Yesterday, Meta’s AI Research Team announced Make-A-Video, a “state-of-the-art AI system that generates videos from text.”

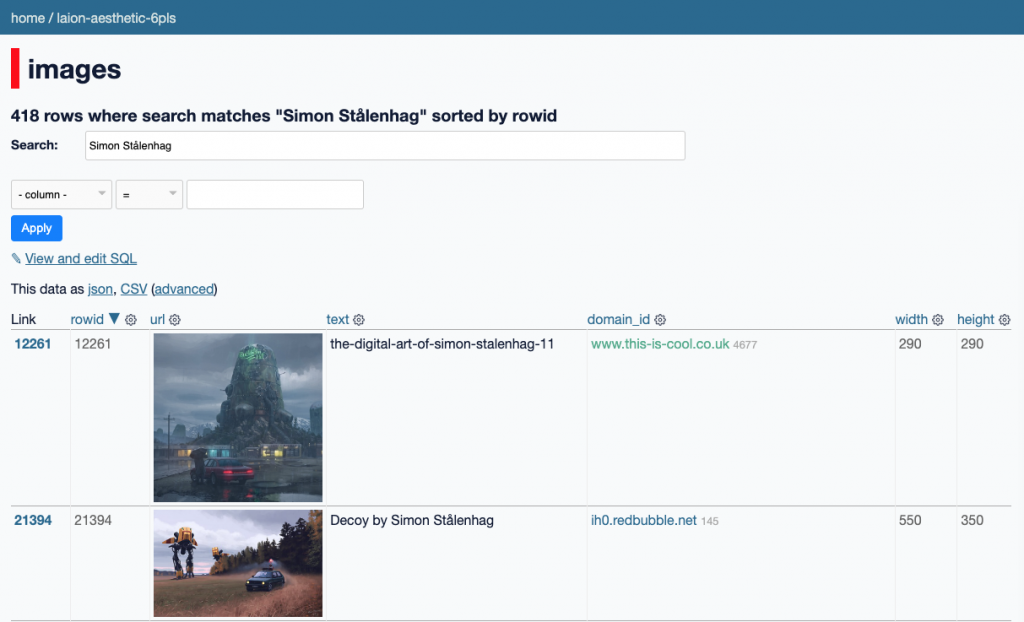

Like he did for the Stable Diffusion data, Simon Willison created a Datasette browser to explore WebVid-10M, one of the two datasets used to train the video generation model, and quickly learned that all 10.7 million video clips were scraped from Shutterstock, watermarks and all.

In addition to the Shutterstock clips, Meta also used 10 million video clips from this 100M video dataset from Microsoft Research Asia. It’s not mentioned on their GitHub, but if you dig into the paper, you learn that every clip came from over 3 million YouTube videos.

So, in addition to a massive chunk of Shutterstock’s video collection, Meta is also using millions of YouTube videos collected by Microsoft to make its text-to-video AI.

Non-Commercial Use

The academic researchers who compiled the Shutterstock dataset acknowledged the copyright implications in their paper, writing, “The use of data collected for this study is authorised via the Intellectual Property Office’s Exceptions to Copyright for Non-Commercial Research and Private Study.”

But then Meta is using those academic non-commercial datasets to train a model, presumably for future commercial use in their products. Weird, right?

Not really. It’s become standard practice for technology companies working with AI to commercially use datasets and models collected and trained by non-commercial research entities like universities or non-profits.

In some cases, they’re directly funding that research.

For example, many people believe that Stability AI created the popular text-to-image AI generator Stable Diffusion, but they funded its development by the Machine Vision & Learning research group at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. In their repo for the project, the LMU researchers thank Stability AI for the “generous compute donation” that made it possible.

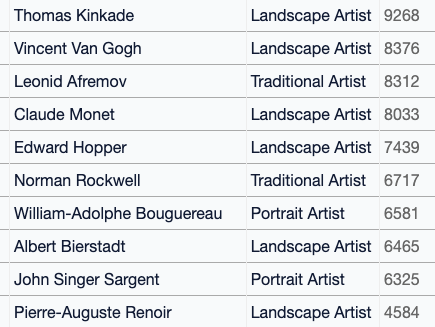

The massive image-text caption datasets used to train Stable Diffusion, Google’s Imagen, and the text-to-image component of Make-A-Video weren’t made by Stability AI either. They all came from LAION, a small nonprofit organization registered in Germany. Stability AI directly funds LAION’s compute resources, as well.

Shifting Accountability

Why does this matter? Outsourcing the heavy lifting of data collection and model training to non-commercial entities allows corporations to avoid accountability and potential legal liability.

It’s currently unclear if training deep learning models on copyrighted material is a form of infringement, but it’s a harder case to make if the data was collected and trained in a non-commercial setting. One of the four factors of the “fair use” exception in U.S. copyright law is the purpose or character of the use. In their Fair Use Index, the U.S. Copyright Office writes:

“Courts look at how the party claiming fair use is using the copyrighted work, and are more likely to find that nonprofit educational and noncommercial uses are fair.”

A federal court could find that the data collection and model training was infringing copyright, but because it was conducted by a university and a nonprofit, falls under fair use.

Meanwhile, a company like Stability AI would be free to commercialize that research in their own DreamStudio product, or however else they choose, taking credit for its success to raise a rumored $100M funding round at a valuation upwards of $1 billion, while shifting any questions around privacy or copyright onto the academic/nonprofit entities they funded.

This academic-to-commercial pipeline abstracts away ownership of data models from their practical applications, a kind of data laundering where vast amounts of information are ingested, manipulated, and frequently relicensed under an open-source license for commercial use.

Unforeseen Consequences

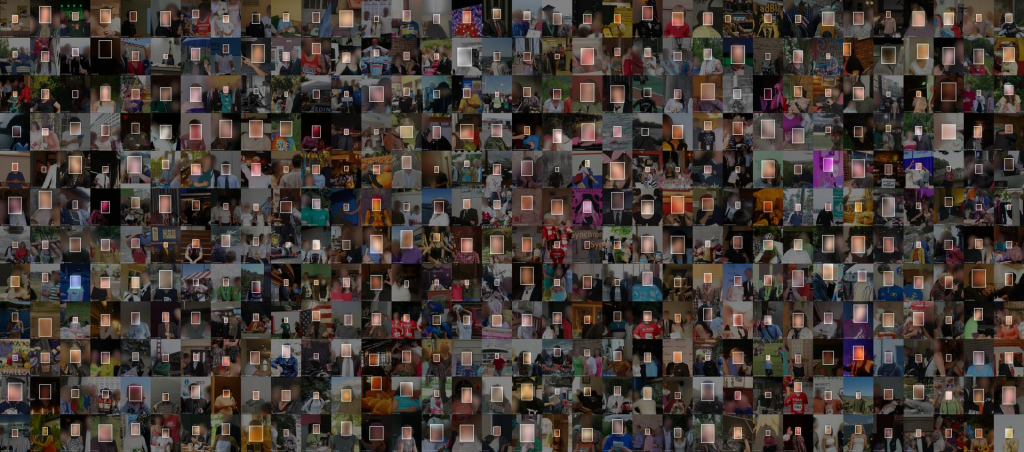

Years ago, like many people, I used to upload my photos to Flickr with a Creative Commons license that required attribution and allowed non-commercial use. Yahoo released a database of 100 million of those Creative Commons-licensed images for academic research, to help the burgeoning field of AI. Researchers at the University of Washington took 3.5 million of the Flickr photos with faces in them, over 670,000 people (including me), and released the MegaFace dataset, part of a research competition sponsored by Google and Intel.

I was happy to let people remix and reuse my photos for non-commercial use with attribution, but that’s not how they were used. Instead, academic researchers took the work of millions of people, stripped it of attribution against its license terms, and redistributed it to thousands of groups, including corporations, military agencies, and law enforcement.

In their analysis for Exposing.ai, Adam Harvey and Jules LaPlace summarized the impact of the project:

[The] MegaFace face recognition dataset exploited the good intentions of Flickr users and the Creative Commons license system to advance facial recognition technologies around the world by companies including Alibaba, Amazon, Google, CyberLink, IntelliVision, N-TechLab (FindFace.pro), Mitsubishi, Orion Star Technology, Philips, Samsung1, SenseTime, Sogou, Tencent, and Vision Semantics to name only a few. According to the press release from the University of Washington, “more than 300 research groups [were] working with MegaFace” as of 2016, including multiple law enforcement agencies.

That dataset was used to build the facial recognition AI models that now power surveillance tech companies like Clearview AI, in use by law enforcement agencies around the world, as well as the U.S. Army. The Chinese government has used it to train their surveillance systems. As the New York Times reported last year:

MegaFace has been downloaded more than 6,000 times by companies and government agencies around the world, according to a New York Times public records request. They included the U.S. defense contractor Northrop Grumman; In-Q-Tel, the investment arm of the Central Intelligence Agency; ByteDance, the parent company of the Chinese social media app TikTok; and the Chinese surveillance company Megvii.

The University of Washington eventually decommissioned the dataset and no longer distributes it. I don’t think any of those researchers, or even the people at Yahoo who decided to release the photos in the first place, ever foresaw how it would later be used.

They were motivated to push AI forward and didn’t consider the possible repercussions. They could have made inclusion into the dataset opt-in, but they didn’t, probably because it would’ve been complicated and the data wouldn’t have been nearly as useful. They could have enforced the license and restricted commercial use of the dataset, but they didn’t, probably because it would have been a lot of work and probably because it would have impacted their funding.

Asking for permission slows technological progress, but it’s hard to take back something you’ve unconditionally released into the world.

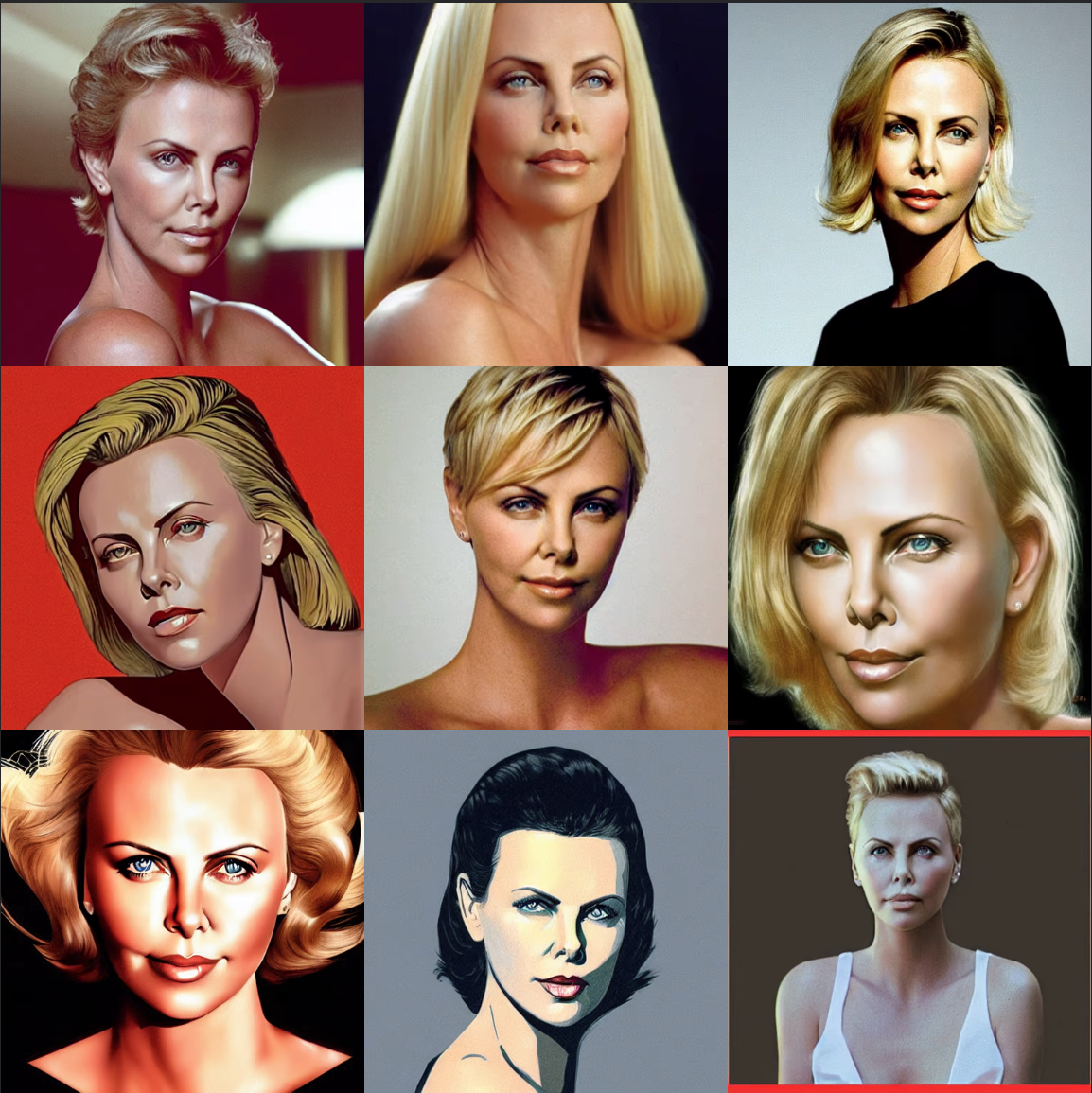

As I wrote about last month, I’m incredibly excited about these new AI art systems. The rate of progress is staggering, with three stunning announcements yesterday alone: aside from Meta’s Make-A-Video, there was also DreamFusion for text-to-3D synthesis and Phenaki, another text-to-video model capable of making long videos with prompts that change over time.

But I grapple with the ethics of how they were made and the lack of consent, attribution, or even an opt-out for their training data. Some are working on this, but I’m skeptical: once a model is trained on something, it’s nearly impossible for it to forget. (At least for now.)

Like with the artists, photographers, and other creators found in the 2.3 billion images that trained Stable Diffusion, I can’t help but wonder how the creators of those 3 million YouTube videos feel about Meta using their work to train their new model.