We all break laws. Every day, millions of people jaywalk, download music, and drive above the speed limit. Some laws are obscure, others are inconvenient, and others are just fun to break.

There are millions of cover songs on YouTube, with around 12,000 new covers uploaded in the last 24 hours. Nearly 40,000 people covered “Rolling in the Deep,” 11,000 took on “Pumped Up Kicks,” 6,000 were inspired by “Somebody That I Used to Know.”

Until recently, all but a sliver were illegal, considered infringement under current copyright law. Nearly all were non-commercial, created out of love by fans of the source material, with no negative impact on the market value of the original.

This is creativity criminalized, quite possibly the most popular creative act that’s against the law.

I don’t think it’s an act of civil disobedience; nobody’s making a statement. Most people don’t know that cover songs need a synchronization license, and even if they did, trying to get one is a confusing and expensive proposition. Unlike the mechanical licenses used to release a cover song on an album, video sync licenses don’t have an affordable flat rate and require the publisher’s explicit permission.

Even as YouTube forges agreements with publishers to handle the synchronization rights for cover songs, it’s nearly impossible for musicians to tell whether their songs are covered or not.

This week, I set out to answer a seemingly simple question: when are YouTube cover songs legal, and how can we do this better?

Conflicting Information

Even trying to determine if a cover song is legal can be confusing for most musicians. There’s no shortage of answers online, but most of them are conflicting. Publishers, musicians, and lawyers all give different answers, none of which are totally accurate. Even YouTube’s own FAQs are incomplete, made inaccurate by recent settlement agreements.

Like any area of copyright law, there’s no shortage of armchair lawyering on blogs and discussion forums about cover songs. A common belief is that cover songs fall under the “fair use” provisions of the Copyright Act, but the question of whether a non-parody cover song could fall under fair use is untested in the courts. Despite this, over 60,000 cover songs on YouTube cite “fair use” in their title or description. (Whether uploaders actually believe that or are preemptively using it as a defense is anyone’s guess.)

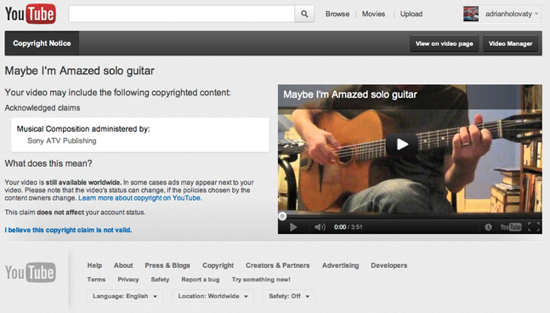

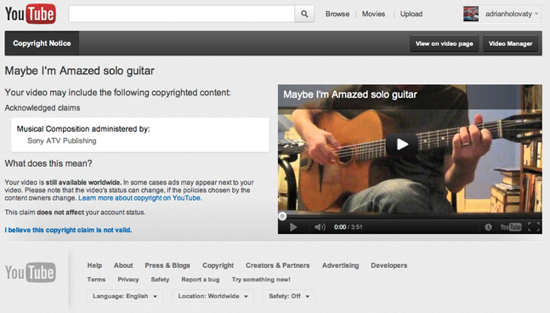

Content ID detects one of Adrian Holovaty’s cover song

While they happily encourage fans to upload covers, YouTube makes it clear that users must have the rights to all content they upload. “We tell users they must own the copyright or have the necessary rights for any content they upload,” said a YouTube representative. “It’s ultimately their responsibility to know whether they possess the rights for a particular piece of content.”

Their only specific guidance for cover songs is in their Copyright FAQ, which says, “Recording a cover version of your favorite song does not necessarily give you the right to upload that recording without permission from the owner of the underlying music.”

But this answer isn’t fully accurate. YouTube’s negotiated blanket synchronization licenses for its users from thousands of publishers, most notably the settlement with the National Music Publishers Association last August. This agreement allowed publishers to opt-in to a program that let them take a cut from a $4 million advance pool and up to 50 percent of the advertising revenue from any cover song they own the rights to.

Frustratingly, we have no idea which publishers have signed on. The NMPA doesn’t publish the list, making it impossible to figure out whether your song is covered by the agreement or not. (I contacted the NMPA, but a spokesperson confirmed that information appeared to be unavailable, but was looking into it.)

Begging for Forgiveness

In reality, the only way to tell whether a song is legal is to risk breaking the law and losing your YouTube account — by uploading the video and waiting for copyright notices.

In the last few months, YouTube has quietly expanded Content ID beyond original recordings to detect cover versions and live performances using the underlying melodies. A YouTube representative confirmed with me, “Content ID’s technology allows us to identify works in an original sound recording, or in a cover version (by identifying the underlying melody of a song), using information provided to us by the publishers.”

YouTube hasn’t talked much about its melody matching technology, but it was in the news recently after a drunk Edmonton man belted “Bohemian Rhapsody” in the back of a police car. After the Content ID identified the song, EMI initially decided to take the video down, but soon changed its mind and authorized it with advertising.

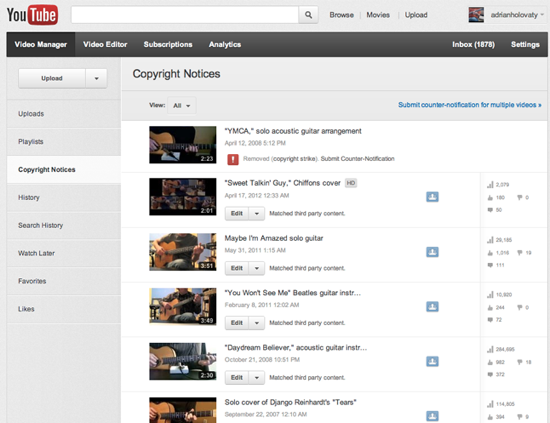

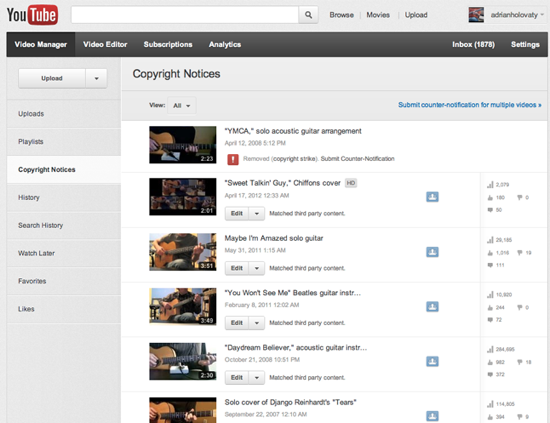

Adrian shared a screenshot of his copyright disputes page.

Everyblock founder Adrian Holovaty is well known on YouTube for his acoustic guitar covers, which have amassed millions of views. I asked him if Content ID identified the melodies in any of his videos. So far, seven of his videos were identified, with all but one rights holder choosing to leave the video online and collect the revenue. Only one video his cover of the Village People’s “YMCA,” was taken down by the songwriter, leaving Adrian with a “copyright strike” on his account. YouTube’s policy allows three strikes before the account is terminated and all videos removed.

The Flaws in the System

The system’s not perfect, though. Unscrupulous individuals are routinely using Content ID to claim content they don’t own to harvest ad dollars from unsuspecting users. For example, two of Adrian Holovaty’s disputed tracks are Django Reinhardt songs from the 1930s, claimed by an obscure company named “Social Media Holdings.”

Other copyright claims may be accidental, as material they don’t actually own finds its way into the Content ID database, like this poor guy who’s received eight consecutive claims from companies claiming to own George Romero’s public domain Night of the Living Dead.

And Content ID isn’t immune to false positives, like the bird calls misidentified as music. Worse, for all these case, disputed Content ID claims bypass the DMCA process for counter-claims entirely, as I wrote about in February.

How can a musician decide what’s legitimate or worth fighting?

Still, YouTube’s Content ID is pushing publishers and rights holders into the modern age. It’s an ingenious approach for an otherwise dysfunctional copyright system that’s too hard for amateurs to navigate, making money for everyone involved while still allowing free creative expression.

The Need for Change

But there’s something strange about this begging-for-forgiveness approach to copyright. It’s like driving without traffic signs, only finding out you broke the law when you’re pulled over.

The real question: Why is it illegal in the first place?

Cover songs on YouTube are, almost universally, non-commercial in nature. They’re created by fans, mostly amateur musicians, with no negative impact on the market value of the original work. (If anything, it increases demand by acting as a free promotional vehicle for the track.)

The best solution is the hardest one: To reform copyright law to legalize the distribution of free, non-commercial cover songs.

Copyright law was intended to foster creativity by making it safe for creators to exclusively capitalize on their work for a limited period of time. Cover songs on YouTube don’t threaten that ability, and may actually prevent new works by chilling talent that could go on to do great things.

As we’ve seen with countless breakout artists from YouTube, budding musicians have built their careers from cover songs that evolved into original material. Karmin, Pomplamoose, Julia Nunes, Greyson Chance…. Even Justin Bieber started with covers of Chris Brown and Nee-Yo before getting discovered.

Now, the next generation of budding pop stars are covering Justin Bieber, with about 216,000 of them so far. It’s all part of the virtuous cycle of culture: We take from it, build on it, and then give back in return. The law should help that along, not hinder it.

Update: I originally published this column over at Wired on May 2. The woman I spoke to at the NMPA confirmed the list of publishers appeared to be unavailable, but promised to look into it. I haven’t heard back, so I followed up again. I’ll update here if I hear anything.)