Amazon that “ranks above JUWELS Booster as potentially the tenth fastest supercomputer.”

On Monday, Mostaque wrote that they plan to use those compute resources to expand to other AI-generated media: audio next month, and then 3D and video. I’d expect Stability AI to approach these new models in the same way, with little concern over their potential for misuse by bad actors, and with even less attention spent addressing the concerns of the artists and creators whose work makes them possible.

Like I said, I’m conflicted. I love playing with new technology, and I’m excited about the creative potential of these new tools. I want to feel good about the tools I use.

I don’t trust OpenAI for a bunch of reasons, but at least they seemed to try to do the right thing with their various efforts to reduce bias and potential harm, even if it’s sometimes clumsy.

Stable Diffusion’s approach feels irresponsible by comparison, another example of techno-utopianism unmoored from the reality of the internet’s last 20 years: how an unwavering commitment to ideals of free speech and anti-censorship can be deployed as a convenient excuse not to prevent abuse.

For now, generative AI platforms are some of the most resource-intensive projects in the world, leading to a vanishingly small number of participants with access to vast compute resources. It would be nice if those few companies would act responsibly by, at the very least, providing an opt-out for those who don’t want their work in future training data, finding new ways to help artists that do choose to participate, and following the lead of OpenAI in trying to minimize the potential for harm.

I don’t pretend to know where these things will go: the risks may be overblown and we may be at the start of a massive democratization in the creation of art, or these platforms may make the already-precarious lives of artists harder, while opening up new avenues for deepfakes, misinformation, and online harassment and exploitation. I’d really like to see more of the former, but it won’t happen on its own.

Huh, so there’s nothing an artist can do to get their art out of the AI until it becomes an easier thing to do, and that’s a maybe. And now they’re outsourcing the image collection to third parties, making it hard to make them responsible for the stolen images. Is there anything an artist can do to protect their work from being used?

Not really? They try to filter out watermarked images, so in theory, you could watermark everything you could put online. (Not a great solution, I know.)

The art doesn’t exist in the AI. An AI model is a complex web of math attached to a bunch of words and phrases. It’s actually remarkably similar to the way neurons work in a human brain. During training, an AI gets an image and words that describe the image. It generates some math about the traits of the image (colors, pixel positions relative to edges and other pixels, etc) as related to the keywords. A single image doesn’t do much, because the AI only tracks trends/commonalities. So after seeing a thousand images, it now has a general mathematical understanding of a word like “pastel” or “red” or “flower”.

Again, no part of any original image or art is actually stored in the model. The model is a unique, original collection of statistical/mathematical equations.

I think the only real ethical problem here is reproducing the distinctive styles of living artists. AIs will pick up that a name like “Greg Rutkowski” is associated with a lot of specific traits, so including that phrase in a prompt will trigger equations that steer the results towards those traits… thereby reproducing a “style” on an otherwise unique, original work. That said, “styles” are not something that can be (or should be) copyrighted, which leaves us in a real conundrum for protecting living artists.

Maybe what we need is a way to omit the names of living artists from AI models. How that would be achieved, though… I can’t say.

Whilst its fun to let the machine do the creative work, there is nothing better than being surrounded by brushes and pencils dreaming of the next mark you will make! The act of art making is very personal and is a communication between the artmaker and the image forming… and that experience is very different to watching an ai unfold for you … only put online (stay away from icloud) some of your work, and keep the best ones for yourself and your collectors… there is value for an art collector still in owning the original and only copy!